It’s 1942, and the air raid warnings are screaming. People in select parts of London hurry to their nearest tube station to take shelter. But unlike many thousands of others around the city, these few fortunate people were to sleep in a network of dedicated tunnels dug next to the stations.

These were the deep level shelters, which could house up to 8,000 people each, and have rarely been seen by modern London, until now.

This weekend, one of them is open to the public.

However, for all their mysterious allure, there are almost as many myths about these tunnels as there are Hollywood movies about the war.

During the early months of the blitz, people were using railway arches, church crypts and tube stations as shelters, and it was mounting public pressure, as well as the generally unsanitary conditions of basement shelters that forced the government to build a series of deep shelters.

Even then, there was some doubt about their use — with Mr Herbert Morrison noting when announcing the new shelters, that even if they doubled the size of the tube network, that would only protect 1-in-6 of the population.

But in November 1940, the plans were made public, and construction started, largely by hand, although a tunneling shield was later acquired to speed up the works.

As befits wartime economies, some of the tunnel linings were left-overs from other London Underground tunnels — and the markings of the London Electric Railway, and the LTPB can be seen on them.

However, metal ran out, and concrete replaced the iron.

One of the most common claims about the tunnels is that they were to be used after the war as a high-speed railway line. The tunnels sat next to tube stations that they would later bypass if they were all linked up, letting commuters from South London skip “the claphams” to get to the city faster.

It’s a bureaucratic fiction, born of the need, even in war time to justify the massive cost of building the tunnels. London Transport had no interest in a doubling up the Northern Line, and even then were far more interested in what would become the Victoria Line, and maybe eventually, Crossrail 2.

However, to get funding for the tunnels, the polite fiction was created that they would have a post-war use. In fact, they did, but not for what the planners expected.

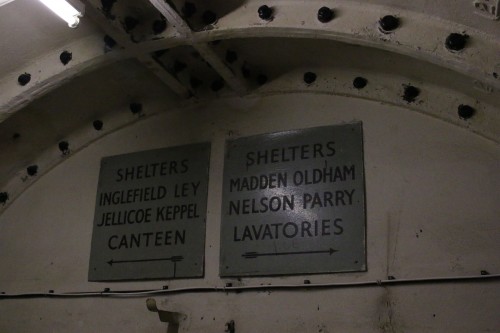

Once completed, the tunnels opened to the public, who had to pay to use them. Just as restaurants above ground were exempt from food rationing, so the same applied to the modest canteens installed below ground.

Although people rather resented having to pay 2p for a cup of tea, which was double the rate above ground.

Much has been said over the years about the atmosphere below ground, of stiff upper lips and parties, but the reality was sleeping next to rumbling tube trains on the Northern line and being evicted at 7am the next morning.

The beds were simple, in long dormitories, and it’s unlikely that many people would have been able to stretch out on the bed. People had to bring down their own bedding each evening, and remove it the next morning, using the same spiral staircases used by visitors today.

Toilets were provided, of the chemical sort, and the effluent removed every few days by means of a high pressure hose pumping the contents of a tank to the surface.

Unlike today, smoking was permitted underground, so along with the smells and sounds, the tobacco smoke, the chemical latrines, the rumbling trains, it wasn’t the most salubrious place to spend the night.

Clapham South was built for 8,000 people, but it never reached half its full capacity, even on the busiest nights. For all the public pressure to build them, they were not that heavily used.

After the war ended they found a new use though — not for high-speed tube trains, but as cheap hotels.

Some of the beds were made a bit more comfortable, and the bottom smaller of the three in each row removed from use.

Famously, Caribbean arrivals on the Empire Windrush were housed here, although few stayed for long, and all were gone within the month to more conventional accommodation.

The army used them as accommodation while demobbing soldiers.

But the most people who used the tunnels as hotels were visitors to London for the Festival of Britain. The tunnels were ideal cheap accommodation in a city where many people were still living in temporary housing and hotels were scarce.

Unfortunately, a fire at the Goodge Street shelter in 1956 and the difficulty of evacuating the tunnels put paid to the idea of letting the public down there on a regular basis.

And they have been generally either empty, or used for storage ever since. An unseen legacy of the war. Until now.

Sadly, tickets to go on this weekend’s tours sold out ages ago, but more tours, possibly as a regular event are planned.

I believe the signage with the Naval Officers only dates from 1951 and is not original to the 1940’s shelter.

I was intrigued by your statement that the Northern Line express line was a bureaucratic tale of fiction. I can only find articles indicating that LT of the day did want an express, or built them with the option to transform them into running tunnels. It’d be really fascinating if you could share the source of that information please.

Unfortunately, the source is buried in my boxes, but it I recall it being well cited and from a reputable writer of tube history.

I’ve also come across snippets myself in research suggesting that doubling the tunnels was never much more than a wishful desire.

Amazing! I never knew. Thanks very much for the reply!

I cannot understand why they have not been made into small business offices. They can be subdivided into cubicles with phone and computer lines from a common modem. Starting new small businesses who can work and mesh with each other at such close quarters would be great. They need low cost rentals to start small businesses and this woukd be fantastic. A business mentor could be in residence and very few businesses would fail.banks would assist with business loans to companies who start efficiently. This is a great asset for london.

As mentioned in the article above, they no longer comply with fire safety regulations for evacuating people safely.

…also, would you really want to work in a “basement” all day every day?

Goodge Street deep level shelter was used by Eisenhower and latterly was repurposed as a radar coordination centre, then as the international phone exchange and a backup phone exchange.

A fascinating glimpse of the past. Some tunnels have already been repurposed by friends of mine growing vegetables underground http://growing-underground.com/

Oh lucky you.What a wasted space.Either it will scooped up for “Secure,data,storage” or government has ideas / plans.Without air filtration ,fairly useless.Who is the current owner ?

When are the next tours open to the public as I would like to book tickets to see the tunnels thank you

Hi there,

Is there a website for this to book tickets? Or do you turn up on the day?

Thanks

The link to the event booking details are in the article above, although they sold out a very long time ago.

How much per ticket! I nearly fell over, at those prices they could afford to extend the tunnels to modern.

Far too expensive!