Thirty years ago, on Sunday 3rd April 1994, the very first £10 penalty fare was issued to a fare dodger on the London Underground.

Before the penalty fare was introduced, all a person had to do was offer to pay the difference between the ticket they had and the one they needed to have — which is why stations used to have an “Excess Fares” window in the ticket hall to serve customers. Of course, not everyone paid, and when the penalty fare was introduced, London Underground estimated it was losing around £30 million a year, or about 5 percent of its revenue, to fare dodgers.

The launch of the penalty fare was announced in January 1994, coming into effect on 4th April, and at the launch, London Transport’s Nick Agnew said that “our aim is not to catch people and force them to pay a penalty. It is to encourage them to pay the correct fare in the first place”.

To put the losses into context, the newspapers reported at the time that eliminating fare dodging could refurbish 20 tube stations, or buy four of the recently announced 1993 version of the Crossrail trains.

In addition to the £10 penalty fare, which isn’t technically a fine or a criminal penalty — there was the potential for a court case which would lead to a criminal fine of up to £1,000 for persistant offenders.

“If a fare-dodger is believed to be regularly or maliciously defrauding London Underground, he or she could end up with a £1,000 fine or a jail sentence”, an LU spokesperson warned at the time the penalty fare was introduced, adding that “People come up with the most feeble excuses. They certainly won’t get away with them after April 3”

London Underground also announced plans for a £10 million investment in ticket machines to reduce fare fraud and also introduced the option to buy a fare-extension ticket before travelling.

