Two years ago, the world celebrated as the first Covid vaccine was approved for use, and now, the Science Museum is taking a look at how we got to that momentous moment.

The new exhibition, Injecting Hope: The race for a COVID-19 vaccine, has a bit of a challenge, as the pandemic was not just a scientific challenge, but it seared much of society with lockdowns and deaths. It’s still a very raw emotion, and an exhibition has to tread carefully between the triumphant celebration of science while being aware that it’s still a painful memory for many of us.

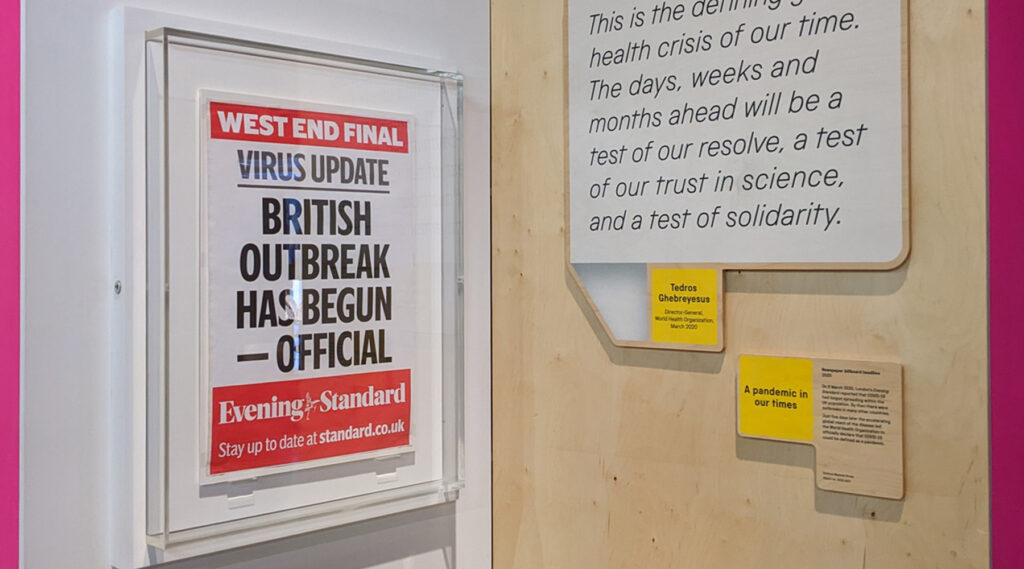

It opens with a bit of a hit to the guts though, with a corridor of news reports from the pandemic, from the early suspicions that something is happening somewhere else to the evening when nearly 27 million people watched the Prime Minister announce that the country would be going into lockdown, onto footage of empty streets, empty supermarket shelves, and battle-weary nurses.

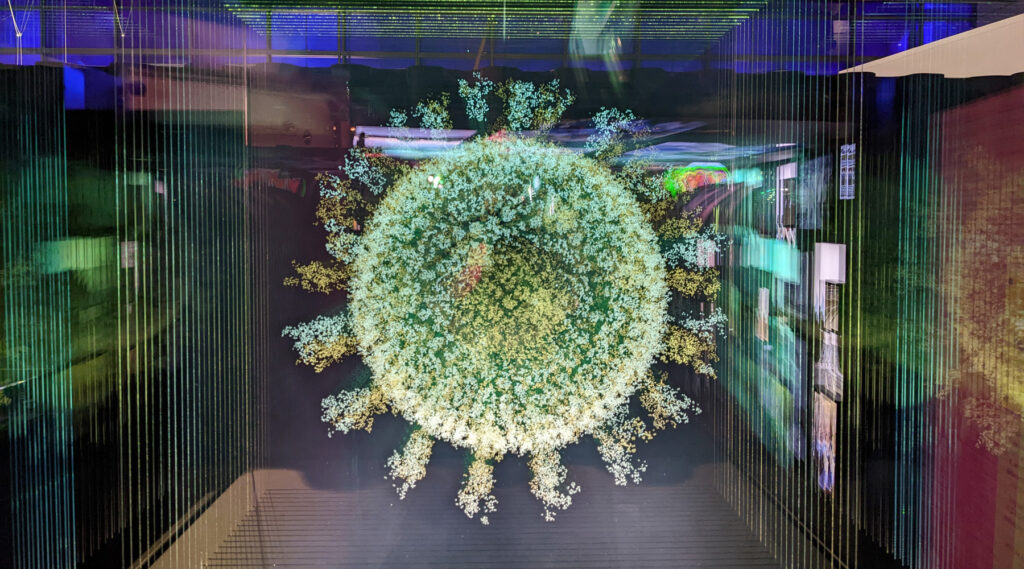

Then, there it is, the damned thing itself — blown up to a vast scale, the SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused all the problems. It looks almost beautiful here, an ethereal ghostly work of art cast out of sheets of glass almost hovering serenely in space.

