The diaries of Georgian Londoners have long suggested the city was a hotbed of vice and sex, but its becoming clearer just how widespread sexual diseases had become.

It’s being estimated now that as much as 20% of Londoners would have contracted syphilis by their mid-30s, and other illnesses such as gonorrhoea and chlamydia were even more prevalent.

London seems uniquely licentious, as while incidents in the city were far higher than would be found in rural areas, as is to be expected, even accounting for population, Londoners were twice as likely to be affected as the city of Chester, for which there are comparable records.

The revelations come from historians Professor Simon Szreter at the University of Cambridge, and Professor Kevin Siena at Canada’s Trent University, and published in the journal Economic History Review.

Cambridge’s Simon Szreter said: “It isn’t very surprising that London’s sexual culture differed from that of rural Britain in this period. But now it’s pretty clear that London was in a completely different league to even sizeable provincial cities like Chester.”

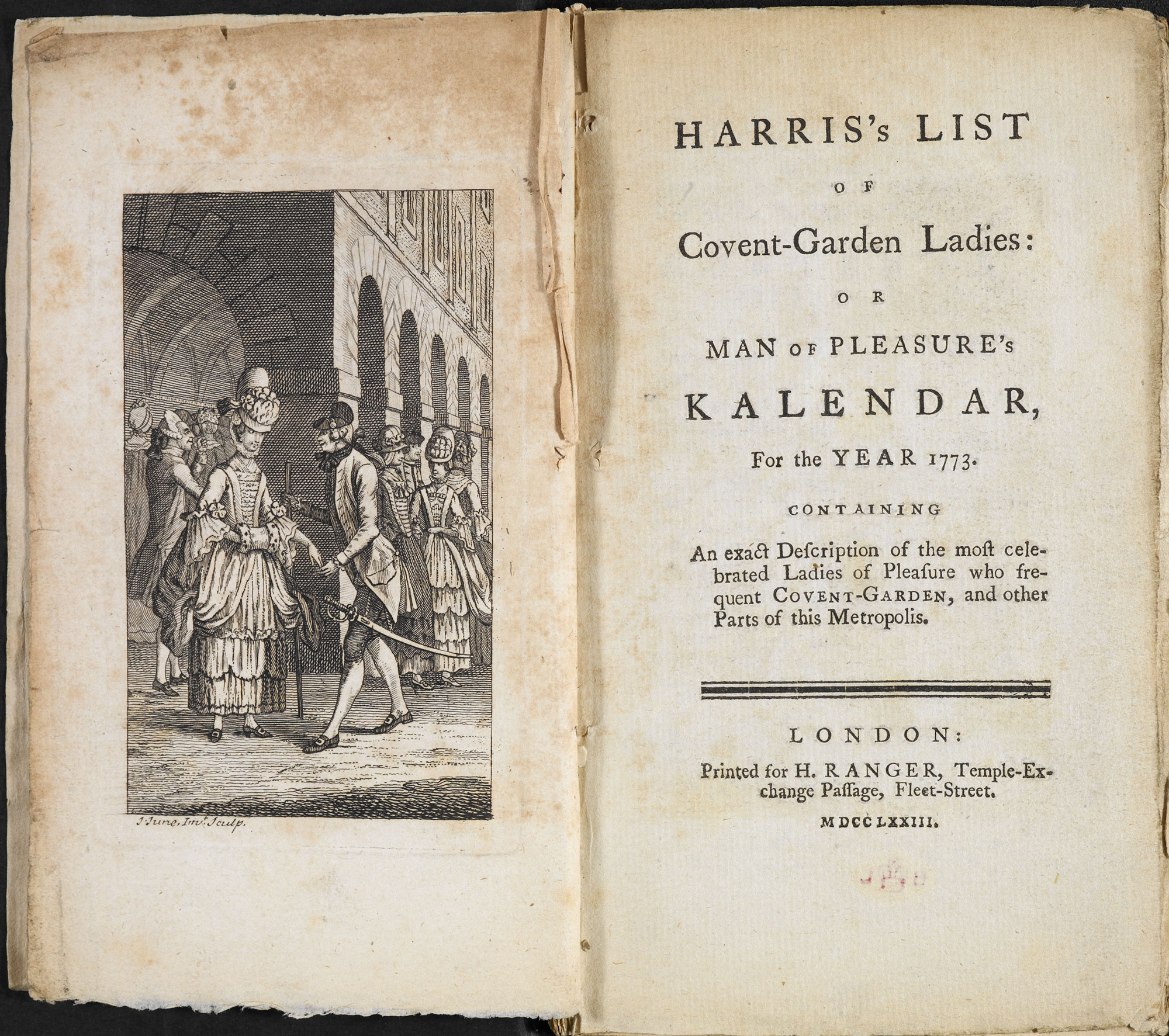

They may not have surprised James Boswell, the celebrated biographer of Samuel Johnson, who recorded up to 19 episodes of venereal disease in his diary between 1760 and 1786. Boswell left a candid record of his many sexual exploits with prostitutes in London in this period, as well as the pain caused by contracting STIs.

On experiencing initial signs of discomfort, such as a rash or pain in urination, most people in Georgian England hoped that they only had ‘the clap’ (gonorrhoea) rather than ‘the pox’ (syphilis), and would have begun by self-medicating with various pills and potions.

But for many, the symptoms got worse, leading to debilitating pain and fevers which they couldn’t ignore.

Mercury salivation treatment was considered a reliable and permanent cure for syphilis but it was debilitating and required at least five weeks of residential care. This was provided by London’s largest hospitals, at least two specialist hospitals, and many poor law infirmaries, as well as privately for those who could afford it.

The Martyrdom of Mercury. The scourge of Venus and Mercury, represented in a treatise of the venereal disease. John Sintelaer. 1709

The hospitals usually had dedicated spaces to deal with victims of the pox, known as “foul wards” away from other patients, for moral rather than medical reasons.

