While tunnel affectionados will be familiar with the “Mail Rail” that runs under London, fewer know that it was in fact the second such system, and an earlier tunnel had been built to carry mail from the Post Office’s national sorting centre – by today’s St Pauls tube station – up to Euston Station.

Alas, a financial failure, most of the tunnel still lies under London undisturbed save for the occasional intrusion by modern subterranean mechanical moles.

For me, learning about the tunnel was indirectly responsible for my ongoing, infrequent research of the Waterloo and Whitehall Pneumatic Railway – as part of that, I came across an article in The Windsor Magazine of April 1900. I managed to find a copy, only to find that the bit I wanted was just a single short paragraph – a problem that often afflicts my research, but in buying it I learnt of an attempt to resurrect that older mail rail tunnel and return it back into use.

The attempt failed – but the story is fascinating, and I transcribe it below for your enjoyment:

(all the images are linked to larger versions)

LONDON’S LOST TUNNEL

£175,000 WORTH BURRIED FOR THIRTY YEARS

By Harry Thompson

Is there any other city in the wide world where a cast-iron tunnel, 2¾ miles in length, could lie disused, unknown, lost to the sensory of all but a few scientists, for over thirty years, excepting London? I doubt it. For this commercial hub of the universe spins onward at such a rapid rate, that the doings of yesterday are already shrouded in mist, and those of a decade back buried as deeply as if the dust of centuries, not years, lay upon them.

Is there any other city in the wide world where a cast-iron tunnel, 2¾ miles in length, could lie disused, unknown, lost to the sensory of all but a few scientists, for over thirty years, excepting London? I doubt it. For this commercial hub of the universe spins onward at such a rapid rate, that the doings of yesterday are already shrouded in mist, and those of a decade back buried as deeply as if the dust of centuries, not years, lay upon them.

So it is that, under the hurrying feet of millions, even echoing their tramp through the heart of the great city, for long years has lain this almost imperishable testimony to the enterprise, courage, and, alas ! mismanagement, of certain of its citizens of the “Sixties.” Expert engineers have examined the tunnel and proclaimed it to be composed of the very best metal “cast-iron such as is not turned out today” to quote the words of a prominent expert and but little affected by earth, moisture, or disuse, for all its lengthy interment and neglect. Representing as it does the burial of close on £200,000, is it not simply marvelous that no effort until the present has been made to rescue this valuable property from the fungi and huge, whiskered rats, and turn it to some profitable utility? The answer is that the tunnel had been forgotten, simply lost, and the man who “found” it found a gold-mine extending from the G.P.O. at St. Martin’s-le-Grand to Euston Station. Should the sanguine hopes of the discoverer be realized and they are based on the reports of the leading authorities he has ” struck” a payable”lead” that is not likely to be “worked out” until flying machines are as ubiquitous and numerous as hansoms in London streets.

Mr. George Threlfall, a consulting engineer, of 50 Fenchurch Street, “found” the tunnel, and the story of his discovery is one of surmounting almost interminable Alps-of-obstacles, and a period of five years occupied with continual struggle before success crowned his efforts.

Mr. George Threlfall, a consulting engineer, of 50 Fenchurch Street, “found” the tunnel, and the story of his discovery is one of surmounting almost interminable Alps-of-obstacles, and a period of five years occupied with continual struggle before success crowned his efforts.

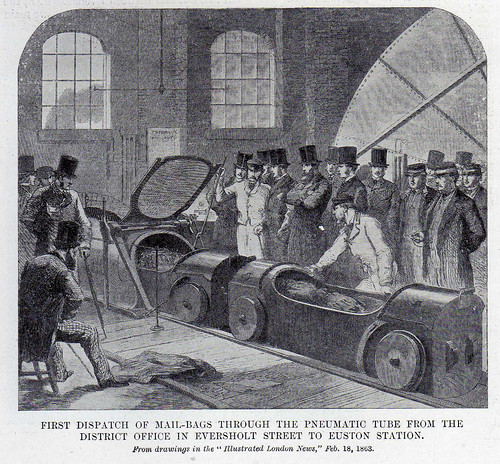

The memorable year of 1863 welcomed the abolition of slavery in America, shuddered at the fierce fighting of kin against kin in the Battle of Gettysburg, grieved at the death-beds of three memorable men Thackeray, Stonewall Jackson, and General Sir James Outram-and showered sunshine and good wishes on the marriage of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales.