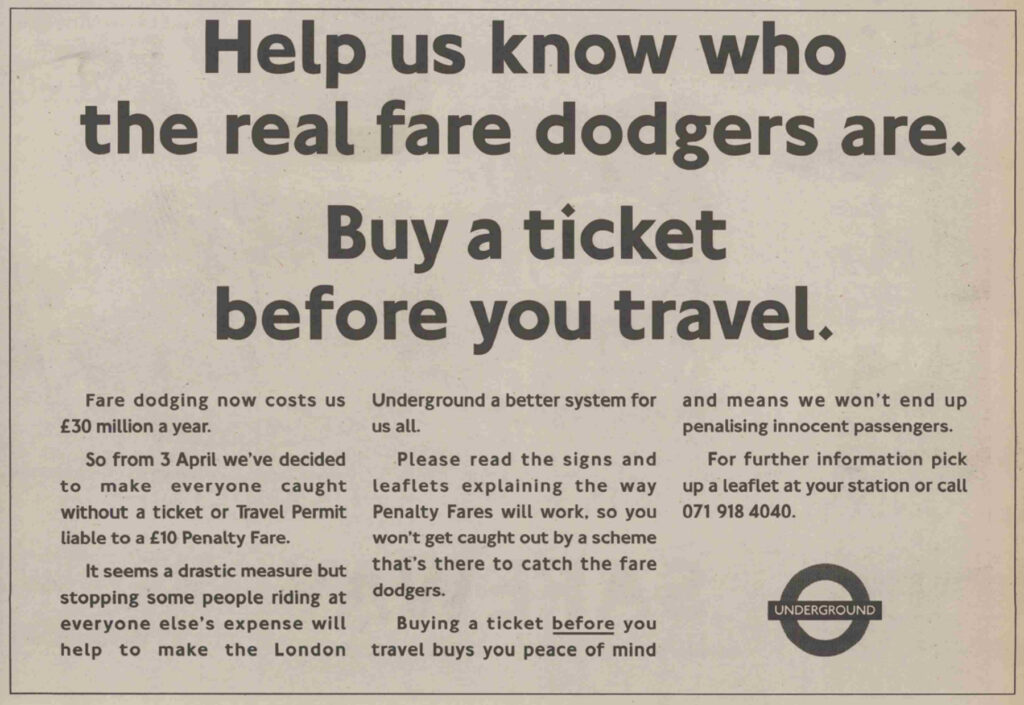

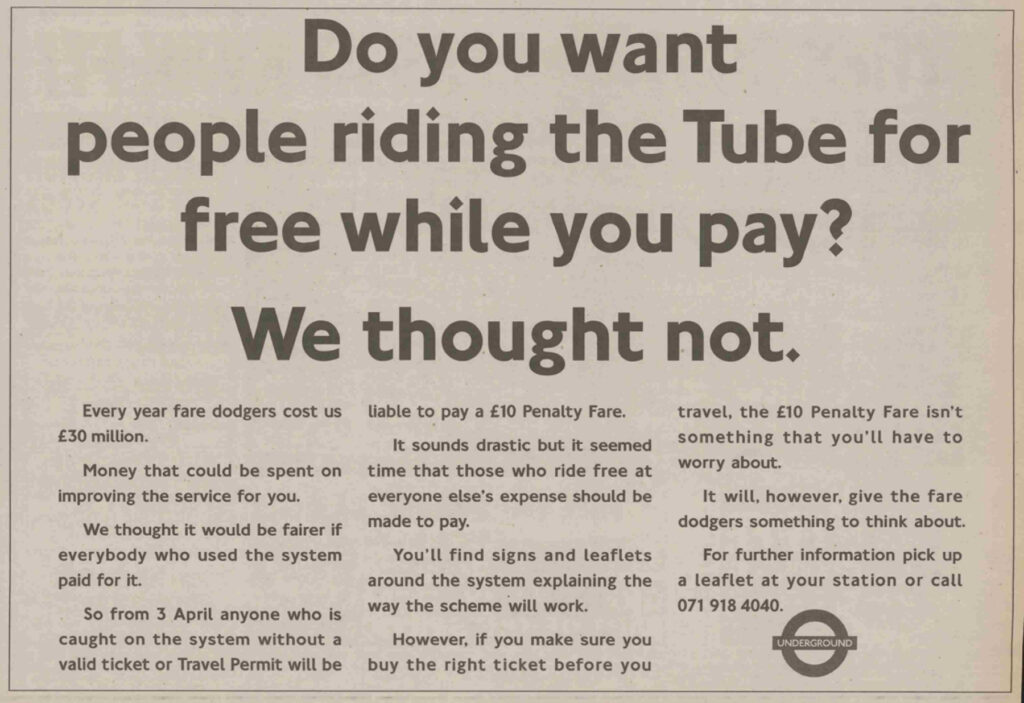

Ahead of the penalty fares coming into effect, there was a publicity blitz with posters in stations, inside tube trains, adverts in newspapers, and even a travelling roadshow that visited stations to explain what was changing.

Although ticket sales rose everywhere, it was reported that the number of passengers buying a ticket at Ruislip Gardens jumped by 24 percent. And that wasn’t even the biggest jump seen on the Underground. Sleepy little Roding Valley tube station topped the league.

The introduction of the penalty fare wasn’t entirely without problems, although most of them tended to be caused by forgetful passengers complaining loudly that their forgetfulness wasn’t justification for being penalised.

A year after the penalty fare was introduced, complaints to the London Regional Passengers Committee had jumped by a quarter over the previous year, mostly regarding penalty fares.

At the time, British Rail had an “amnesiacs clause” that would let a season ticket holder claim a refund on the penalty fare up to twice a year to accommodate forgetful passengers. London Underground refused to introduce a similar system, and an LU spokesperson responded that “It remains LU’s strongly held conviction that passengers should be in possession of a valid ticket before they start their journey.”

According to issue 438 of the staff magazine, LT News, when the penalty fare scheme on the Underground was launched, LUL estimated that about £6 million extra would be raised each year – not as a result of forcing the £10 penalty out of Tube travellers but through a significant reduction in fraud.

Despite the complaints, a year later, London Transport estimated that they had cut fare dodging from £30 million to £23 million and announced that it would introduce a £5 penalty fare on buses as well. Just two years after the penalty fare had been introduced, London Transport was estimating that the losses from fare dodgers had fallen to around £20 million.

An unexpected side effect of the penalty fare, though, is the now semi-regular TV shows where they follow the ticket inspectors around the tube, offering TV viewers the schadenfreude of watching people trying to evade paying and getting caught anyway. The first was broadcast just two years after the penalty fare was launched — on Channel 4 in April 1996, where they followed a squad of ticket inspectors and transport police blitzing the “notorious” Hammersmith and City line.

