Next Monday marks the 50th anniversary of when the UK changed over to a decimal currency — but not the London Underground — who for reasons, switched over a day earlier than the rest of the country.

But why, and what was the decimal currency switch?

In pre-decimal days, the UK’s currency was based on a system that had largely been around since Anglo-Saxon times, known as “pounds, shillings and pence”. Under this system, there were 12 pence in a shilling and 20 shillings, or 240 pence, in a pound.

Over time this was felt to be inconvenient.

The move to decimalisation in the UK started 200 years ago, in 1821 when a Parliamentary Committee was set up, although it eventually rejected the proposals. Various attempts were made to change the currency, but it was a report published in 1963 that set the stage for the UK to change its currency at last.

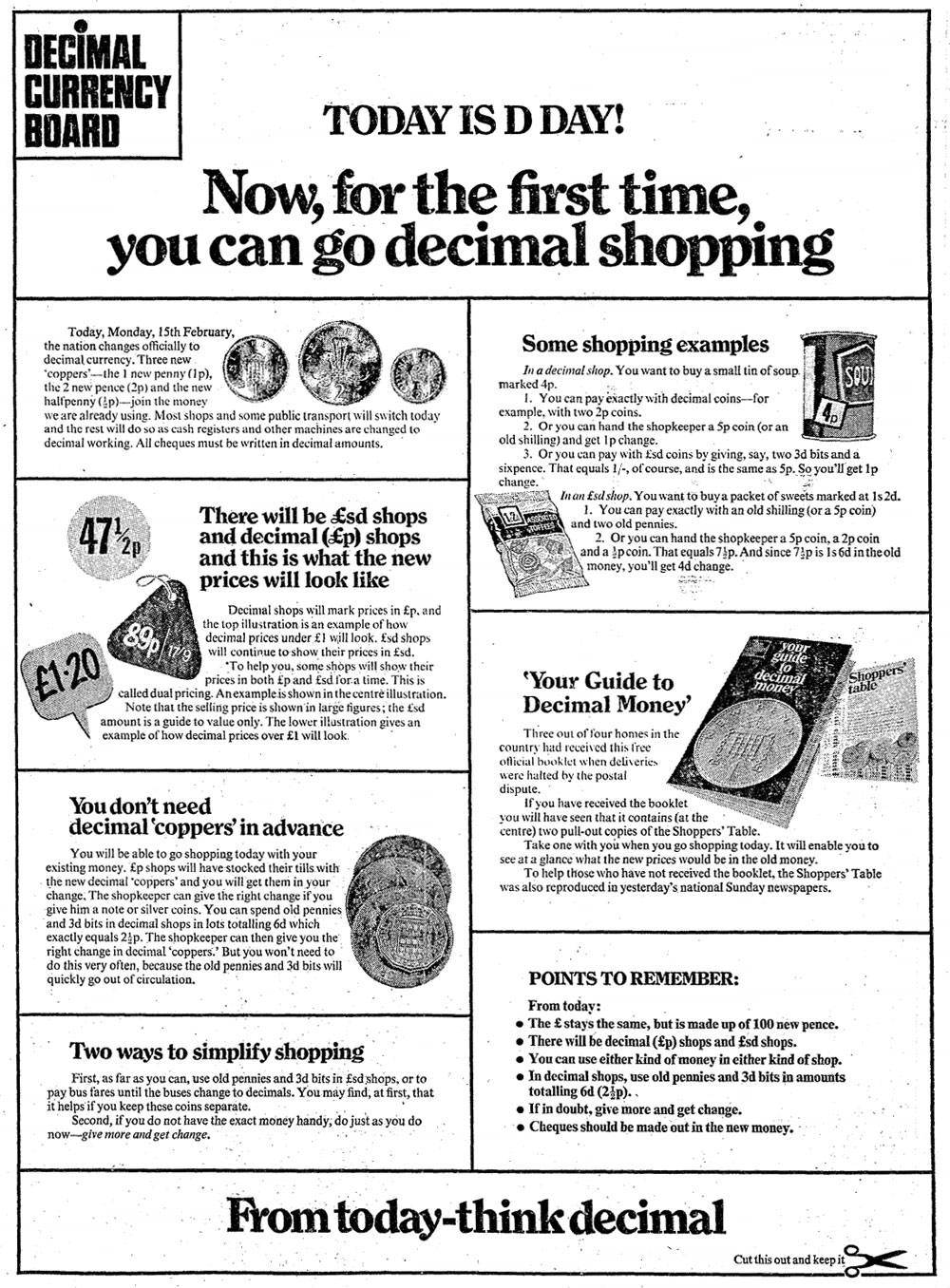

The plans for decimalisation would see the pound retained, as it was a global reserve currency at the time, but the shilling was to be abolished, and the pound subdivided into 100 “new pence” – each worth 2.4 old pence.

The penny was nearly called the cent, but that was dropped as it sounded too foreign to British consumers. It did mean the oddity of having old pence (d) being replaced with new pence (p).

Although there was a fixed deadline of 15th February 1971 for Decimal Day, in fact, the two currencies ran alongside each other for a couple of years. The new 5p and 10p coins were introduced in April 1968 to replace the shilling and florin coins, followed by the 50p coin in October 1969, replacing the 10 shilling banknote.

For many years, the 5p and 10p coins circulated with New Pence written on them, which doesn’t happen any more.

For a couple of years, shops showed two prices, in old currency and the new decimal currency to help people get used to the new system before it became mandatory.

To help, if that’s the right phrase, Max Bygraves released a song promoting decimalisation, which inexplicably was not a success in the pop music charts. Meanwhile, the government started its own massive education campaign with posters, booklets, and films.