It saw also the opening of the Pneumatic Dispatch Company’s first section of the tube that later, starting from Eversholt P.O., N.W., passed down Seymour Street under the Euston Station, along Drummond Street, turning into Hampstead Road, and continuing the length of Tottenham Court Road until New Oxford Street was reached, under which it ran, and under Holborn plunging deeply down the Viaduct, passing below Farringdon Street, shooting up into Newgate Street, and finally reaching home in the old G.P.O. buildings on the corner nearer Cheapside. The tube, which measures four feet in height by four and a half in width, was erected to carry the mails and postal parcels between the two terminal points and wayside offices by means of pneumatic pressure.

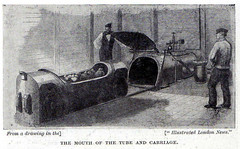

A lad with a pea-shooter utilizes pneumatic pressure in propelling his stinging pellets by introducing a force of air behind them; in an inverse manner liquids are imbibed thorough a straw by sucking the air out, when the interior liquid, thus relieved from pressure, is forced by the weight of the atmosphere on the outside liquid up through the straw. Both these forms of pneumatic pressure were utilized to drive the loaded cars of the Dispatch Company thorough the tunnel. The car ends fitted the tunnel to within an inch all round. The intervening space was closed so as to be perfectly air-tight by a flange of stout india rubber, which clung tightly to tile tube’s interior.

A lad with a pea-shooter utilizes pneumatic pressure in propelling his stinging pellets by introducing a force of air behind them; in an inverse manner liquids are imbibed thorough a straw by sucking the air out, when the interior liquid, thus relieved from pressure, is forced by the weight of the atmosphere on the outside liquid up through the straw. Both these forms of pneumatic pressure were utilized to drive the loaded cars of the Dispatch Company thorough the tunnel. The car ends fitted the tunnel to within an inch all round. The intervening space was closed so as to be perfectly air-tight by a flange of stout india rubber, which clung tightly to tile tube’s interior.

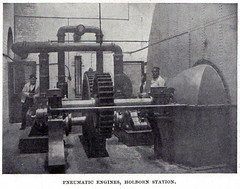

The air was sucked out from in front of a train of cars by an ingenious mechanical arrangement. Two discs of wrought-iron, twenty-one feet in diameter, were screwed on to the sides of an iron wheel having sixteen spokes. Between these two discs, and separated from them, stood a third disc of a corresponding size. Thus this cumbers some wheel, complete, contained thirty-two V-shaped cavities. Briefly, it may be said that the revolution of these cavities at a great speed, before huge bell-mouthed pipes, drew by centrifugal force the air out of the tunnel along which the cars, drawn by suction, sped at a rate of thirty-five miler per hour.

The tunnel as it stands to-day is made up of cast-iron sections in nine feet lengths and nearly an inch in thickness. Each section was cast in one piece, and in shape resembles a “D” lying on its back, with a groove in the corners along which the rails are laid. At the stations hermetically sealed spring doors excluded the entrance of air, so that when necessary a vacuum could be produced before the departing cars. The addition of an engine to revolve the hollow wheel I have described completed the whole outfit of a scheme that was to revolutionise the prevailing forms of carriage and general motion. In a Times leader of February 10th, 1863, I have found the following: “Between the pneumatic dispatch and the subterranean railway the days ought to be fast approaching when the ponderous goods vans which now ply between station and station shall disappear for ever from the streets of London”

The tunnel as it stands to-day is made up of cast-iron sections in nine feet lengths and nearly an inch in thickness. Each section was cast in one piece, and in shape resembles a “D” lying on its back, with a groove in the corners along which the rails are laid. At the stations hermetically sealed spring doors excluded the entrance of air, so that when necessary a vacuum could be produced before the departing cars. The addition of an engine to revolve the hollow wheel I have described completed the whole outfit of a scheme that was to revolutionise the prevailing forms of carriage and general motion. In a Times leader of February 10th, 1863, I have found the following: “Between the pneumatic dispatch and the subterranean railway the days ought to be fast approaching when the ponderous goods vans which now ply between station and station shall disappear for ever from the streets of London”

Over thirty-six years have passed, and the railway van is to-day more ponderous, ten times more numerous and a hundred times greater danger to those who use the streets.