Fare dodging will likely never be fully solved. It is still estimated to be around 3 percent per year, and transport companies are always trying out new ways of reducing it further, just as fare dodgers come up with ever more ways of avoiding paying.

Of course, the penalty fare itself has changed over the years. If it had kept up with inflation, today it’d be just £20. It’s actually £100, reduced to £50 if paid within 21 days.

The value of the fine isn’t nearly as much important as its enforcement. These days fare dodging is absolutely normal in some parts of London, maybe 1/5 of passengers, and it isn’t surprising as I haven’t seen a fare protection patrol for many months.

If you’re saying that 20% of people aren’t paying, then that clearly isn’t in line with all the evidence.

And while you personally might not have seen a ticket inspector for months, many other people will have seen them, myself several times this year already.

I do feel the system is a symptom of railway decline. The growth of these penalty fares has coincided with a decline in ticket offices (the machines? Sometimes they don’t work, like all tech they’re fallible, or don’t sell the ticket you need). There is no incentive for companies to sell tickets, but severe penalties for the passenger who doesn’t. There is a definite presumption of guilt in the system, and some very aggressive inspectors (not all of them, agreed) and it’s just another way traveling by rail is unpleasant.

There’s no penalty if the ticket machine was broken at the station you started from. Then you just need to pay the value of the ticket.

Travelling by rail would be more unpleasant if there are no staff enforcing the rules than having barriers and tickets.

Most British people are puritans at heart and we insist on treating fare evasion as a moral issue when it isn’t. For example we are told that shoplifting costs other customers when there is absolutely no evidence. If shoplifting was reduced this would result in increased profits for the supermarket not lower prices.

I live in Berlin where there is a radically different attitude to fare collection. There are no ticket barriers at all and consequently no ticket collectors but there are teams of plain clothed revenue staff who can Levy on the spot fines if you don’t have a ticket. Travel regularly for in Berlin and you will encounter the revenue teams at least once a month often more often.

My question is how does Berlin compare to London ? Ticket barriers and staff are hugely expensive but no barriers at all probably means more evasion. But nobody would seriously think of putting ticket barriers at tram or bus stops. There are no barriers at DLR stations.

This isn’t a moral argument at all. It should be a question of balancing the cost of revenue control against the amount of fare evasion.

I’m theory you could put a ticket collector in every tube carriage and reduce evasion to zero but we wouldn’t because the cost would be prohibitive.

Do ticket barriers pay for themselves. Has anyone asked. Maybe ticket barriers are actually political posturing to prove we are tough on cheats. Do anyone know ?

“Do ticket barriers pay for themselves. Has anyone asked.” <-- yes, and yes. Read this: https://twitter.com/gceccles/status/1754145050299105744

On London Underground ticket gates also play an important part in controlling entry to stations to prevent overcrowding. Individual gates can be closed/reversed to ‘thin’ out the flow of people entering, or increase the number who can exit. As well as being able to be ‘plunged’ open to facilitate evacuation, the gates can also be instantly locked in ‘closed’ position to stop all entries if required. Having this flexibility to increase/decrease flows is far superior to the open/closed binary choice that the station entrance gates offer. Thinning out entry flows can keep stations open where they would have to close without that option, especially at busy stations. For that safety function it is unlikely London will see barrierless stations, at least not ‘Underground’.

Having been to Berlin on a number of occasions I can concur that you often see the revenue teams. The train had barely left Schonefeld Airport on my first visit when they boarded. I also got checked a couple of days later at Gesundbrunnen and a last time two days after that as I approached Oranienburg, near the zone limit for the Berlin ticket I had. Each time I saw them, I also saw them ‘catch’ someone. They seemed very efficient and it felt like trying to avoid a fare in Berlin was never going to be successful for very long.

I’m in Paris. The metro barrier in is very difficult to jump and the exit one impossible to. Tfl could retrofit polycarbonate extensions to help though it would be expensive.