Naturally, London Underground had to prepare as well for what it described in its staff magazine as “the massive problems the changeover will raise”.

A number of articles appeared in the staff magazines in the two years leading up to the currency swap, explaining how it was all going to work. The changeover wasn’t just a case of training staff across the entire of the London Transport network but also upgrading all the coin counting and ticket machines in the tube stations, and the handheld ticket machines used on buses. As with the shops, the tickets also had to be dual-currency for a couple of years, so they all needed to be changed — twice.

As reported in the London Transport Magazine1, there were also worries about the new 50p coin, as although it was designed to work with coin counting machines, it later turned out that none of the existing coin-counting machines could in fact handle it.

Not that many people were likely to use the 50p coin, it was worth the equivalent of £8 today, making it at the time the highest valued coin in circulation in the world.

Much hated at its launch, the 50p coin is now one of the favourites for collectors, so much so that although the 50p coin was released in 1969, it’s being used for a 1971 commemorative issue by the Royal Mint.

In addition, once a coin acceptor unit was developed to fit into their ticket existing machines, they then needed to be fitted to the machines – a laborious manual process for every single machine in London Transport. The works were carried out by London Transport’s ticket machine works based in Brixton. This was also where some 10,000 Gibson bus ticket machines were refitted to issue tickets in the new currency.

It cost £80,000 to convert the coin machines on the London Underground to decimal.

There was also the staff training to consider so that they weren’t as confused as customers during the transition. A number of training centres were set up in offices around London, and even mobile training centres in ten specially converted Routemaster buses.

