This Saturday (20th April) marks the centenary of one of the London Underground’s most impressive engineering feats. Despite thousands of people using it every day, hardly anyone ever gets to see it in its full glory.

This is Camden Junction, the massively complicated set of tunnels that linked the two branches of the Northern line and they carried their first passengers on 20th April 1924.

The junction owes its existence to a number of factors coming together around the same time, but the two main reasons were a project to enlarge the smaller tunnels on the Bank branch of the Northern line and extensions of the railway northwards from Camden. These two projects gave birth to the desire for a junction allowing Northern line trains to use either branch of the railway and cross between them.

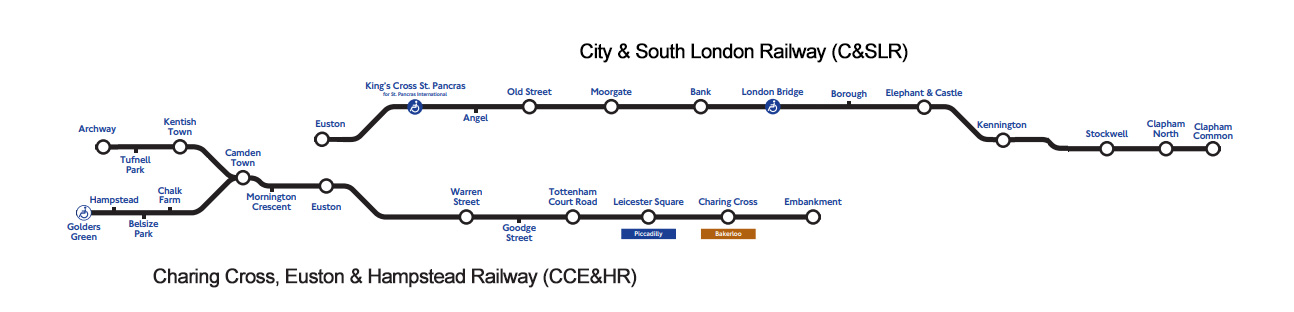

It helps to understand that the two branches of the Northern line were built by separate companies.

The older Bank branch was built by the City and South London Railway (C&SLR), while the Charing Cross branch was built by the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR).

In 1900, the Charing Cross branch — the CCE&HR — became part of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), controlled by American financier Charles Yerkes.

Later, in 1912, the older Bank branch railway company — the C&SLR — secured permission to enlarge its original smaller tunnels to the same size as the rest of the London Underground.

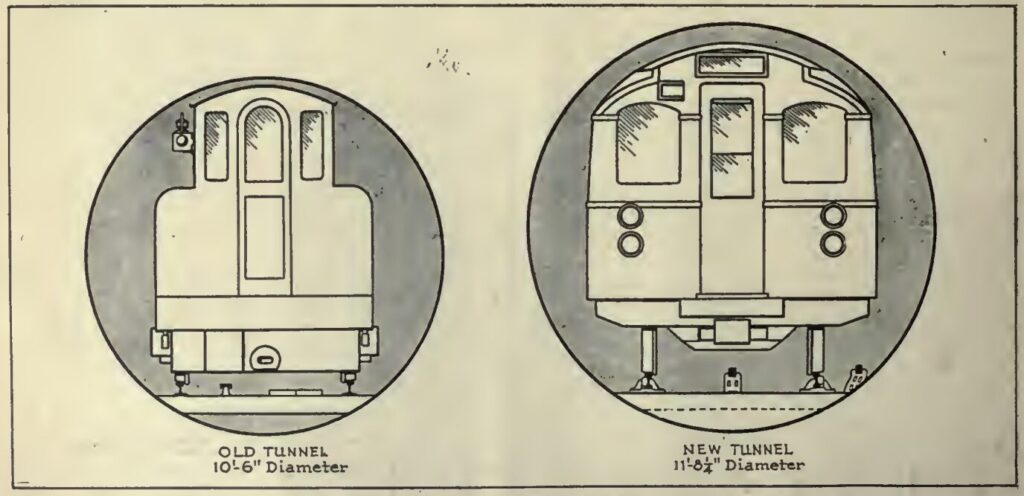

This was needed because the Bank branch of the Northern line had been built using tunnels that were 10 feet 6 inches in diameter[9], but later tube tunnels were built with a diameter of 11 feet 8 inches[1]. That meant the Bank Branch of the Northern line had to use smaller trains than the rest of the London Underground, and this was increasingly a problem for the railway company.