The rest of the exhibition though looks at how scientists worked to defeat it.

Opening with explanations about how this family of viruses were originally discovered, to the concepts of vaccinations, with Edward Jenner’s smallpox needles, and explanatory videos – the bulk of the exhibition is about Covid-19 itself.

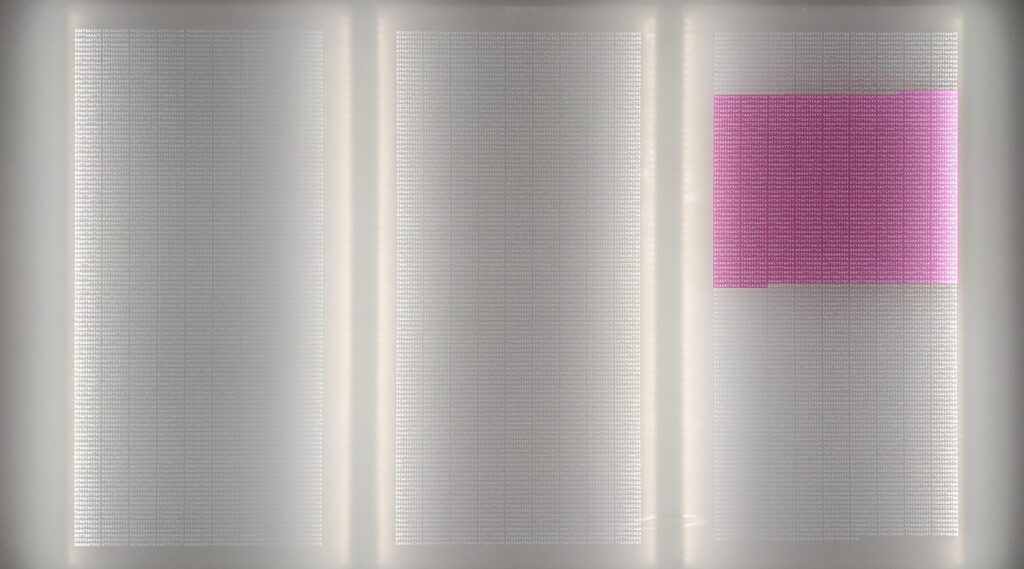

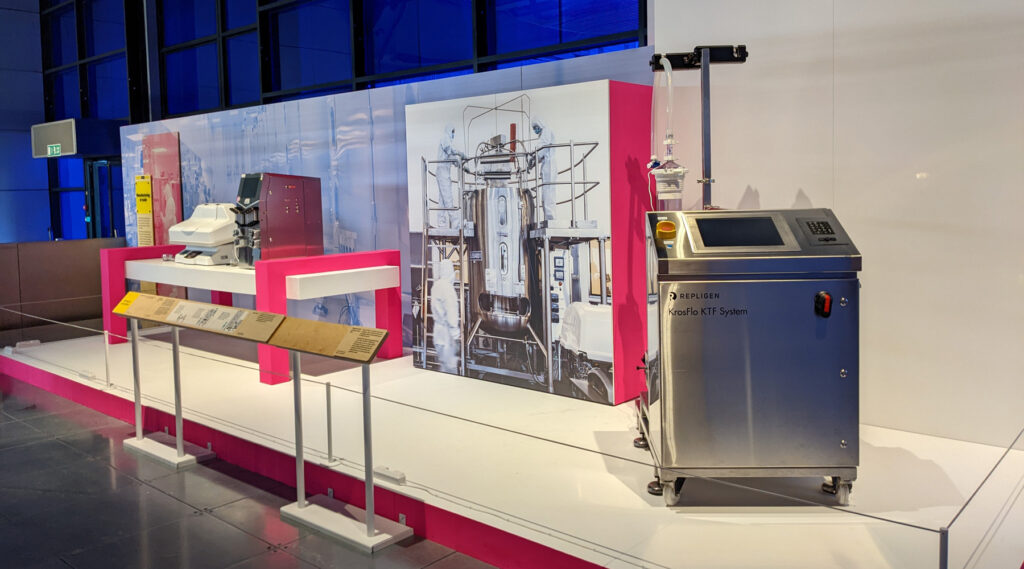

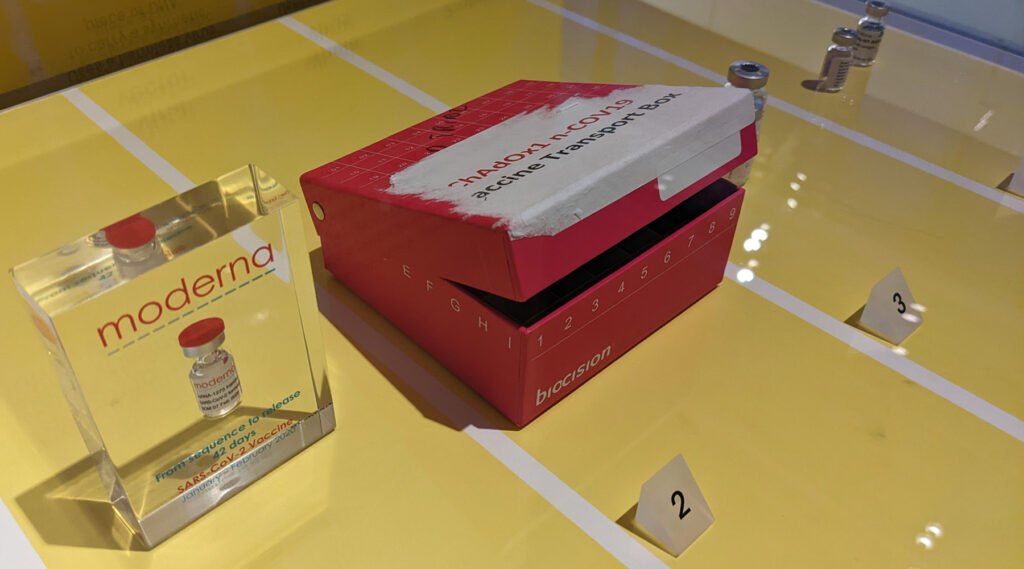

It’s a mix of an exhibition, and all the better for it, but mainly shows off the scientific equipment used to develop a vaccine — ranging from the small handheld test equipment to the vast