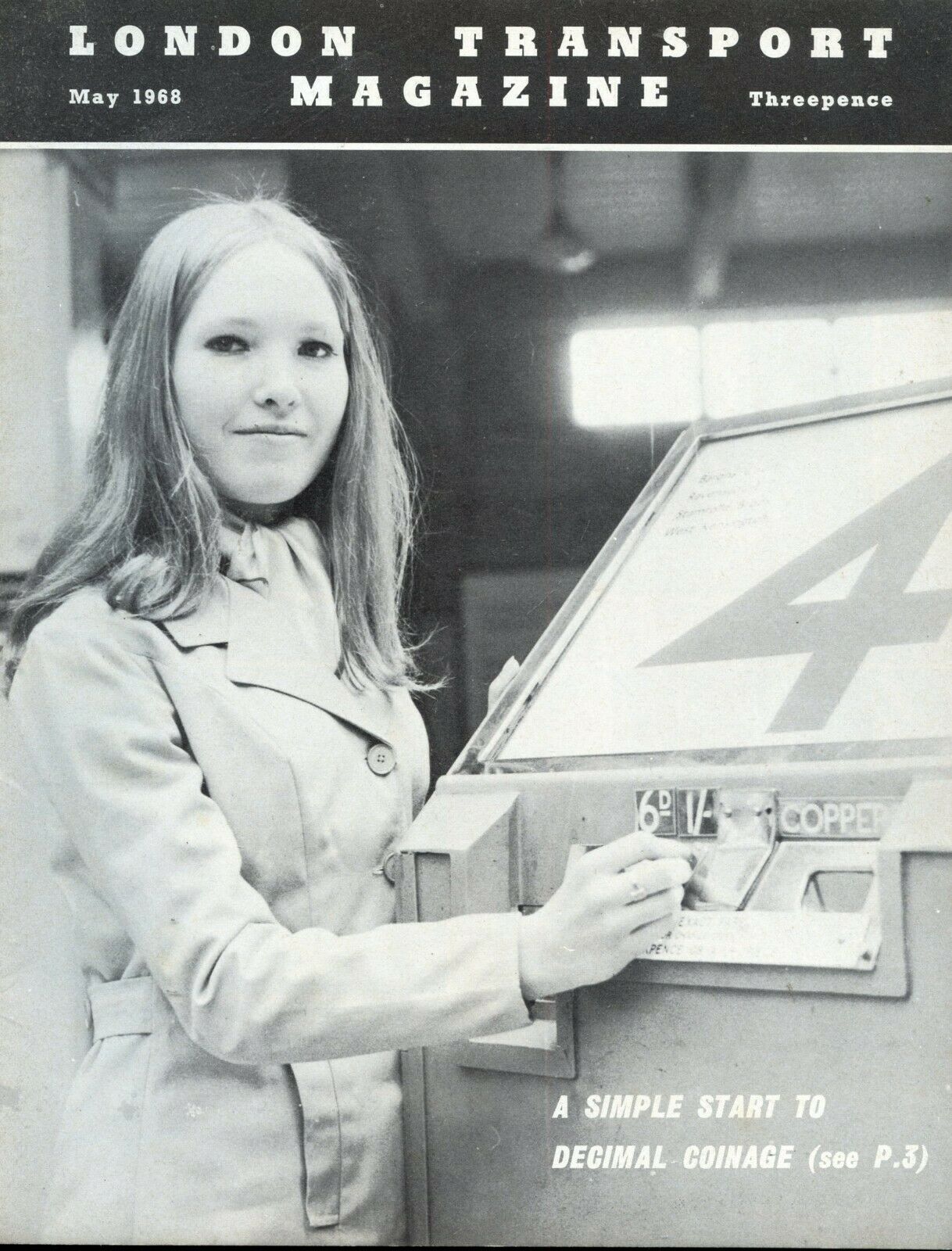

Just after the introduction of the “decimal twins”, the 5p and 10p coins in April 1968, the first person2 to use decimal coinage on the London Underground was 17-year old Miss Kay Bleasdale of Kensington in what was likely to be a publicity stunt at Hammersmith station, judging by the fact that a photographer just happened to be there to catch the moment.

For the record, she bought a fourpenny ticket, paying with a 5p coin, and getting a penny change.

However, the change in currency was also alleged to be a cover by retailers to raise prices during the confusion, and the London Transport found itself in the firing line due to a decision to fix all prices for the London Underground in 5 new pence increments.

So much so that in February 1970, the Chairman of London Transport, Sir Richard Way was forced to explain3 why they were using decimalisation to set all fares in 5p increments on the Underground.

The fuss was caused mainly by the fact that this would introduce a minimum fare of 5p at a time when it was still possible to buy fares for 6d (or 2½ new pence) for short trips on the Underground. Although less than 13 per cent of journeys were made on that fare, it was enough to cause a media fuss, especially at a time when people were worried that decimalisation was being used to sneak in price rises in shops as well.

Sir Richard Way noted the high cost of maintaining machines that took lots of different coins and that it would cost an estimated £1 million on top to include 1p and 2p coins in their automatic machine conversions. He said that the change to setting all fares in increments of 5p would simplify payments on the public transport network.

This was despite a government decision to retain the sixpenny coin ( 2½) in circulation until the end of 1973 (they remained legal tender until 1980!).