This was made worse by the fact that the older tunnels were also powered differently from the newer tunnels (earthed vs. isolated electrical returns), and they wanted to standardise everything to allow the sharing of trains between the tunnels and power supplies at their generating plants.

So, in 1912, the Bank branch railway secured permission for the upgrade.

At the same time, the owners of the Charing Cross branch were granted permission to build a junction at Camden to join the two railways together and allow trains to be shared between them.

At the time, it was expected that the two companies would remain separate — but a year later, Charles Yerkes was able to buy the Bank branch railway (and the Central line) and merge it into the larger Underground Railways company that he owned.

By the end of 1913, the London Electric Railway owned the Bakerloo, Central, Piccadilly, and both branches of the Northern line, along with the District line and the main London bus company. Only the Metropolitan line remained independent of an organisation that we would recognise today as the beginnings of a city-wide public transport network.

However, while plans were underway to upgrade the Northern line’s Bank branch and build a new junction at Camden, World War One broke out. As a result, it wasn’t until the 1920s that work could start, and the ambition to create a combined “northern line” was finally underway.

Prior to digging any holes, in June 1922, contracts for the new iron ring segments that would be needed for the tunnels were signed, with Derbyshire based Stanton Iron Works getting two-thirds of the work and Sheffield based United Steel picking up the rest.

The project to widen the older Bank branch tunnels officially started on 9th August 1922, when the tube line between Moorgate and Euston was closed, and they would have to work 24 hours a day on the rebuilding of the tunnels so that they would be ready for when the Camden Junction was opened — in April 1924.

Work on rebuilding the rest of the old tube line also started on 9 August 1922, but only after 8pm until 27th November 1923, when they closed the line completely until it was ready to fully reopen on 1 December 1924.

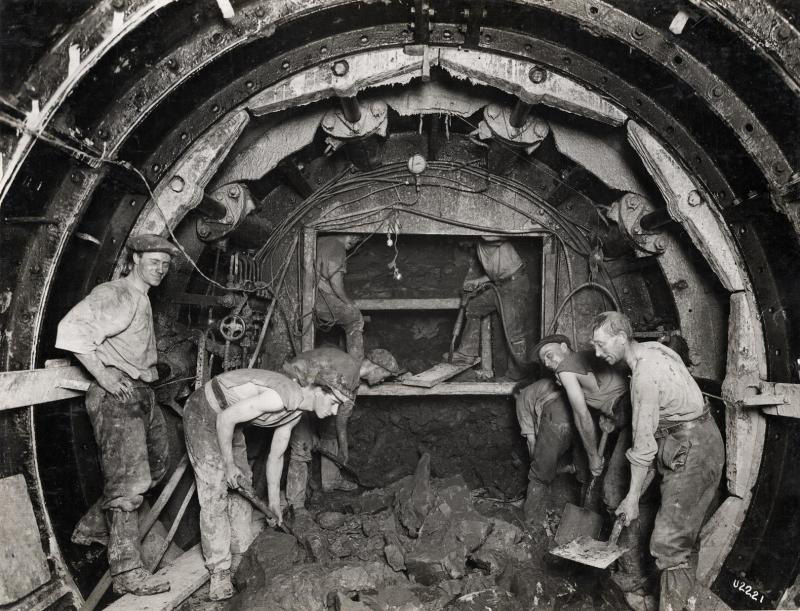

At the height of the rebuilding works, some 2,000 men[6] were working on-site at any one time. The expansion of the tunnels required removing the old tunnel rings, digging out the soil around them, and installing new rings in the wider space.

While the tube tunnel works were progressing, the railway company needed to start work on the Camden Junction.

Normally, if you join two railways together, you’d build a flat junction, with the tracks merging. If you do that in a tunnel, you just build a slightly larger tunnel around the new junction to allow trains to cross between them. For example, the Elizabeth line’s junction just to the east of Whitechapel where the line splits into two, is a simple railway junction in a large cavern.