machines that kept researchers safe and others that manufacture the vaccine itself. The virus’s DNA code is shown on a wall, and do read the explanatory notice next to it as to why some of the code is shown coloured in red.

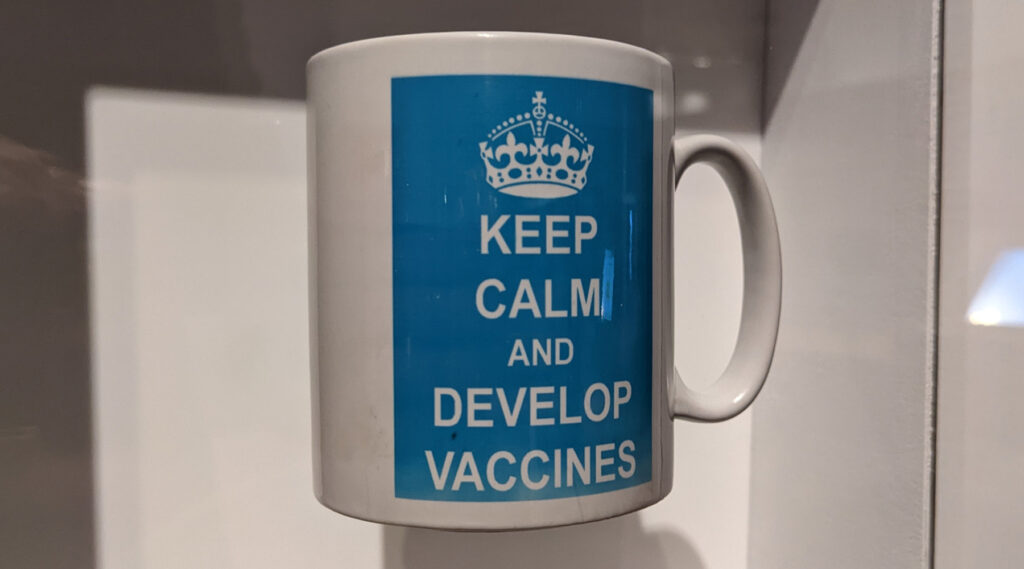

A lot of the exhibition though is about the people, from sometimes simple things such as Professor Tess Lambe’s laptop computer to Sarah Gilbert’s Keep Calm and Develop Vaccines mug – the only time I have seen the Keep Calm meme and smiled to see it — and even a pair of joky leggings worn by Elisa Granato, the first person to be given the Oxford trial vaccine.

