You might have seen a small round cubicle on the edge of Trafalgar Square. You might have been told it’s London’s (or the UK’s) smallest police station. You might even have been told that it was an idea by Sir Lionel Edwards, head of the Office of Works.

Both claims are wrong.

It has never been a police station. Never. Some more reputable publications will say it’s a police box, which is more accurate, but technically, it’s an observation box so that the police can keep an eye on Trafalgar Square.

In times past — it was felt necessary to keep a constant watch on the Square as it was used as a rallying point for political protests, and as those were often not announced in advance, the police needed to be able to summon help.

But how did they do that in the time before radio? Well, in the 19th century, the telegraph, then the telephone was invented, so the police started installing telephone boxes around the country.

One of them is rather famous.

Trafalgar Square didn’t get a blue box (except once), but in order to improve communications with the nearby police station, they installed a wooden telephone box, at the time known as a silence cabinet, next to the London Underground entrance.

It was a temporary thing, and from 1919 onwards, the police campaigned for a permanent installation, and in the end that became the famous “smallest police station”, a small box hollowed out of a former lampstand that stood on the spot.

But there are many myths about how it came to be built, and in fact, the truth is no less convoluted, so off to the original documents, which are stored at the National Archives.

For a start, many publications say that the suggestion to hollow out the lamp-stand and turn it into a police station came from Sir Lionel Edwards, head of the Office of Works.

The problem is that a cursory search will immediately reveal an issue with this claim… Sir Lionel Edwards doesn’t seem to exist. For a senior civil servant with a knighthood to leave no fingerprints in history is very odd indeed. So who came up with the idea?

There was a Sir Lionel Earle who was the permanent secretary to the Office of Works from 1912 until 1933, and the sort of person likely to be involved. So is this just a simple accident, that everyone has copied ever since?

The confusion by whoever was the original author of the mistake is however understandable, as many of the original documents were letters between the Office of Work’s Sir Lionel Earle and the Met Police’s Mr G Edwards OBE.

It seems that the two names were once accidentally merged, and the fictional Sir Lionel Edwards born, and everyone since then who has just copied/pasted the mistake and never thought to check the facts.

They will also say that the idea to hollow out the lamppost was his idea.

Well, sort of maybe. It certainly came from his department during very long and protracted negotiations with the police, but I doubt from the text of the letter proposing it, that it was his personal idea.

Let’s look at how a lampstand became a police box.

It all started in June 1919, when the Commissioner of the Police of the Metropolis expressed a desire for an “Observation Box with direct telephonic communication to Cannon Row Police Station” to be provided in Trafalgar Square, or its near vicinity.

In recent months it had been reported that police in the Square had difficulty securing support from the nearby police station when assistance was needed.

A few months later, after talks had evidently led nowhere, the Office of Works wrote that it would “feel the greatest reluctance” in permitting the erection of a telephone box in the Square.

The existing wooden police observation box was only permitted after the Board of Works had been assured that it was a necessity of war emergencies.

It’s worth noting that the police seemed to be after a free-standing police box that would have been somewhere in Trafalgar Square, so it would have been quite conspicuous, and hence the concern by the Office of Works was not unreasonable.

By that October, the Superintendent of Cannon Row Station wrote that the officials of the Office of Works had offered to allow a small cavity to be built into a wall to allow a phone to be installed, but the police were unhappy with that idea.

Negotiations with the Union Club (now Canada House) was amenable to putting a telephone near a window for the use of the police during demonstrations in the Square. A suggestion to use Admiralty House in a similar fashion was also made.

The wooden telephone box next to the tube station entrance was still there in 1921, so the temporary was by now semi-permanent, but the London Underground were planning their own refurbishment works, and needed it to be moved.

That June (1921), a clearly frustrated letter to “my dear Earle” from Sir William Horwood, Commissioner of the Police of the Metropolis complained that the Office of Works simply did not understand the situation faced by the police in dealing with — at the time — quite regular unauthorised protests in the Square.

The police were of the opinion that it was absolutely essential that they had an observation box to watch crowds assembling in Trafalgar Square and be able to summon reserves at short notice.

Responding to “my dear Horwood”, Sir Earle explained that the department, well, more particularly the boss of the department, Lord Peel, felt that the existing telephone box was an “exceptionally ignoble specimen of telephone apparatus”, and that several MPs agreed with him.