However, for the Camden Junction, that wasn’t going to be possible because the two tube lines were already busy, and a wide set of several flat junctions wouldn’t be able to handle the number of trains passing across them — there simply wouldn’t be enough time between one train on one side crossing and another train on another side to also cross over to the other side.

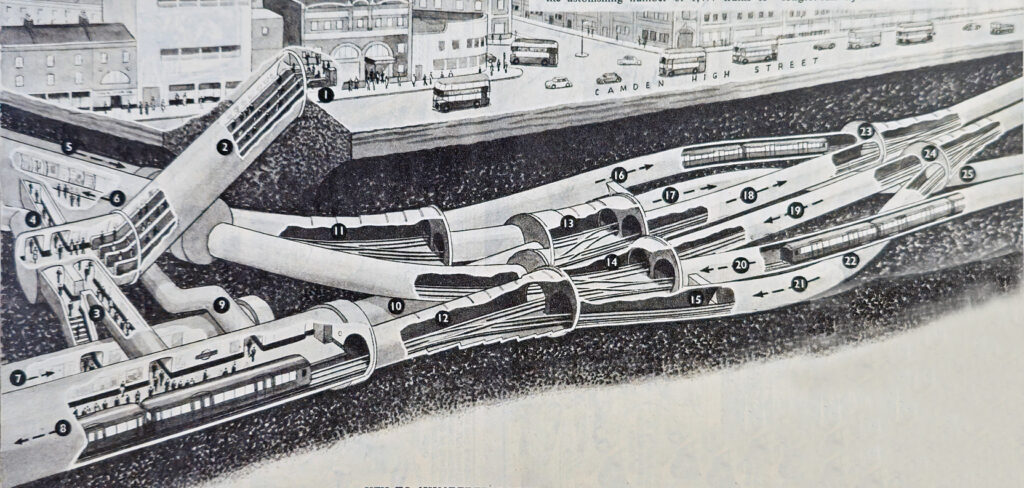

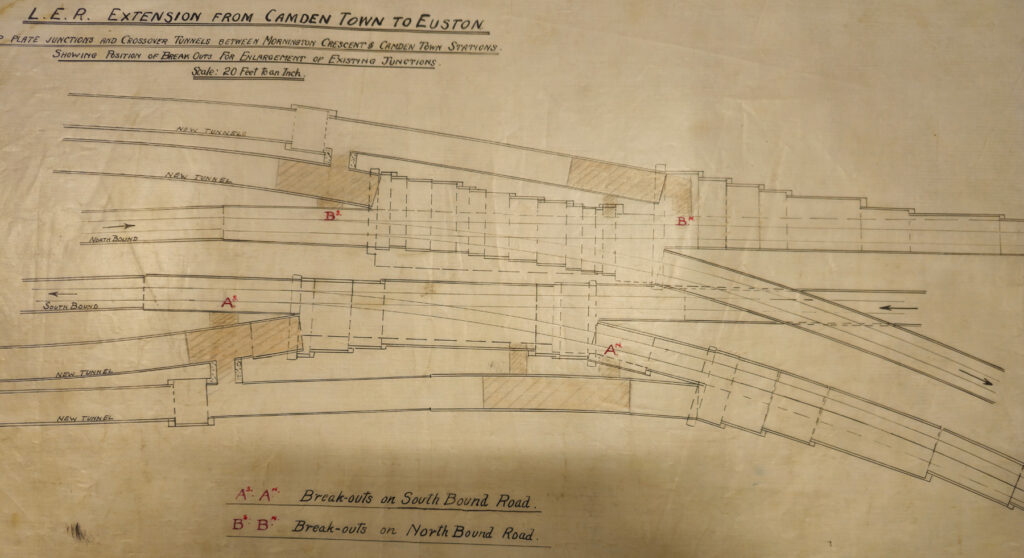

That is why they had to build a series of new tunnels that crossed over and under each other, expanding what had been two tube tunnels just south of Camden Town to six tunnels and six junctions.

