Almost any classic image of Victorian London requires fog, the concealer of cheap film sets that wafts atmospherically around people as they carry out their nefarious deeds.

And now, the Charles Dickens Museum is taking a look at how the man himself turned fog into a critical character within his own novels, but also how he lived with the London fog that eventually drove him out of London.

What we, and the exhibition calls fog though wasn’t fog. It wasn’t the pleasing billows of white mist that delights us on a cold winter’s morning. London’s fog was smog — it was pollution. Caused mostly by homes burning coal, it despoiled the land, ruined furniture, stank abominably, and it killed in the thousands.

In 1865, Dickens described in Our Mutual Friend just how London’s fog was so very different from what we see today…

It was a foggy day in London, and the fog was heavy and dark… Even in the surrounding country it was a foggy day, but there the fog was grey, whereas in London it was, at about the boundary line, dark yellow, and a little within it brown, and then browner, and then browner, until at the heart of the City – which call Saint Mary Axe – it was rusty-black.

The exhibition looks both at how Dickens wrote about the fog, and how he lived with it. An item that will be almost familiar today, if in concept than appearance is a facemask — although in Victorian times it was delicate lace, and to stop people from breathing in the smog.

Elsewhere you’ll learn that the glass bell jars placed over objects, often clocks, in homes to keep them clean and protect them from clumsy hands are a Victorian invention to deal with smog — to stop it from damaging the item inside.

The exhibition is, unsurprisingly for an author, mostly about his writing.

As Dickens wrote in the opening of Bleak House in 1853, using the fog as a metaphor for the legal obfuscation caused by the Court of Chancery…

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards, and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats…[and] at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

The fog that, as Dickens subeditor wails, had got into a laundry and so spoiled the white fabric as to render it unsaleable.

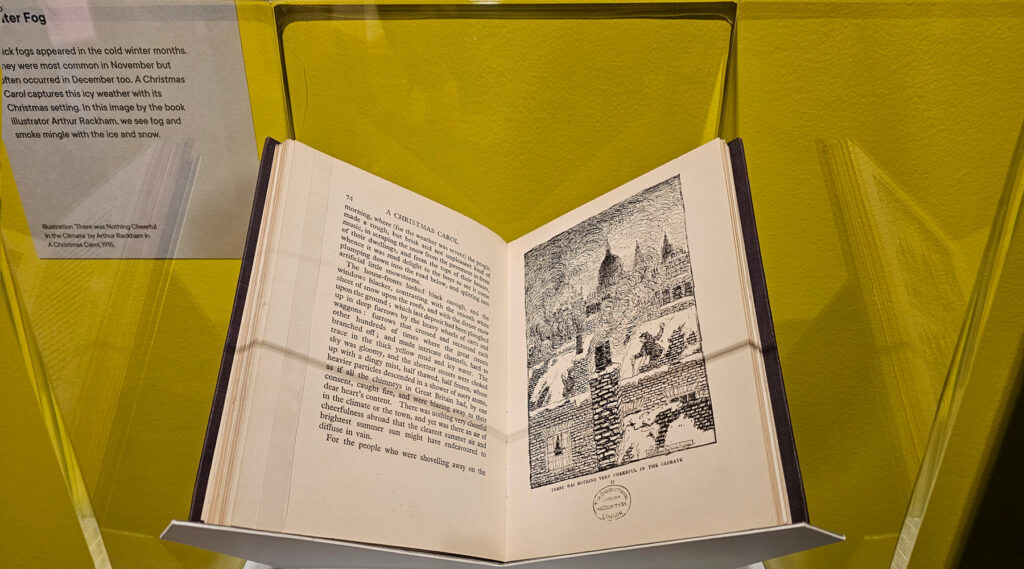

The smog, a term not actually used until 1902, but correct for what Londoners endured was also a metaphor for life – such as the absence of smog on Christmas morning when a renewed Scrooge opened his windows after that dread night.

Charles Dickens eventually moved his family out of London to get away from the fogs, and often write about how the cross atop St Paul’s Cathedral could be seen shining above the low-lying murky fogs, and was a landmark as he approached the city.

The exhibition also traces the many attempts by the government to get rid of the fog, culminating eventually in the Clean Air Act of 1956 — yes, as recently as 1956.

It’s a good collection of books and offers an insight into how badly society was affected by pollution and a reminder that the decorative London fogs of Sherlock Holmes and Dickens novels were a killer.

It would have been nice to have some jars filled with London fog to sniff and get a tangible connection with the air that our fairly recent ancestors breathed.

The exhibition, A Great and Dirty City: Dickens and the London Fog is at the Charles Dickens Museum until 22nd October 2023, closing just as the more modern decorative fogs return to the city.

Adult: £13.13 | Children (6-16): £7.88 | Concessions: £11.03

You can turn up on the day, but are recommended to book tickets in advance from here to ensure entry.

Extraordinary, really, that something was done about air quality in London only after thousands of deaths were caused by the sooty and sulphurous Great Smog of December 1952. Not even a year into the second Elizabethan age.

I wonder if, paralleling the modern controversy about ULEZ expansion, there were complaints at the time about the high cost of smokeless fuels, and the damage that environmental regulation may cause to London’s commerce and industry …

Maybe future generations will look back at the 1.3 million people killed by motorists every year in the same way.