Patients in London’s foul wards often battled their diseases for six months or more before seeking hospitalization. This helped the researchers, making it highly likely that the majority of patients they were counting in the records were suffering from significant protracted symptoms more characteristic of secondary syphilis than of gonorrhoea, soft chancre, or chlamydia.

The researchers are confident that one-fifth represents a reliable minimum estimate.

Why was Georgian London so syphilitic?

The researcher suggests that a major factor could have been the increasing movement of people through London in this period, combined with the financial precarity experienced by young adults aged 15–34.

Young women were particularly well represented among new arrivals to the city, and they were often placed in positions of domestic and economic dependence on mostly male employers.

The historians emphasise that STIs were particularly rife among young, impoverished, mostly unmarried women, either using commercial sex to support themselves financially or in situations that rendered them vulnerable to sexual predation and assault like domestic service.

The Pox was also rife among two sets of men: poor in-migrant men, many still unmarried and on the margins of London’s economy; and, a range of more established men like James Boswell, who was able to pay for hospital or private treatment.

While the study is of lurid interest, it adds to the understandings about the causes of deaths in Georgian London, and also the impact on births impacted by STIs.

The study by S. Szreter & K. Siena is published here: The pox in Boswell’s London: an estimate of the extent of syphilis infection in the metropolis in the 1770s

Syphilis hasn’t gone away, in fact, it seems to be making a bit of a resurgence in recent years, and can still kill if not treated. London is still maintaining its Georgian reputation as a haven for the disease, with rates more than double the rest of the country, and accounts for nearly half of the entire UK’s cases of syphilis.

There is no vaccine.

At last a medical story not about oh what’s it called?

Thanks for reminding us that there is more than one disease to which we humans are susceptible.

Timely too what with pubs reopening, though how you do it whilst social distancing baffles me.