And yet we boast of our progress! Nevertheless, the journalists of those days revelled in dreams of pneumatic enthusiasm; and schemes , that doubtless then appeared well controlled and feasible, to-day are known to have been of the wildest and most improbable. Listen to the exultation-cum-wailing of the Seven Days Journey, a propos of the Pneumatic Dispatch Company, under date December 13th 1862: “We are fast making London a marvelous and unequalled city; and if with-all-our improvements and inventions we could only devise some means of rendering the three millions of dwellers in it safe from the murderous attacks of garrotters and , burglars we should have just reason to be proud of our smoke-covered, but unmatched, capital.”

And yet we boast of our progress! Nevertheless, the journalists of those days revelled in dreams of pneumatic enthusiasm; and schemes , that doubtless then appeared well controlled and feasible, to-day are known to have been of the wildest and most improbable. Listen to the exultation-cum-wailing of the Seven Days Journey, a propos of the Pneumatic Dispatch Company, under date December 13th 1862: “We are fast making London a marvelous and unequalled city; and if with-all-our improvements and inventions we could only devise some means of rendering the three millions of dwellers in it safe from the murderous attacks of garrotters and , burglars we should have just reason to be proud of our smoke-covered, but unmatched, capital.”

Well, the smoke is still with us in greater volume than of old; but the many-tailed cat has tamed the murderous thief and the Pneumatic Dispatch Company, has been resurrected and is promised a new life with electricity for its vital power.

Yet another reference to “olden times,” and the dead past must give way to the living present. The London Journal, in 1863, printed this piquant paragraph: “Not only have letters and parcels been transmitted, through the tube but we hear also that a lady, whose courage or rashness – we know not which to call it – astonished all spectators, was actually shot the whole length of the tube, crinoline and all, without injury to person or petticoat.” Following on this came a multitude of proposals for pneumatic passenger traction. A trial railway was laid at the Crystal Palace, and proved successful. The Waterloo to Whitehall Pneumatic Railway Company was formed. Great Scotland Yard was fixed upon as a site for one terminal station, and adjoining the Waterloo Station in York Road the other. Excavating and tunneling were commenced. The river was to be crossed in an iron tunnel resting in a dredged channel across its bed. The Illustrated Times of August 17th, 1862 gave a full-sized plate, showing the works in progress, and in accompanying letterpress chimed that, “in its present form, the pneumatic system is simply an adaptation of the process of sailing to railways, the wind being produced by steam-power and confined within the limits of a tube.” Passengers were to have perfect ventilation, no smoke (excepting tobacco), no steam, no jolting, no vibration, no collisions and in fact none of the disadvantages more or less attendant on any railway line in kingdom to-day. Although Messrs. T. Brassey and Co. were the contractors for this ideally perfect railway line I cannot say where it has disappeared to. Evidently it savoured too much of Elysium to be allowed to remain on earthly shores.

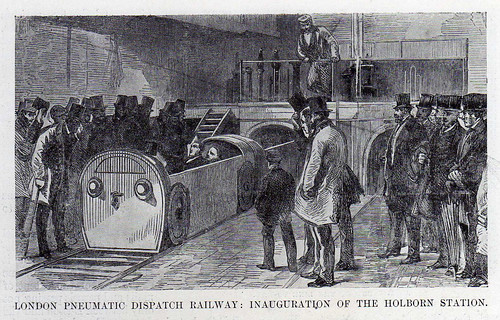

Many persons, however, made the journey in the Pneumatic Dispatch Company’s cars. The Evening Standard of April 5th 1868, mentions “Prince Napoleon and his secretary” as being among the passengers, and an illustration on page 623 [image below] shows, the Holborn Station – which was located in close proximity to the present Royal Music Hall – with a departing car passenger-loaded. For this plate I am indebted to Mr. T. E. Gatehouse, responsible editor of the Electrical Review, Fellow of the Royal Society, Edinburgh, a member of the various Institutions of Engineers, Civil Mechanical, and Electrical, besides being a well-known amateur violinist. Mr. Gatehouse entered the service of the Pneumatic Dispatch Company in 1869 – the days of his fallow youth – and scores of times made the journey through the tube lying in the fast- flying cars. “The central station was in High Holborn,” he states, “and contained the whole of the motive power. Here the, cars changed from one set of rails to another and the time taken in completing the whole journey from end to end was nine minutes. It was always an exhilarating journey, the air being fresh and cool even on the hottest of summer days. From Holborn Circus where the tube dives clown a steep declivity under Farringdon Street, the speed was about sixty miles an hour, and in the darkness it felt as if I were sliding down a hill feet foremost.