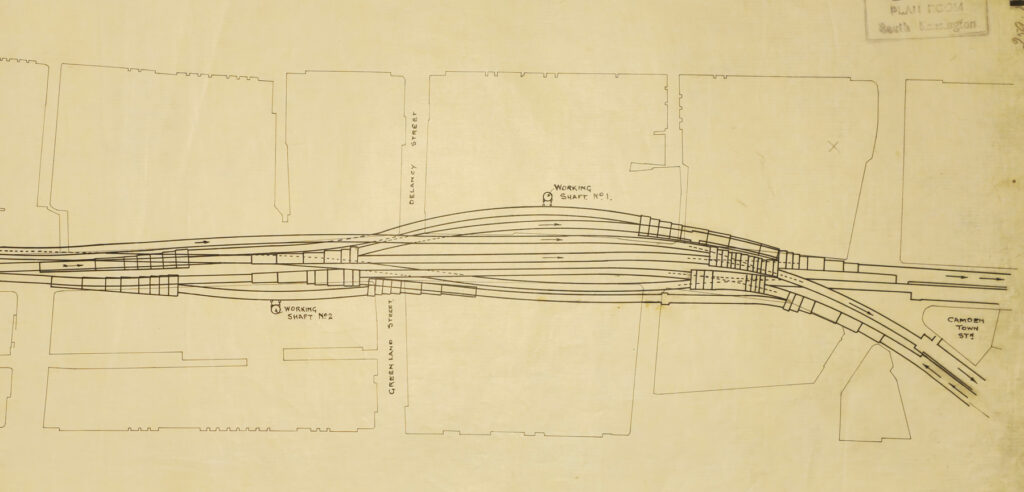

Building this exceptionally complex junction required a lot of work, and getting down to the tunnel depths required three shafts to be dug down from the street to the tunnels.

Two shafts were dug just outside the Camden Hippodrome (now Koko) next to Mornington Crescent station, slipping down between the existing Northern line tunnels. One shaft was dug down to 60 feet below the surface and was used to dig the new northbound tunnel, and the other shaft went deeper, to 80 feet below the streets, so that the new southbound tunnel could be dug.

The third shaft was dug at Ampthill Square and went even deeper, at 89 feet below street level. At this point, just one shaft was needed, as both of the new Northern line tunnels were at the same depth [7].

A map of the tunnels [11] seems also to show two smaller working tunnels, although it seems that the street names are incorrect on the map — as Greenland Street was actually Pratt Street.

During the tunnelling work, six Greathead shields were used to drive the tunnels forward, and some 80,000 tons of London clay had to be dug out by hand.

All this was going on while the Charing Cross branch trains were still running, although at the point where the new and old tunnels joined up, work was limited to evenings only.

In December 1923, the staff magazine[2] reported that the Northern line to Hendon was to cost over £500,000, while the total cost of the extension from Golders Green to Edgware, the new highway between Camden Town and Euston, the reconstruction of the City & South London Railway, and new rolling stock and car sheds would be over £5million. Nearly 200 carriages were being delivered, with the first going into service on the Hampstead line.

Mowlems had offered to concrete the tunnels, saying that they could do so for £10 per lineal mile — although when the contract was signed at the end of January, it ended up costing £40 per mile [8]. Soaring construction costs aren’t a new thing.

(There was also a rather peculiar argument in the archives about whether they should use British or Belgian cement. The decision isn’t recorded)