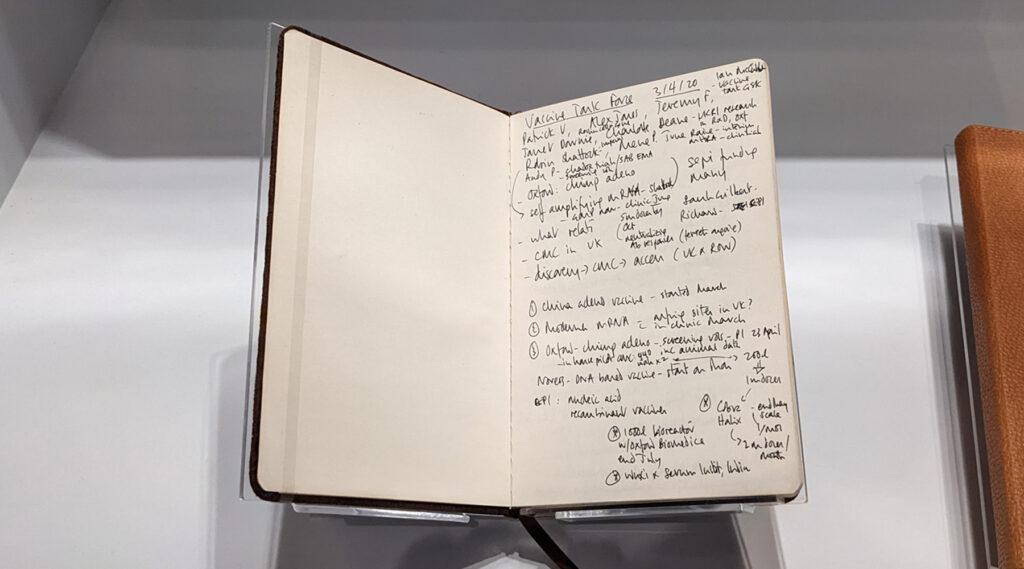

Kate Bingham’s notes from the first meeting of the vaccinee taskforce are here, opened to show the first handwritten thoughts that were to later transform into a huge logistical challenge that might be needed if a vaccine could be found. You may ponder what was written on the other pages in days to come when dealing with politicians and the news media were fraught.

As a video explains, developing a vaccine usually takes years to get from invention to use, mainly because of a shortage of money and a shortage of volunteers — which wasn’t a problem with Covid, and there’s a lovely video with interviews from some of the volunteers who took those early jabs.

A film of the production line at the Serum Institute may remind some of those Schools TV shows that show how food is mass-produced.

This coming Thursday marks the 2nd anniversary of Margaret Keenan getting the first official jab, but also next to her Xmas jumper that she donated to the exhibition is the medical top worn by the nurse who jabbed her, and with a sticker that the nurse had had the jab that people used to think mattered – for the flu.

During the pandemic, our efforts to fight it occasionally went wrong, of course they did, it would have almost been suspicious if they hadn’t. But I take away from the pandemic, for all the hell it put people through an uplifting message.

Lots of focus on scientific breakthroughs are obvious and are thanks to advances in science. However, I find something else to be impressed by and that’s the logistics involved in getting the science into people’s arms.