Many persons, however, made the journey in the Pneumatic Dispatch Company’s cars. The Evening Standard of April 5th 1868, mentions “Prince Napoleon and his secretary” as being among the passengers, and an illustration on page 623 [image below] shows, the Holborn Station – which was located in close proximity to the present Royal Music Hall – with a departing car passenger-loaded. For this plate I am indebted to Mr. T. E. Gatehouse, responsible editor of the Electrical Review, Fellow of the Royal Society, Edinburgh, a member of the various Institutions of Engineers, Civil Mechanical, and Electrical, besides being a well-known amateur violinist. Mr. Gatehouse entered the service of the Pneumatic Dispatch Company in 1869 – the days of his fallow youth – and scores of times made the journey through the tube lying in the fast- flying cars. “The central station was in High Holborn,” he states, “and contained the whole of the motive power. Here the, cars changed from one set of rails to another and the time taken in completing the whole journey from end to end was nine minutes. It was always an exhilarating journey, the air being fresh and cool even on the hottest of summer days. From Holborn Circus where the tube dives clown a steep declivity under Farringdon Street, the speed was about sixty miles an hour, and in the darkness it felt as if I were sliding down a hill feet foremost.

The impetus of this rush would carry the car up the incline to Newgate Street. To me, who made the trip for the first time, there was something weird and uncanny in being shot through a tube at a high rate of speed, so near the surface of the roadway that the clatter of hoofs and the rumble of vehicles could be distinctly heard, accentuated frequently by the tallow candle or oil lamp being extinguished by the draught. I got so accustomed to the journey that I could tell what corner I was turning. and the streets above precisely at any moment.”

The impetus of this rush would carry the car up the incline to Newgate Street. To me, who made the trip for the first time, there was something weird and uncanny in being shot through a tube at a high rate of speed, so near the surface of the roadway that the clatter of hoofs and the rumble of vehicles could be distinctly heard, accentuated frequently by the tallow candle or oil lamp being extinguished by the draught. I got so accustomed to the journey that I could tell what corner I was turning. and the streets above precisely at any moment.”

After a period of eight or ten years the Pneumatic Dispatch Company relinquished operations. At intermittent times only had the line been worked; and quietly, without fuss or flurry, as became the collapse of a gigantic scheme, the end came and pneumatic propulsion on a wholesale scale received its death-blow in the minds of experts. The insuperable difficulty lay apparently in the impossibility of rendering the tunnel sufficiently airtight. Leakages of various extents prohibited the creating of a working vacuum, and after the engine-power had been increased until it attained six times its original strength, further efforts were considered useless.

After a period of eight or ten years the Pneumatic Dispatch Company relinquished operations. At intermittent times only had the line been worked; and quietly, without fuss or flurry, as became the collapse of a gigantic scheme, the end came and pneumatic propulsion on a wholesale scale received its death-blow in the minds of experts. The insuperable difficulty lay apparently in the impossibility of rendering the tunnel sufficiently airtight. Leakages of various extents prohibited the creating of a working vacuum, and after the engine-power had been increased until it attained six times its original strength, further efforts were considered useless.

The Company had been an extremely powerful one, with rights and privileges guaranteed to it by special Acts of Parliament. Among the directors were the Marquis Of Chandos, the Hon. W. Napier, Sir Charles J. H. Rich, Bart., Messrs. W. H. Smith, Thomas Brassy, and others. Mr. John Aird was the contractor for the line, of which Messrs. T.W. Rammell and J. Latimer Clarke were the joint engineers.

