One of Crossrail’s construction sites has revealed a wealth of history about East London’s industrial past, and the origins of one of its current football clubs.

Although most of Crossrail’s tunnels are deep underground, in places stations and shafts rise to the surface, punching through the archaeological layer, and allowing researchers to study the surface metres for interesting finds.

Such a location looks at the surface to have been just random wasteland but was once the home of London’s largest shipbuilders, and industrial archaeologists have discovered that a lot of the layout and workings of the former shipbuilders can still be found just a few metres below the surface.

That the heritage is still there, and surprisingly deeply buried for a factory site that closed a mere 100 years ago is an unexpected side effect of the DLR — the spoil from its tunnels was dumped on the site, and fortuitously preserving the industrial heritage beneath.

The site is next to Canning Town tube station, and the Lea river, which provided for a convenient site for shipbuilding, originally wood, but later from iron, and it’s the iron-age of the industrial shipbuilding that a new book focuses on.

From the mergers of various smaller firms, the Thames Iron Works and Shipbuilding Company slowly emerged, and for a while dominated the shipbuilding industry in the UK.

However, the move from wood to iron was both to be a boon and a curse, as London’s relative remoteness from the coalfields of the north raised the cost for London shipbuilders compared to the growing shipbuilding industry of the North of England.

While London was losing the battle for cheaper shipbuilding, it won the war for quality, particularly military, where quality often outstrips cost as a determining factor. Many of the UK’s earliest ironclad warships were constructed in London — and many for overseas clients as well.

Made in London was a mark of quality.

The new book goes into the history of the various shipbuilders and their mergers, but also delves into the history of smelting iron — which was, in the early days, also carried out in London.

Although later, iron would be sent to London, often by railway, initially there were iron-smelting facilities in London. Interestingly, there are railways in navy ships, as the iron smelted in London was often improved by adding broken up railway locomotive wheel tires into the mix.

The blend of different grades of iron making London built ships stronger than their rivals.

So good were the shipbuilders that London is where one of the strangest boats ever built was, well, built — the floating tube that was to carry Cleopatra’s Needle from Egypt to London.

Sadly, high quality was not enough to keep the shipbuilder going, and despite a surge in military orders from the Royal Navy, the company was in decline by the turn of the century, and in 1912 it closed.

Curiously, considering the site is currently occupied by Crossrail, the former shipyard was bought by a railway company for use as a depot and sidings.

The book, published by the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) and written by Daniel Harrison spends the remaining section looking at some of the social histories of the industrial site.

The book, published by the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) and written by Daniel Harrison spends the remaining section looking at some of the social histories of the industrial site.

So vast was the industrial site that it was the mainstay of the local economy, which as industrial towns later learnt to their cost, meant a downturn could have devastating effects on the community.

Although the final owner of the shipyard was considered to be liberal-minded, by the standards of the time, he was much hated for how he strove to break strikes by the workers. Surrounding the industrial site with high walls made it very easy for the owners to simply lock people out of work if they wanted, and this caused bitter divides to form.

No work, no pay, was the mantra, and woe betides anyone who upset the management.

Then again, the owner, Arnold Hill spent heavily on social and educational amenities, although the book notes that he sometimes seemed to despair of the worker’s seeming disinterest in high culture and learning, maybe not appreciating that a 48-hour working week of hard manual labour didn’t leave much energy for leisure activities.

The opera society might not have been that popular, but one social club was to leave a lasting legacy — West Ham football club can trace its existence to this very shipyard. Indeed, the football club’s coat of arms is two crossed hammers, after the hammers used to smash rivets on the ships.

Social amenities aside, the reality of grinding poverty and a dependence on a single employer left the local economy dangerously exposed to downturns. A tall flagpole visible over the high walls was watched carefully, for a flag hoisted up meant an order won, work for shipbuilders, and income for local shops.

The collapse of the shipyard was to see the area population shrink even as the rest of London grew. The land given over to railways, and later with the decline of rail freight, abandoned, then used as dumping ground for DLR tunnel spoil.

And now it’s an industrial site once more, although as a construction site with two massive shafts dug down to allow access to the Crossrail tunnels.

The site is now working to support commuters to modern offices, but found by the archaeologists may be the remains of an early commute to work, in an upturned boat of the sort often used to ferry workers across the river.

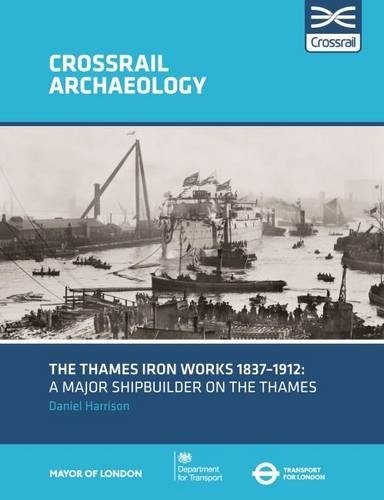

The book, The Thames Iron Works 1837–1912: A major shipbuilder on the Thames costs just £10.

While in places may be a bit laboured, especially in the detailing of the various shipbuilding companies, it contains a wealth of modern and historical photos and is a fascinating insight into an aspect of East London’s industrial and social history.

—

A full series of 10 books will be published by Crossrail/MOLA over the next 18 months, and will explore a wide range of periods and locations, including: Historic buildings along the route; Railway heritage; the development of Soho and the West End; the Crosse & Blackwell factory at Tottenham Court Road; the investigations at Charterhouse Square at Farringdon; Pre-historic east London; and the Roman and Post-Medieval remains at Liverpool Street.

The books will be supplemented by the release of Crossrail’s Fieldwork Reports – extensive technical papers that provide a much greater level of detail and further information on the excavations and their findings.

The Fieldwork Reports are available on Crossrail’s Learning Legacy website.