As an aside, the 5p fares increment still exists on TfL, and some of this year’s bus fares had to have high percentage rises because they rose by 5p.

Back 50 years though, and while the mechanical upgrades were being carried out, staff training was also being carried out. In the flesh, and through the internal staff magazine.

One of the articles in the staff magazines gave lessons on how to say the names of the new money. As noted4, rather than saying “two seventy five”, during the changeover period, staff were encouraged to say “Two pounds seventy-five new pence”

There were some odd quirks that seem very strange to us today. When writing out an amount, the decimal point was to be in the middle, not at the bottom, except when using a typewriter – thus £2·40 instead of the more usual today £2.40, and for some reason, use a hyphen instead of a dot when writing cheques, so £2-40.

During the final six months leading to D-Day, 22,000 cash handling staff at London Transport attended catch-up training classes.

In the few remaining months to the switchover, 750,000 posters were printed to warn people who might somehow still be unaware that all their money was changing, that it was about to do so. Also, 1,500,000 leaflets were sent to schools to educate schoolchildren about the new fares and coinage. People who used season tickets were also encouraged to renew early to avoid any problems on the first Monday when queues to buy tickets were expected to be longer than normal.

One of the problems that London Transport was most worried about in the run-up to Decimal Day was the retention of the old sixpenny coin.

The retention of the sixpenny came about due to its popularity with the public, and while decimalisation was generally welcomed, the scrapping of the sixpenny coin was not, and there were campaigns to keep it – which the government finally agreed to.

It was a bigger issue for London Transport, as its main fare on buses was six old pence – a sixpence coin – equivalent to 2½ new pennies.

