A large new tunnel is being dug underneath Euston station, by HS2, but not for HS2 – it’s for London Underground.

This is part of what’s known in the trade as “enabling works”, the sort of work that’s needed to prepare a brownfield site for what it is intended to become. That can be as simple as clearing rubble from a site, to major interventions such as moving sewers and utilities or decontaminating land.

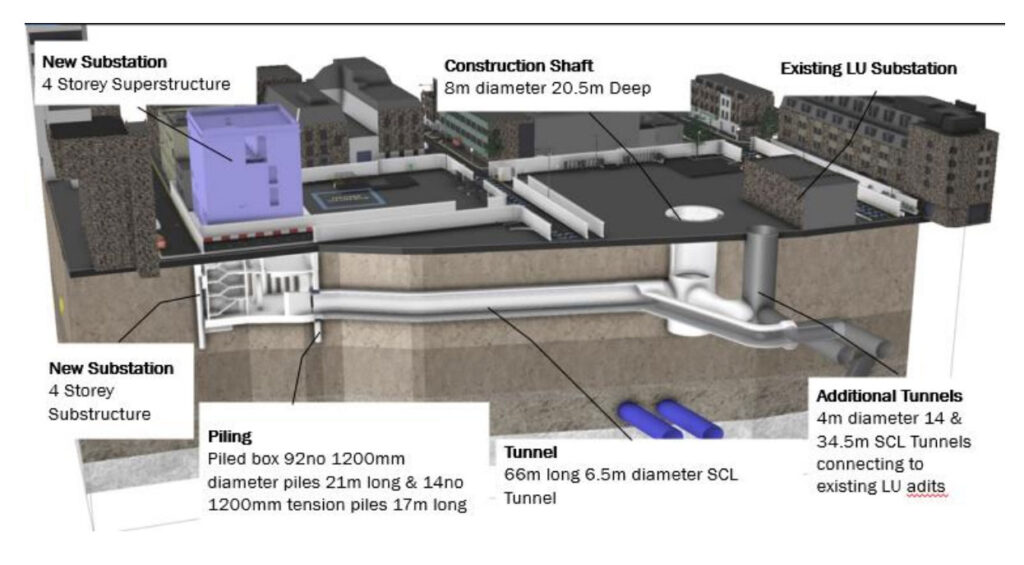

And at Euston, it requires the construction of a very large cube box above and below ground and a 90-meter long tunnel for the London Underground.

To understand why, leap back to the 1900s, when the Northern line on the London Underground was still two separate competing railways, and in the 1900s, the two tube companies opened separate tube stations at Euston, on either side of the mainline station. A deep-level tunnel linked the two tube lines, with a ticket office in the middle of the tunnel.

They didn’t last long though, and with an entrance inside Euston station serving both lines, the two separate station entrances outside closed in 1913. The Bank branch building was demolished in 1934, but the Charing Cross branch building survived. That building was gutted internally in the 1960s to provide space for a ventilation fan and an electricity substation.

The ventilation fan inside the station ticket hall – June 2016 on a Hidden London tour (c) ianVisits

However, although it’s still in use pulling hot air out of the tunnels, it is also sitting right in the middle of the planned HS2 station at Euston. In fact, it’s where the platforms will be, so it had to be moved.

And that is why HS2 is building a replacement building, known as a Traction SubStation (TSS) on a side street to the south of the station. As explained by Rob Williams, senior project manager at the Mace Dragados JV that is carrying out the construction work, the new building will provide ventilation and electricity for the Northern line, but to get those from the new building to the Northern line, they had to dig a 90-metre long tunnel.

A very big tunnel.

Digging the tunnel and the new box proved to be a challenge, not least because it’s right in the middle of central London and surrounded by lots of other occupants, so noise, dirt and deliveries all needed to be managed to reduce their impact on the residents, but also because the tunnel had to avoid affecting the Northern line just beneath it, a high power electricty tunnel just to one side and major water mains to the other. The work was described as threading a needle to squeeze the tunnel in the narrow gap between all the other tunnels down here.

There are two building sites, one for the new box and one for a shaft down to the new tunnel.

The shaft is a mixed design, being a series of concrete rings pushed into the ground for about 10 metres through the softer surface soils until they reached London clay in June 2021, and could then dig down and spray the concrete onto the clay walls to stabilise it. During construction, a large grey shed was placed over the top to dampen down the noise for the people living and working around the site.