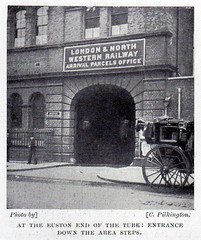

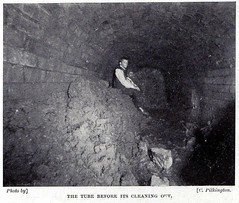

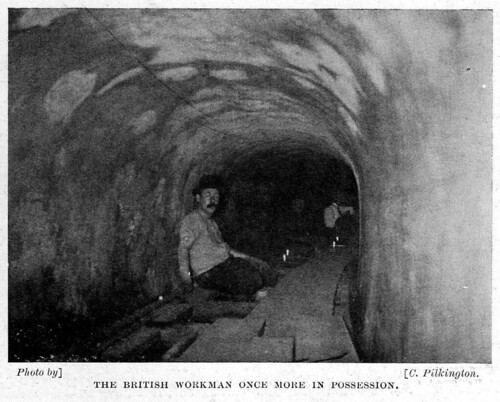

It was in 1895 that Mr. Thelfall first entered the disused tunnel after struggling and squirming through a heap of debris and lumber in a basement of Euston Station alongside Seymour Street. For many yards from the entrance of this terminal there was a trough to allow of the air propelling a car to escape and thus reduce the impacts on the receiving buffers. An incautious step upon the rotten wooden platform here precipitated the unwary explorer into three feet of stagnant water, but he nevertheless kept his ardour dry, and after several weeks practically completed his inspection of the whole tunnel (excluding the platform below Holborn Viaduct, which he found full of water), and decided that a fair expenditure would put it in working order for the propelling of cars by electricity.

It was in 1895 that Mr. Thelfall first entered the disused tunnel after struggling and squirming through a heap of debris and lumber in a basement of Euston Station alongside Seymour Street. For many yards from the entrance of this terminal there was a trough to allow of the air propelling a car to escape and thus reduce the impacts on the receiving buffers. An incautious step upon the rotten wooden platform here precipitated the unwary explorer into three feet of stagnant water, but he nevertheless kept his ardour dry, and after several weeks practically completed his inspection of the whole tunnel (excluding the platform below Holborn Viaduct, which he found full of water), and decided that a fair expenditure would put it in working order for the propelling of cars by electricity.

Having discovered the tunnel and realized its effectiveness the still more difficult duty devolved on Mr. Thelfall of finding its owners, the original shareholders, or their heirs, together with the necessary plans and papers. It was indeed strange that the mouth-open tunnel, separated from a busy street by merely an iron railing and a few steps, should remain undiscovered even by these of our community whose misdeeds or intentions force them to hide from the inquisitive glare of X2671’s bull’s-eye lantern and the clink of his handcuffs. In the troublous times of 1883-4 when misguided wretches were attacking with dynamite bombs London’s main thoughfares and buildings, one shudders to think what the knowledge of the tunnel’s existence might have led to on the part of these miscreants. Some dynamite, a line of wire, and a battery spark, and the Nihilist, Anarchist, or Fenian might have sat in safety and ripped a tract of death and desolation throughout the Metropolis. But there are no apparent signs that the tube was ever the hiding-place of any human being. Merely a few, skeletons of rats and, presumably, cats judging by the size – what a Homeric combat of “fighting against odds” do these crumbling bones suggest ! – and here and there umbrella-shaped fungi where the water condensation is greatest.

Having discovered the tunnel and realized its effectiveness the still more difficult duty devolved on Mr. Thelfall of finding its owners, the original shareholders, or their heirs, together with the necessary plans and papers. It was indeed strange that the mouth-open tunnel, separated from a busy street by merely an iron railing and a few steps, should remain undiscovered even by these of our community whose misdeeds or intentions force them to hide from the inquisitive glare of X2671’s bull’s-eye lantern and the clink of his handcuffs. In the troublous times of 1883-4 when misguided wretches were attacking with dynamite bombs London’s main thoughfares and buildings, one shudders to think what the knowledge of the tunnel’s existence might have led to on the part of these miscreants. Some dynamite, a line of wire, and a battery spark, and the Nihilist, Anarchist, or Fenian might have sat in safety and ripped a tract of death and desolation throughout the Metropolis. But there are no apparent signs that the tube was ever the hiding-place of any human being. Merely a few, skeletons of rats and, presumably, cats judging by the size – what a Homeric combat of “fighting against odds” do these crumbling bones suggest ! – and here and there umbrella-shaped fungi where the water condensation is greatest.

Stranger almost than the loss of the tunnel was the disappearance of its owners and the papers that would tell who they were. After eighteen months hard search in Government offices and the five parishes through which the tube runs, Mr. Threlfall realised that neither they nor the original contractors had a single plan of the route. It was not until after a wearying system of inquiries half over England and on the Continent that Mrs. Frances Rammell, the widow of the late T. W. Rammell, a famous engineer, was discovered and, through her remarkable energy, the original plans were eventually brought to light.