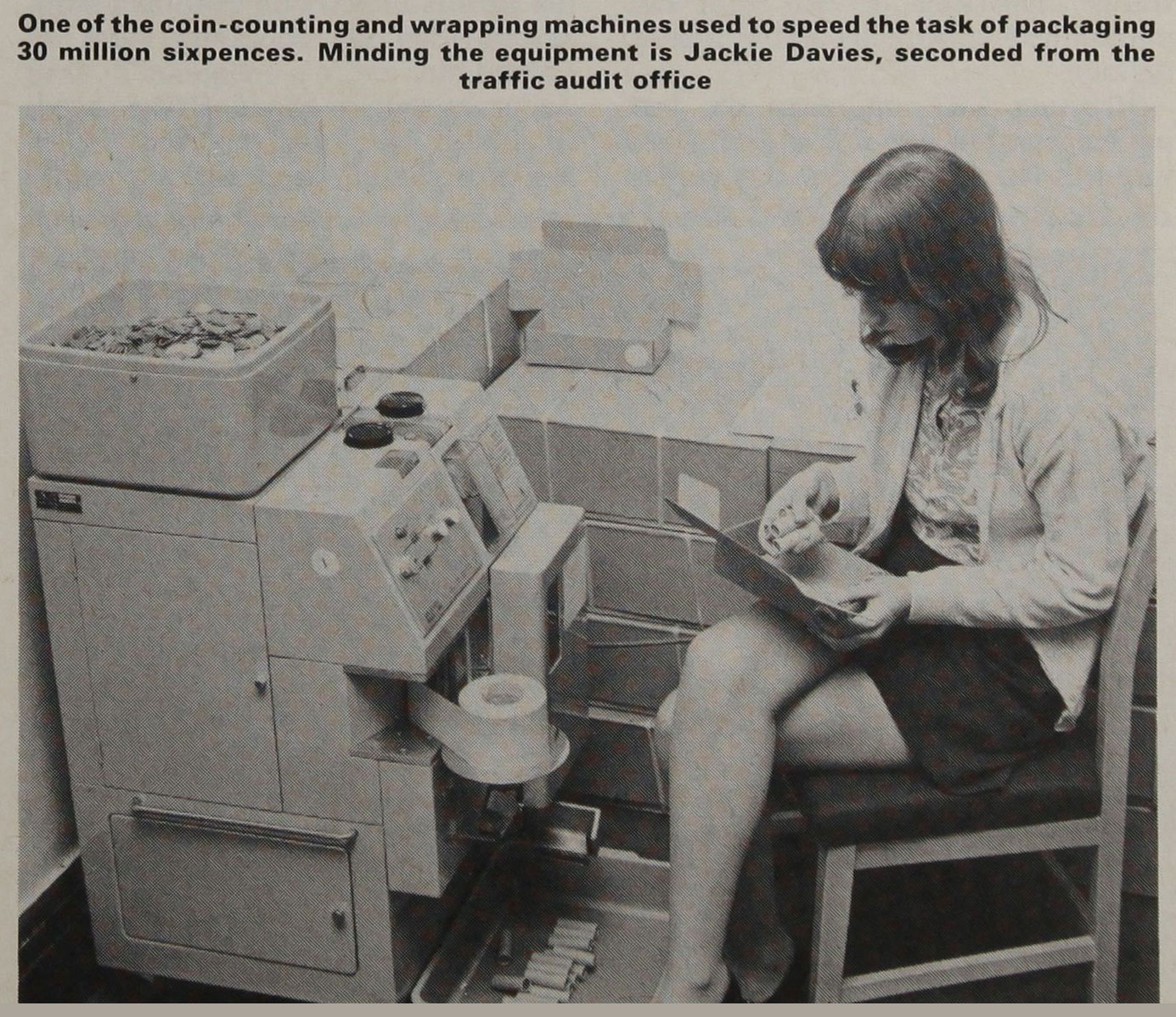

London Transport had agreed to keep accepting the sixpence for its own 2½p fare, but there was a risk that most shops would send any sixpences they have to the banks at the end of the day. That put London Transport in a situation where it might not have enough coins for giving change on the buses, so engaged in a huge effort to bag up as many coins as possible ahead of the switchover.

(This situation was resolved later in 1971 when they introduced5 a 3p minimum fare on buses to replace the 2½p fare)

But finally, D Day arrived – a day early.

The UK had long planned for the switchover to take place on Monday 15th February 1971, but the London Underground (and British Rail) switched over on Sunday 14th February instead6.

Remember, this was a time when it was still illegal for most shops to be open on Sundays, and as a result, the London Underground was very quiet with few people out socialising. That gave the railways an opportunity to start using decimal coins a day early so that staff would have some real-life experience ahead of the Monday morning rush hour.

The Lords Day became a trial for the machinations of Mammon.

As legally, the new ½p, 1p and 2p coins would not be legal tender (in the very narrow definition of what legal tender means) until the following day, the Underground ticket offices kept a supply of old coins for any fusspots who demanded the old coins.

And it went smoothly. OK, the toilet attendant in Piccadilly Circus tube station kept accepting the old coins, but the ticket offices reported minimal problems.

Lord Fiske, chairman of the Decimal Currency Board paid a PR visit to Euston Station in the morning, buying two tickets to Kilburn (10p) and a cup of British Rail tea for 4½p. One of the ticket office clerks, Jock Donald told The Times that the operation had been going without any trouble.

While the London Underground switched a day early, the buses switched over a week later, on 21st February. The delay7 meant that by the time the switchover took place on the buses there would be enough decimal coins in distribution so that conductors didn’t need to carry huge sacks of “new” coins to give out in change.

It wasn’t just the fares that the customers paid that needed changing. As with all firms at the time, invoices would need to be paid in the new currency, the payroll department had to swap over to paying wages in the new currency, and retired people needed their pensions changing.

And not even the internal staff magazine escaped – not only did it switch to decimal currency, but they also put the price up as well – to an eye-watering 2p an issue.

Overall though, years of planning at London Transport paid off and there were hardly any reports of problems when the Decimal Day finally arrived, even if it was a day early.

TfL corporate archive references

1) LT00030/076/00870

2) LT00030/076/00625

3) LT00030/076/00968

4) LT00030/075/00123

5) LT000030/076/01246

6) LT000030/076/01081

7) LT000030/076/01080

It was thought that using a hyphen instead of a dot on cheques would help prevent fraud, as the written amount tended to be ignored.

The use of the term D-Day caused loads of fuss as people still associated the term with the D-Day landings which were still fresh in the minds of elderly generations .

How apt you mention the toilets at Piccadilly Circus Station given they had a charge of 50p to use them last time I was there . Just think 50p that’s 10:shillings or 120 old pennies to spend a 1d which when decimalisation took place you say was equivalent to £8 !

