Almost everything you think you know about Nero is probably wrong. He didn’t fiddle while Rome burned, probably didn’t kill his wife, might not have killed his mother, and even his suicide is in doubt.

Possibly the most maligned man in history wasn’t the monster that myth has made him out to be, and while hardly a saint either, Nero is starting to look like a much more interesting person as a result.

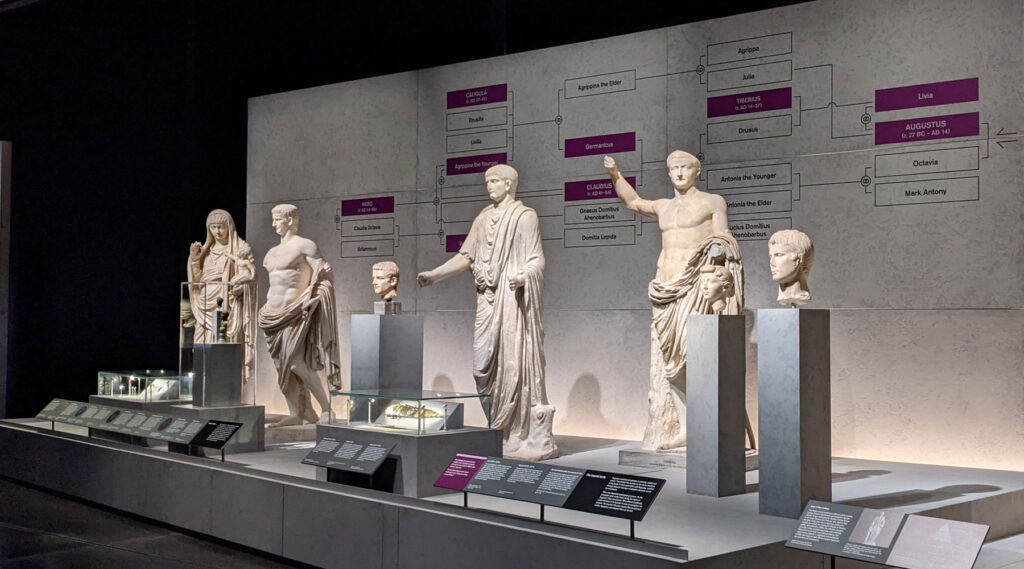

This is the man who is the topic of the British Museum’s summer blockbuster exhibition: Nero: the man behind the myth.

A lot of what we think we know stems from later histories written by people seeking to reinforce a dodgy hold on power as Nero’s successors. Hollywood and the BBC took those stories and created the iconic image of a vain mediocre man who grew fat on cruelty.

Peter Ustinov’s Nero in Quo Vadis looks remarkably like a bust of Nero that opens the exhibition, except that it’s largely a bad 17th-century restoration from just a few original fragments. As close to looking like Nero as the famously bad bust of the footballer Cristiano Ronaldo.

More realistic is the youthful Nero who opens the exhibition proper, probably carved around the time he was adopted as heir presumptive by Claudius.

The exhibition is very much what you might expect from Rome – lots of big marble statues and lots of small artifacts. Our image of Rome being very much temples and statues, any exhibition about a Roman Emperor needs to include them – even if (whisper it quietly), Rome didn’t really look like the Hollywood version.

That’s not because Rome burnt down, it was often doing that anyway, the tight narrow badly built houses often several stories high were a fire trap waiting to happen. And contrary to the popular image, Nero wasn’t even in Rome when it burned down, being away in Antium, and when he returned, spent a lot of effort on rebuilding the city.

Much of the later tales about his lavish palace were true, but were also written by successors who conveniently overlooked their own lavish houses, and deeply resented Nero’s taxes on the rich to fund the rebuilding work for the rest of Rome’s residents.

That seems to be the lesson from this exhibition, that Nero was popular with the people who didn’t matter – the great mass of Rome’s population. The people who mattered, the rich and politicians hated him.

It was probably that populist attitude that was to doom him.

Away from Rome, one of Nero’s defining moments was here in Britain, and Boudica’s uprising. London fared badly, but Colchester was destroyed and the exhibition doesn’t shy away from some of the more brutal aspects of rebellion, with bones showing the effects of sword cuts, and the following restoration by Rome, the huge metal chains that convicted slaves had to wear.

Rome, and Nero was not kind to those who rebelled against its rule, as the exhibition shows with an example of what happened if a slave rebelled against his owner.

Eventually, though, Rome has enough of its Emperor and itself rebelled against him. He was sentenced to death in absentia, and may have committed suicide, although he might have asked a servant to kill him, it’s uncertain.

What happened next is certain though – the Year of Four Emperors, as different people vied for the top job, until eventually, Vespasian emerged triumphant.

The exhibition finishes with a bust of Nero’s eventually successful successor, Vespasian. Except, it’s a bust of Nero that’s been recarved to look like Vespasian. The ghost of Nero hovering over him to the end.

The exhibition doesn’t fully answer the questions about Nero’s reputation as the truth is just too deeply buried in the depths of history and later revisionism. Nero will never be reclaimed as a good man, as he probably wasn’t, and images of fiddling while Rome burned are too striking an image to ever die off — appearing forever in modern political cartoons as a metaphor for bad government.

What it does do is educate us a bit about the man behind the myth, and in this modern era of fake news and conspiracy theories, reminds us of the importance of always questioning the motive of the writer when reading a news article.

Packed full of rare survivors from Nero’s reign, this is the summer blockbuster exhibition that we’ve all missed this past year.

The exhibition, Nero – The man behind the myth is open at the British Museum until 24th October.

Tickets need to be booked in advance from here.

Exhibition Rating

British Museum

Great Russell Street, London

WC1B 3DG

I really want to go, but I’m not happy about BP being the sponsor. I feel this is an important time to support the BM and also an important time not to support BP.

What to do?

Stay home then.