Stranger almost than the loss of the tunnel was the disappearance of its owners and the papers that would tell who they were. After eighteen months hard search in Government offices and the five parishes through which the tube runs, Mr. Threlfall realised that neither they nor the original contractors had a single plan of the route. It was not until after a wearying system of inquiries half over England and on the Continent that Mrs. Frances Rammell, the widow of the late T. W. Rammell, a famous engineer, was discovered and, through her remarkable energy, the original plans were eventually brought to light.

To realise the commercial value of the tunnel’s discovery and rehabilitation it is necessary to have some slight idea of the extent of mails and parcels passing not only between Euston and the G.P.O., but also between Eversholt P.O., the other local offices en route, and the two main termini. Practically all the heavy post to the north of Great Britain passes through Euston Station, and the heaviest hour of the day sees a total of eleven tons of postal matter leave the G.P.O. for the North-Western Central Station. At present vans carrying from one and a half to two tons each, and taking twenty-four minutes under the most favourable circumstances, make the connecting journey. Heavy traffic, fog, greasy pavements, or other drawbacks to vehicular motion, may double the time occupied. The contract time for the delivery of the mails to the various stations is eight miles an hour, and the enforcement of this rate of speed is one of the G.P.O.’s chief difficulties. For a time motor-cars were tried, but without success. The road to Euston is perhaps the most difficult of all to make progress along, and there is no doubt the tunnel, when fitted will be an enormous convenience to the postal authorities.

When the tunnel is ready, a copper strip will be laid in a trough between the rails, from which an electric-motor drawing a maximum load of seven cars, will pick up the electric current by a roller contact. The current will be supplied by the electric lighting companies and there will be therefore no initial expense for setting up a generating plant. About forty miles an hour, or under two minutes for the journey, will be the highest speed to be attained; and as each car will carry a ton of mails or parcels, seven tones will fly from post-office to station in a twelfth of the time taken by so many horses and vans. There is nothing chimerical or ‘extravagant in Mr. Threlfall’s scheme. The highest experts have endorsed it, and a firm of railway contractors, and also of electrical engineers, now have the preliminary work in hand, on their own stipulations that not a penny is to he paid them should the line-prove a failure, and in consideration of shares and debentures in the new company – the London Dispatch Company – being allotted to them.

When the tunnel is ready, a copper strip will be laid in a trough between the rails, from which an electric-motor drawing a maximum load of seven cars, will pick up the electric current by a roller contact. The current will be supplied by the electric lighting companies and there will be therefore no initial expense for setting up a generating plant. About forty miles an hour, or under two minutes for the journey, will be the highest speed to be attained; and as each car will carry a ton of mails or parcels, seven tones will fly from post-office to station in a twelfth of the time taken by so many horses and vans. There is nothing chimerical or ‘extravagant in Mr. Threlfall’s scheme. The highest experts have endorsed it, and a firm of railway contractors, and also of electrical engineers, now have the preliminary work in hand, on their own stipulations that not a penny is to he paid them should the line-prove a failure, and in consideration of shares and debentures in the new company – the London Dispatch Company – being allotted to them.

Given the success of this electric postman with all restraint of enthusiasm it may be hinted that Paddington, Waterloo, London Bridge, Charring Cross and Victoria are likely to have similar connections to the G.P.O.

Given the success of this electric postman with all restraint of enthusiasm it may be hinted that Paddington, Waterloo, London Bridge, Charring Cross and Victoria are likely to have similar connections to the G.P.O.

Realising the possibility of this and remembering the many journeys made by passengers on the pneumatic railway, it does not seem audacious to imagine high officials or other prominent personages availing themselves daily of this rapid route between the City and the stations, until finally the mails and parcels are relegated once more to the vans and the tunnel devoted wholly to passenger traffic at saloon charges.

Absolutely fascinating! I knew of the existence of unused tunnels under London, some that go under the Thames, and used by BT as conduits for telephone cables, but I’d never heard of a pneumatic rail line under London.

What an amazing story, straight out of HG wells or Julius Verne. One wonders how many more lost and forgotten inventions of the Victorian era await rediscovey.

I was particularly struck by the line “In a Times leader of February 10th, 1863, I have found …” – it made me smile at the thought that Harry Thompson was the IanVisits of his day!

the British Postal Museum & Archive have two of the original vehicles from the pneumatic railway at their store in Debden – you can see them here.

A visit to Crystal Palace museum which mentions some of the above railway systems in their displays is worth a look