There was a butcher’s shop in Exmouth Street Market , Islington who refused to go decimal and still had a price conversion chart on the wall many years after decimal currency was introduced!

Those who said it would increase prices have been proved correct especially if you convert today’s prices into old money !

What happens when you do the same comparison for prices as to your salary though – in real terms, most consumer prices have fallen over the years as a percentage of income.

The description of Miss Kay Bleasdale’s transaction in April 1968 is not right. Her 5p coin was the equivalent of a shilling, so she received not one new penny in change, but 8d in old money. (The new one penny coin, like the two penny and halfpenny coins, was not then in use).

Before D Day the replacement silver coins (5p, 10p and 50p) that were introduced from 1968 were usedq as the equivalent of 1s and 2s coins and of the 10 shilling note. The changeover took place, for the general population, on 15th February 1971 when for the first time you could spend the new bronze coins.

The changeover period, which the politicians expected would last eighteen months, took about six months and that was because shopkeepers had to give change in the new money, even if, as they were allowed to, they chose to carry on stating their prices in £sd as well as in pounds and new pence.

I’m not sure about London Transport, but conductor guards on BR had their ticket machines calibrated to pennies several weeks before D Day. The shillings were omitted (I’m not sure about the pounds – that would have been an expensive ticket). So a ticket for a 5/- fare bore “60” up until D Day and “25” afterwards.

There was also the staff training to consider so that they weren’t as confused as customers during the transition. A number of training centres were set up in offices around London, and even mobile training centres in ten specially converted Routemaster buses.

Forgot to mention the bus in the photo is an RT I believe Regent Type which was used mainly on central London buses but I remember how route 277 when converted from trolley bus route 677 used these buses instead of RM being one of the first conversions.

Thanks Ian, this is really interesting! Now I’m wondering why the pre-decimal pence was shortened to ‘d’ and not ‘p’?

I think it was “denarii” as in latin for pennies.

A very interesting article, thank you.

I was interested to note that about 2 years or so before decimalisation was inflicted upon us that the one pound bank note had printed I brackets I promise to pay the bearer on demand the some of One Pound (Twenty Shillings) which disappeared. This should have be a clue that decimalisation had already been decided before the public could have had a chance to oppose its inception.

I am 64 going on 65 and I loved the old currency. A pound could be neatly divided into three (six shillings and eight pence) I often fantasied that one day we would leave the Common Market and Decimal Currency and go back to Pounds, Shillings and Pence. Sadly just a dream!

The promise to pay declaration was a legacy of when the UK’s currency was tied to a commodity – in this situation the gold standard — and redemption of a banknote would be given in gold to the same value. We left the gold standard in 1931, switched to a fiat currency, so banks no longer offered commodities in exchange for currency – hence no need to issue a promise to pay the bearer on demand.

The fiat currency switch was nothing to do with decimalisation, as it occurred 40 years earlier.

I will be 55 this year. I love anything to do with Transport fascinating. Especially the old London buses.And also reading about the old decimalastion. I remember being at Nursery school at the time. This article brings back those happy times and good memories.

When I was at nursery school In Clapham South I remember being taught that there were 30 pennies in a half crown.

It didn’t seem quite as confusing at the time despite having pennies in both old and new money. The trick I think was to refer to “new pence” or just “pee”, and to drop the archaic composite “twopence”, “thruppence” and “sixpence” which could be ambiguous. I can still instantly convert between old and new as I was just the right age for it to sink in.

Me too. Every day… or at least when I used to get out!

An RT obviously, not a Routemaster RM used as the mobile training centre.

It was the advent of calculators that needed decimal currency without changing format between being used for currency and more general matters. Our mechanical calculator worked in pounds, shillings and pence which we used for checking dimensions on plans albeit with a notional 20-foot element.

Prices did rise against unfamiliarity and the penny unit 2.4 times what it had been, but not universally. The Amalfi in Old Curzon Street reduced the cost of a pizza from 5/6, 27.5p, to 27p.

On the day before D-Day (a Sunday) we spent the day riding on BR and using a Twin Rover on Underground. We visited various BR & LT outlets which had converted early. We collected lots of new currency (in coins) and surprised the local newsagent when we bought Monday’s sweets.