Normally, the sprayed concrete is reinforced with steel fibres mixed in with it, but an unexpected problem some 3,000 miles away caused a change of plans. That was when a cargo ship got stuck in the Suez Canal, and one of the many side effects was a shortage in the UK of fibres for use in sprayed concrete. So plans at Euston changed to using steel rebar, which is usually reserved for areas where stronger walls are needed. All because of a stuck boat.

The shaft was completed in August 2021.

Just to the south, a big square hole was being dug into the ground.

To build the box, over a hundred thick interlocking piles were driven down into the ground, about half of them are 20 metres deep, the same as the box, and half are longer to help anchor the box into the ground. Once the site was surrounded by a concrete wall, they dug down, adding reinforcing beams in the corners to stop the box from collapsing, until they reached the bottom.

You may have heard on occasions stories about tall buildings sinking slightly into the ground after construction. Here in London, we have the opposite problem. London clay is very heavy, and the weight compresses the ground beneath it. However, if you dig a deep cube in the ground and remove tons of clay, the ground that was being crushed by the weight above starts to expand. It heaves upwards. To prevent that from happening, a few weeks ago, a convoy of lorries delivered enough concrete to fill the bottom of the box with a very heavy 1.5 metre slab at the base to hold the box in place.

It’s the largest continuous pour of concrete on the HS2 Euston project to date.

Meanwhile, as the box was being dug down, over at the shaft, two tunnels were being dug, one towards the box, and the other towards the Northern line.

The tunnel was dug manually, using diggers and sprayed concrete, and then waterproof lined and given a final internal seal of concrete was added earlier this year. Just as at the box, the tunnel needs a heavy concrete base to stabilise it in the clay so that it won’t affect the HS2 station above.

A major event that took place recently was when the new HS2 tunnel broke through into the 117 year old Northern line tunnels. These are the customer tunnels that used to lead from the platforms to the old ticket hall, and today are used for ventilation.

The breakthrough point between the new tunnel and old Northern line passenger tunnels – Photographer Monica Wells (c) HS2

Now that the modern tunnels have been completed, work is underway to fit them out, and build a wall right down the middle. One side will be for electrical cable and the other side for ventilation.

It would have been easier to avoid the wall, but it would mean that ventilation maintenance could only be carried out by staff trained to work in proximity to high voltage power cables, so separating them will make long-term maintenance easier. That separation applies to the box as well — which will be split down the middle with a solid wall. One half will have a replacement ventilation fan installed to pump cool air into the Northern line, and the other side will be for the electrical substation.

The new 3-storey high fan being installed here will be more efficient and reliable than the old and modern controls will allow TfL to remotely monitor if the fan stops running and quickly dispatch a maintainer to fix the issue. These features should keep the asset available for a greater percentage of the time which would in turn have a positive effect on the temperatures on the Northern line.

When completed, in 2025, there will be a large “sugar cube” on a side street clad in the same sorts of tiles use on older tube stations, but built by HS2, and what people won’t see is the deep basement underneath it, meaning that the sugar cube is actually 7-storeys in height, and people will never see the long tunnels that link the box to the Northern line tunnels.

All this is being built by HS2 but will be used by London Underground to keep the Northern line running.

Fascinating, and a great explanation.

Any chance of a tunnel & escalators to link Euston tube platforms to Euston Square on the Circle/Met/H&C?

With all the destruction of the 1960’s rebuild, it’s amazing that no connection was built.

That is part of the plan.

https://www.ianvisits.co.uk/articles/a-new-london-underground-entrance-for-euston-station-36378/

What will happen to the Leslie Green designed station on the corner of Melton Street and Drummond Street? Will the visible bit remain? What will it be used for?

That will get dismantled eventually as it in the way of the new platforms

Looking at the old station entrance on the corner of Drummond Street and Melton Street, my question is why there are two buildings – one clad in purple tiles and the other in stone. Any idea?

The brick building was added later.

The brick building was the original substation, and was built at the same time as the tiled station building. All of the original substations on the three lines financed by Charles Yerkes (Bakerloo, Piccadilly, and the Charing Cross branch of the Northern) were built from brick, with slightly different designs. This building has remained the substation, with the station being re-equipped with a ventilation fan after closure (date uncertain, but by 1929).

Looks decent where abouts in the old tunnels will the new tunnel link up? South wall by the old lift shafts