A developer ripping out the heart of a much loved part of London is a common enough story, but with the music hub of Denmark Street, were the critics right, or is something more interesting going on?

Certainly, if you wander around the area next to Tottenham Court Road, it seems to have been filled with modern glass buildings and a huge video wall of adverts that sprung up from the clearance needed to upgrade the tube station, and a far cry from the ramshackle cluster of decoratively decaying buildings that were here before.

Some of the changes were essential — such as creating more pedestrian space as the pavements were dangerously narrow around the tube station and Centrepoint was an island in a busy road roundabout.

But did the rebuilding works also rip out the heart of Denmark Street, long a hub for music shops selling instruments and a home to many early pop stars? While it’s obvious what’s been built here with the huge advertising screens and new glassy buildings, what’s more interesting is why.

The property developer, Laurence Kirschel started buying up the area in the mid 1990s, having already realised that music was going to struggle in this new internet age, but also that the alternative, live venues, were themselves also struggling.

His idea has been to create a music hub, with a mix of venues for live music, shops and offices for the people working in the music industry’s commercial side.

Part of the thinking behind the idea is that while Denmark Street was famous for music shops, it was a fading glory with a risk of music shops being priced out of the area. There were already non-music shops in the street, and the largest occupants were the local job centre and a TK Max. There’s even a memorial plaque to Tin Pan Alley on the side of the building to the 1911-1992 era. Retail stores in central London can command high rents, and it’s likely that untouched, the street would be now dominated by coffee and sandwich bars.

The commercial difficulty is how to prevent the loss of the music shops, while still being a viable landlord who doesn’t hike rents to sandwich bar rates. And that’s why there’s now a huge glowing advertising display on the corner facing the tube station.

By clearing the north side, and building a new large venue underground, there’s space for office and commercial spaces above ground, and the money making machine that is the huge advertising screen. While it’s wrong to say that one subsidises the other, it’s correct to say that having the whole site under one developer means there can be cross-support between the different outlets.

So on one side is the bright lights of the nightlife economy and behind, a potentially reinvigorated Denmark Street lined with music stores.

To get to where we are though, the northern half of the site was being cleared anyway by Crossrail, and people with a good memory may recall that it was a pretty shabby spot covered in big adverts (plus ça change) and not really that interesting. As that was flattened for Crossrail, they preserved the facade of the buildings facing east, and then the cleared space was rebuilt to a design by ORMS with two main buildings — the very obvious Outernet on the corner, and behind the retained Victorian facade, a mix of offices and accommodation.

Undeniably, the most visual change is the arrival of Outernet – the huge block of a building that’s now a large advertising banner, not unlike Piccadilly Circus. This sits above a music venue with a 2,000-person capacity, which is entirely coincidentally the same as the Astoria used to have.

It’s a music venue as shorthand, but one of the problems with converted venues is that they lack flexibility, and this has been purpose-built to be used for, pretty much anything that needs a large empty space in central London for a few hours. Nighttime entertainment venues are often closed more than they’re open, which limits their cash-generating ability, so Outernet has been designed from the outset to be an all-day venue that can be used for a range of events. That means more revenue from the box and less reliance on revenue from other parts of the estate.

Candidly, a large empty box isn’t that interesting to look at, but from an engineering perspective, it’s fascinating. There’s a large concrete and steel structure, but the venue box sits inside that on an independent set of shock absorbers. You can see the gap between the inner venue box and the main structure if you’re in the building when the goods delivery lift doors are open.

For once that’s not to avoid the music disturbing the neighbours, but because the neighbours might disturb the music. It’s right above the Northern and Elizabeth lines.

When people dance or have conferences in Here London, they are just a few metres above the Elizabeth line. In fact, the Elizabeth line passes through the middle of what was to be their basement, so there are two basements on either side of the railway tunnels. During construction, they had to dig large deep piles along the outer edges of the railway tunnels, and then build a heavy concrete slab on top — in effect a series of giant staples to hold the railway in place and stop it moving.

The main structure also had to take into account the new Northern line escalators, as they pass right through the foundations, and in places, if you get to go behind the scenes, you can see odd looking truncations in the service stairs where they are coming close to the escalator shaft.

What had been a fairly monolithic block of buildings with an alley at the backs has been broken up with a new north-south corridor running through, and a new route created into Denmark Street by the simple method of demolishing a shop to create a new covered alley — lined, of course, with video walls.

Denmark Street itself is one of the few streets left in London with Georgian era housing facing each other on both sides of the street. Away from the music heritage, the Georgian buildings are what give the street some of its unique character if you look above the ground floor.

Sitting behind one of the shops was something else though – something that many people might not have realised the historic importance of — a 17th-century forge. Its interior had long since been cleared of the forge and was often used for small recordings and music performances, but as a building, it was a rare survivor. However, it was in the wrong place, as the plans were to build a 280-person music venue in the basement, so a team of heritage building experts were able to slide a new floor underneath the forge, wrap it in cladding and lift the entire building out in one piece. In fact, it was the same company that moved the St Pancras Water Tower in 2000.