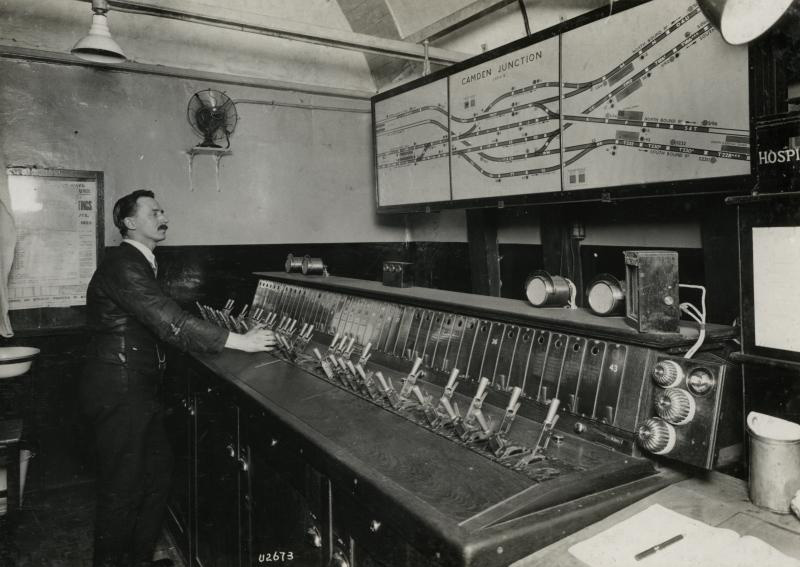

Part of the new junction came into use on 2nd March[10], but only for the still-running Charing Cross branch trains. On that day, the signalling for the new junction was also switched on, with the signals at Mornington Cresent also moved to the new Camden Junction control room.

Works were progressing well enough that later that same month[3], Lord Ashfield was able to give a speech where he confirmed the Camden junction was on target to open the following month. Along with the later extensions to Edgware and Morden, he said that these projects would “bring to a conclusion a period of rapid expansion such as London has not experienced for many years”

The new signal box, based on the northbound Highgate platform, controlled the junction. With 43 levers, it was described at the time [7] as the largest of its time in the British Isles. It was also said to be remarkable because the signallers had no way of seeing the railway they controlled.

Prior to opening the junction, they had to carry out safety checks. A report by Major G.L. Hall (sent on 26th April 1924) said that emergency braking of a test train showed that it could be brought to a stop within 350 feet, well within the 573 feet of the overrun allowed.

Another report by the same Major G.L Hall on 15th April recommending that the railway junction be authorised to open said that “the whole of the construction and the permanent way is sound and substantial and there is no indication of any weakness or fault in any of the tunnels.”

Today, 100 years ago, on 16th April 1924, the Minister of Transport approved “the use of the new line in question for passenger traffic”.

On Sunday 20th April 1924 – the junction opened.

A month after it opened, the staff magazine[4] reporting on the Easter weekend traffic said that the public had “quickly discovered the advantages of the Moorgate and Camden Town Tube, which enabled many thousands to reach the Heath by a new direct route”

By June 1924, the new junctions were reported to be handling no less than 1,504 trains a day as against 1,080 in the old tunnels. The staff magazine [5] said that during rush hour, the junctions handled 96 trains an hour, or a train every 37 seconds, and it has “now become one of the most important strategical points on the system.”

The Camden Junction also gave rise later to one of the more famous cut-away drawings to ever appear in Eagle comics – this one by Leslie Ashwell Wood, which was first published in October 1950 and updated in January 1967.

So this Saturday, 20th April 2024, the Camden Junction will celebrate its centenary.

Sources:

1] T.O.T. Staff Magazine, October 1922

2] T.O.T. Staff Magazine, December 1923

3] T.O.T. Staff Magazine, March 1924

4] T.O.T. Staff Magazine, May 1924

5] T.O.T. Staff Magazine, June 1924

6] The Railway Magazine January 1925

7] The Railway Magazine June 1924

8] TfL corporate archives – LT 454/6

9] Electric Railway Journal Vol. 65, No. 4 24th January 1925

10] LT Museum archives – 1998/96128

11] LT Museum archives – 1998/91965

LT Museum photos:

Camden Junctions signal cabin at Camden Town station by Topical Press, May 1924

Tunnelling work south of the Camden Junction by Topical Press, Oct 1923

Mornington Crescent Underground station, by Topical Press, 1922

Work on the Northern Line using the Greathead Shield, Topical Press, 1923

This fantastic feat was accomplished apparently without needing to close the station or lines (apart from where they were physically rebuilding the tunnels on the Moorgate side), which contrasts with the current rather cynical situation where TFL simply closes stations — or whole lines — for months on end, for their own convenience, and passengers and local businesses can just lump it.

Possibly related to new attitudes towards risk management and worker safety

Fascinating and well-reseached.

By the way, what happened to Oval on the diagram?

And Embankment shouldn’t be there – it wasn’t opened until 1914.

The junctions really are amazing!

Just looking at the drawing for more than a few minutes makes my mind boggle, so kudos to Leslie Ashwell Wood for doing it in the first place, never mind the astonishing minds who even conceived the junction to start with!