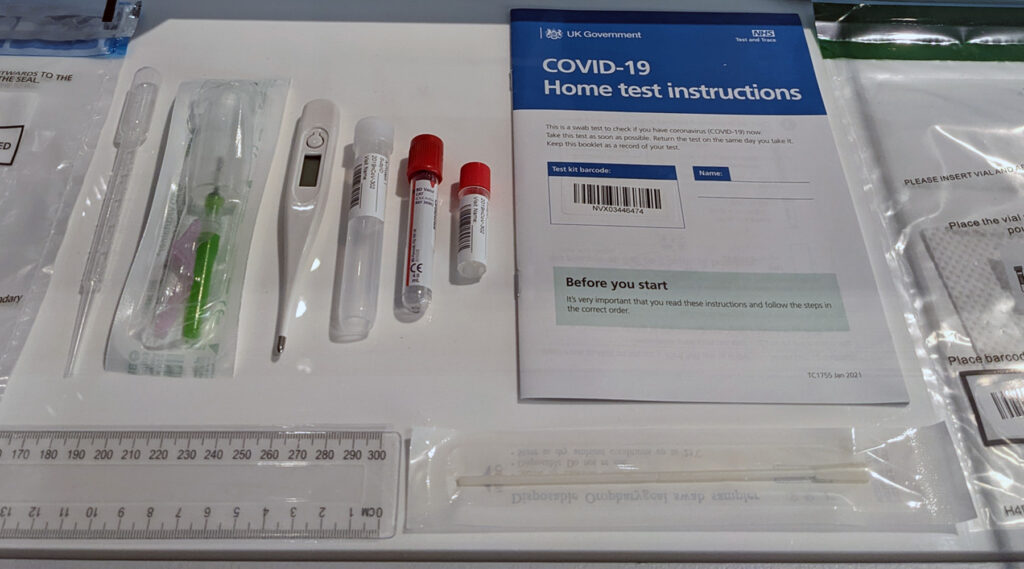

Experts in logistics were brought in early to plan the rollout and it’s clear when you look back that there were some exceptionally clever people working in those teams. The home delivery covid test packs impressed the heck out of me when I got my first one – from how they packed it so it would fit through a letterbox, down to the small hole cut into the package to hold the test vial so people didn’t need to find something to hold it upright.

The exhibition rightly shows the planning that went into where to place vaccination centres, and there are maps on display that highlight the many variables they considered, from the population density of people high up the list to the availability of transport. Looking for buildings with large spaces, even the Science Museum became a vaccination centre.

A large high level map of the UK may leave you with thoughts of the maps used in WWII’s Battle of Britain.

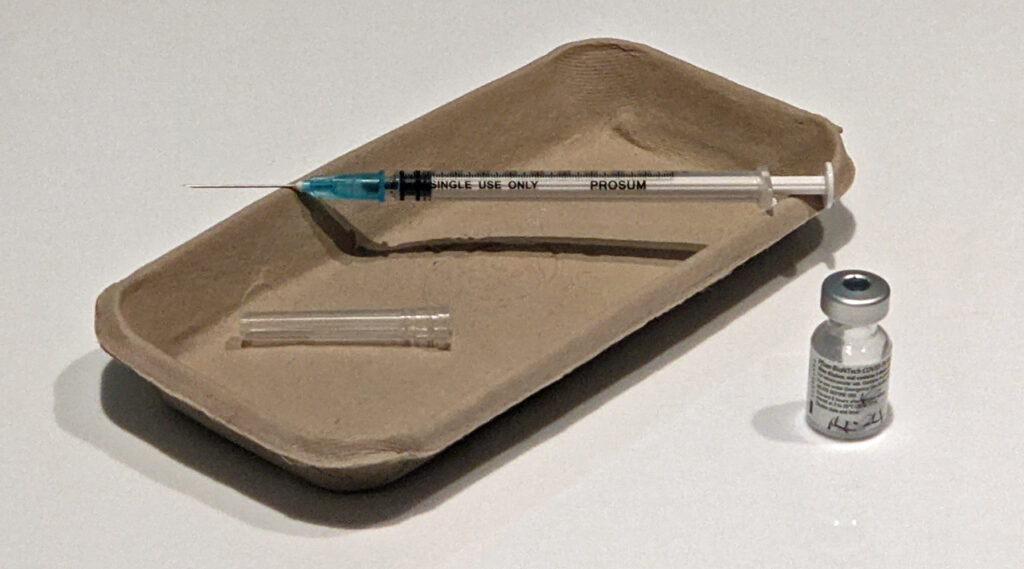

The exhibition ends with a glass case of the side of the vaccine many of us saw, from the little stickers that so many wore proudly until it fell off to the little cards we put in our wallets.

Just think, someone somewhere designed those cards and labels, and I wonder how many people have had the opportunity to design something that pretty much the entire population of the country would be so keen to get.

A symbol that freedom was on the way.

The exhibition, Injecting Hope: The race for a COVID-19 vaccine is at the Science Museum until early 2024, and is free to visit. It’s an odd exhibition that it can be quite emotional for such a clinical display, as we’re reminded of the dark days when so many of us hid away at home terrified of the invisible killer lurking outside.

You can find the exhibition at the far end of the ground floor, next to the entrance to the IMAX cinema.

The vaccine that hasn’t stopped people catching or passing on the desease. What a great achievement. If I took a polio vaccine I wouldn’t expect to get polio.

All hail the emperor’s new clothes.

If you took any medication expecting 100% protection, then you’re misinformed as no one has ever offered that.

But a medication that reduces the chances of catching an illness and the severity of the illness if you get it — is a very good thing indeed.

Perhaps best leave the science to the experts and stay in your seat typing away on the internet eh?

Covid vaccinations are estimated to have prevented 20 million premature deaths worldwide.

This will be a great exhibition, thanks for the update. I can remember my time as a volunteer on shift at the science museum vaccine centre with fond nostalgia. So many young folk queuing at the end of the day for surplus vaccines they weren’t yet scheduled for, make you realise that what people say on TV & online and the truth of peoples behaviour is rather different.