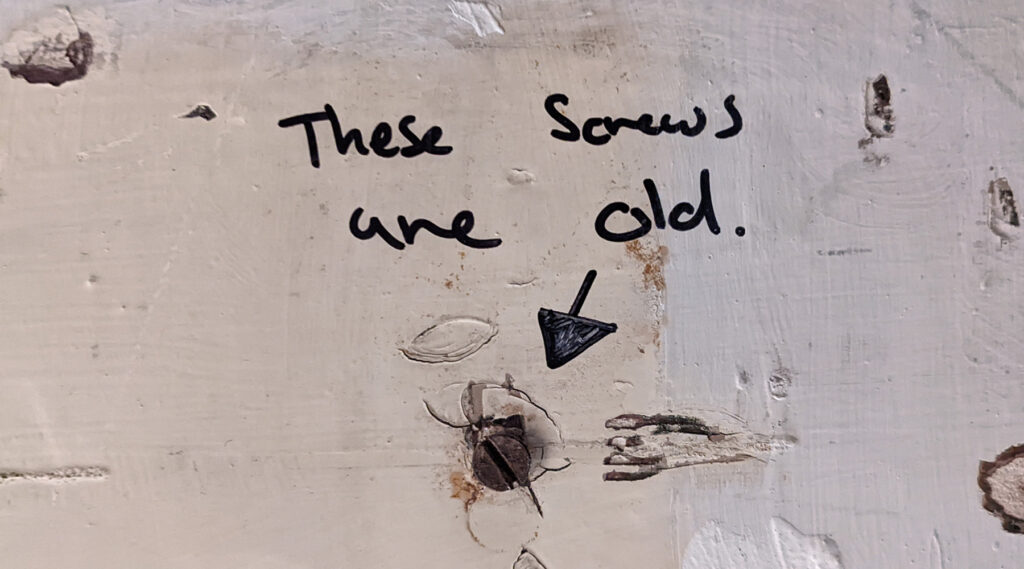

They later put the forge back where it came from, and is now the backspace in the bar and can be separated into a private music venue as well. If you ever went there when it used to have a small balcony at the back, you might skip a heartbeat or two to learn that when they were preparing the building to move, it turned out the balcony was barely hanging onto the wall.

That new basement music venue is also wired directly to a pro-bono recording studio that’s opening soon, so gigs performed there can be recorded in a professional setting at the same time. The recording studio will also be opened up to performers not using the basement.

All this faces Denmark Street, the area of change that caused so many protests that it was about to be gutted of its musical heart. Certainly, over the past few years, the backs of the buildings were rebuilt and shops had to either move out, or jump around addresses a couple of times to keep trading around the building works.

However, the works are pretty much finished now, and shops are moving back in.

To keep the music heart intact, Camden Council created a new planning designation for the street so that it has a presumption to music related occupants – the appropriately named Tin Pan Alley clause. The petition that was set up to save Tin Pan Alley turns out to have been opposing a development that was going to deliver exactly what the campaigners wanted in the first place.

Of course, there’s always the risk that in a decade or so, things will change, but at the moment, the intention to preserve Denmark Street as the home for music shops is secure. Yes, some of the ramshackleness has been lost in cleaning up the old buildings, but that goes for the wider music industry as well, which is far more commercially minded than it was in the early days of pop music when future megastars would hunker down in shabby rooms around the area to live and work.

Today though, the rooms are posher, and if you wander around look for the seemingly ordinary doors with rather grand looking snakes door knockers on the front – these are the entrances to the serviced apartments dotted around the site. Not quite residential and not quite a hotel, they are a hybrid between the two for short-term stays. The initial plans had St Giles High Street remaining a road, but it was later decided to pedestrianise that as well, and it’s now St Giles Square.

This is one of those developments that will always polarise opinion.

Those who only see the big advertising screens will decry the gutting of Denmark Street because they won’t wander around the back to have a look and see that it’s still there and still full of shops selling guitars and keyboards.

Denmark Street seems to have been saved, despite the naysayers.

Then there’s the glossy half of the development that replaced the shabby backs of buildings covered up in adverts and a busy road. Now, it’s a pedestrian space and yes, a very garish one, but that’s part of its appeal. People coming up the escalators out of the tube station for a night in town will arrive in a large open space dominated by glowing adverts, bright lights and all the panoply of the west end nightlife. It’s the bright lights of the city nightlife that appealed to most of us when we were young and fun.

I look at buildings in two ways — either they are memorable, or they create memories.

For example, the Gherkin is a memorable building, and much loved. However, no one is going to ever say that the average nightclub venue is a memorable building of architectural merit. The Astoria for all the angst that was caused when it was demolished was a disgusting fleapit of a building, a former theatre converted into a club space that was barely being held up by the sweat (and gods knows what else) that had soaked into the walls.

Yet it was loved, not because it was a memorable building, but because of the memories it created.

Likewise, the Outernet will be the Astoria of the future.

While the engineering geek in me bounces around in joy at the complicated difficulties of building it, what has been built is a very functional box of fairly minimal aesthetic appeal when all the lights inside are turned on. But for the generations to come, there will be the exciting anticipation of the long queue outside to get in, to dance and see favourite musicians as clever lighting and sound systems turn the empty box into something magical.

It will create happy memories.

And ultimately, that’s a good thing.

Do you know which venue was using the forge as a space before it was moved? was it the 12-bar? that had a tiny back room with a sort of upstairs where you could only see the heads of the band.

I’ve answered my own question with some minor googling.. yes it was the 12 bar http://www.urban75.org/music/12-bar-club-london.html

It’s hideous. Standing by the tube and looking toward Soho Place literally every building has gone and been replaced in the last decade.

This was a good read.

This article studiously avoids mentioning that the old Forge was the famous 12 Bar Club, where Adele and many others started out. There was a 30,000 petition for it’s return post development – which was written into the Section 106 planning consent. But it has not been offered that legal right of return. Why?

The venue has reopened, as the Lower Third – the very venue I write about in the article.

They’ve destroyed the character and energy of the place and made multi millions. The Developers destroyed 5 iconic music venues in the process. Anyone who worked and lived in Denmark Street will see this dreadful article as a PR piece ignoring the utter destruction of UK history and music heritage.