There was talk a few years ago about redesigning this junction once again to enable the splitting of the Northern Line into two lines once again. Sadly, this was shelved due to funding. I wonder if we’ll ever see something like this again? Perhaps to enlarge tunnels again to make way for a quieter and more enjoyable journey like on the Elizabeth line trains.

To clarify if I may.

Splitting the Northern line service does not need the 1924 tunnel junctions to be redesigned.

What it does need is for the station itself to be redesigned and enlarged to cater for the extra interchange traffic, including provision of direct step-free passages between the two southbound platforms.

Even if the line is not split, it needs to be enlarged to properly cater for the very heavy exit / entry traffic generated by the Camden markets, which is way beyond what the 1924 station was designed to handle.

All this was to be addressed by a reconstruction proposed around (I think) 2010. This involved driving a shaft for new escalators up to an additional surface building in Buck Street, all to be funded by property development. However this scheme failed to get planning permission.

I gather a revised scheme was prepared but is now on the back burner for lack of funding.

Nice historical context as well as the ever-fascinating illistrations. What’s so good about the design is that it’s the simplest possible general answer – two pairs come from either end, so there must be one split and one join on each track, with a short piece to link the two (repeated for the other track). The neat part is the way all the lines twist together to get the height clearance in a compact layout. Clearly got it right in that it’s still in use as built (although unfortunately they omitted a viewing gallery so it’s hard to see much). That said, in modern metro design any such complexity is avoided – hence the talk of permanently separating the Hampstead and Highgate operations, just as the Battersea extension has allowed at Kennington.

Ian doesn’t say, but the drawing of Camden Town was originally published in The Eagle: such was the quality of boys’ comics in the old days!

Ian did say it – in the pentultimate paragraph, and also paid a hefty licensing fee for the rights to use the image.

Great illustrated article. Most users including myself are so unaware of how the Underground was originally designed and built, and upgraded, and by whom, so this article is very much appreciated. The images are excellently selected. Who would have thought that the Eagle comic would prepare such amazing illustrations rather than the designers.

What a fascinating read. I had no idea the CSLR tunnels and trains were originally smaller and had to be enlarged. Was this smaller gauge the same as the Clockwork Orange in Glasgow?

“Ian did say it – in the pentultimate paragraph, and also paid a hefty licensing fee for the rights to use the image.”

My apologies, I don’t know how I missed that.

What a great article, well done. But it’s a pity that there aren’t any events, guided tours, lectures etc to mark the anniversary on the 20th.

Thanks for the fascinating article.I really like this sort of stuff, especially with intricate drawings.

The Eagle diagram is, indeed, impressive but must take advantage of artist’s licence to fit everything in. Before escalators, the original lifts dropped straight down from the existing top station to the south end of the platforms. That wouldn’t fit in the Eagle diagram!

And below all this are the two, widely spaced, 16ft 6ins diameter World War Two shelter tunnels which run for 1600 ft under Camden Town tube station and the junction tunnels. More challenge for an illustrator…

Those were designed to be available for a future Northern Line relief express railway which was intended to have been non-stop from Golders Green to Tottenham Court Road. The WW2 shelter tunnels at Belsize Park and Goodge Street were part of the same scheme.

Good to celebrate this extraordinary engineering feat, even if ‘my’ line does still annoy me much of the time. Despite using it daily I was still confused when I missed my stop a while back and had to come back and change at Camden but was of course doing so from the ‘wrong’ origination point… That said Euston is to my mind more unfriendly though of course that was originally two completely separate stations dozens of meters apart. The Victoria Line works there added to that but are an example of yet more ‘hidden’ genius with the same-direction, cross-platform interchange that was a feature of the line (more at my site: https://www.chrismrogers.net/designwhiteheatlondon)

Excellent explanation, and I hadn’t seen those plans before. Very interesting.

The Underground Group did buy the CSLR and CLR in 1913, but it wasn’t Yerkes that did it. He had died in 1905, before any of his deep-level tube projects had opened.

Fascinating article, thanks Ian. I’m not sure if it was here or somewhere else where I read that signallers from the Paris metro came to observe operations at this junction, seemingly puzzled that such a complex operation actually works so well.