They wanted it removed. London Underground wanted it removed. Only the police wanted it kept. Sir Earle asked if an observation post on the roof of the National Gallery would suffice instead.

Not really came the reply.

Following riots in 1926 during the General Strike, a negotiated agreement was made to make the wooden telephone box a permanent granite box, and everyone was moderately happy. The police were negotiating to have it raised up a couple of feet so the policeman inside could see over the heads of crowds, and the London Underground was keen to put their maps on the back, even if the police were as equally keen that they didn’t.

November 1926

This is the breakthrough moment.

In a letter to Mr Edwards, Sir Earle said that “a brain wave has come to us”, proposing that it might be possible to get the telephone box inside the great granite base of the big lamps at the end of the balustrade around the Square.

Although he warned that the work involved in taking down the granite column and carving it out would be significant, he said that the advantages would that it would avoid an additional structure being added to the Square.

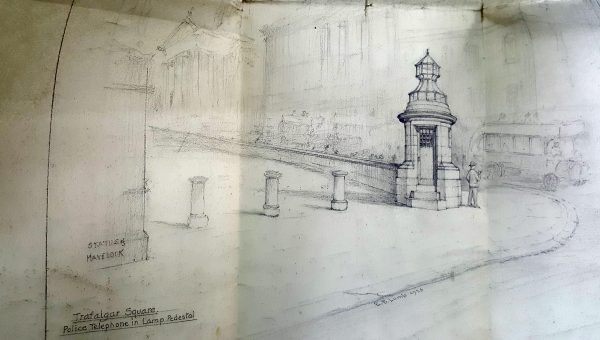

A few days later, the Met Police’s Mr Edwards replied noting that he had also thought of the same idea (oh really?), but had dismissed it as the solid appearance of the lampstand might be adversely affected and that its placement could mean an obscured view of Nelson’s Column due to the plinth holding the Havelock Statue being in the way.

But his main concern, who picks up the “substantial” extra costs of the proposal?

It seems that conversations must have been progressing though, as by the following March (1927), the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis was expressing his pleasure that this “somewhat long outstanding problem” had finally been resolved.

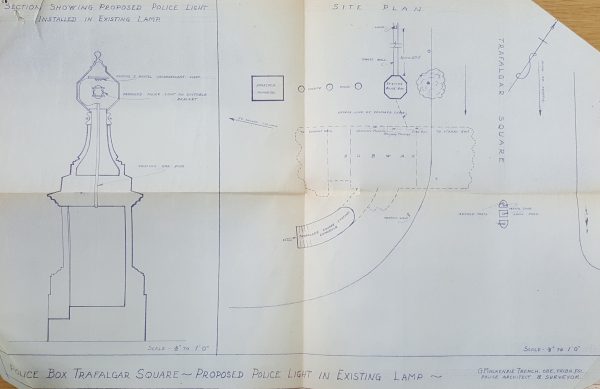

However, approval had been given for a freestanding telephone box, so the sudden change of plans to hollow out the lampstand was presented to the Permanent Under-Secretary of State at the Home Office, Sir John Anderson. A man who later was to become famous for the WW2 Anderson Shelter.

That July he approved the estimated £550 observation box, noting that the high cost was justified for the location.

By now though, the Royal Fine Arts Commission were now involved and getting a bit hot under the collar about the design of the box. Fortunately, their final suggestion to amend the eventual design as to put the door on the side facing into Trafalgar Square met with approval from the police.

You can see the early drawing here which shows the door facing the other direction

In November, a tender for the construction had been accepted, and construction works are now underway.

However, there was a problem with the idea of providing an electric light inside the telephone box. No electricity. The police approached both the local electricity company, the Charing Cross Electricity Supply, and the London Underground, but were unable to secure a connection.

As the external lamp was being lit by gas, it was decided that the interior one could also be lit by gas.

A slight snag the following month, as new granite needed for the telephone box had been dispatched by railway from Cornwall but then been stolen en-route to London.

Stealing from the police. Whatever next!

That mishap notwithstanding, works on the new telephone box were completed on 19th March 1928 and the keys were handed to the police. The old wooden telephone box was removed a few weeks later.

In the 1930s a modification was made so that the gas lamp above would be converted to electricity, and it would be controlled so that it blinked on and off when the telephone rang. It seemed that the police were often out patrolling the square and couldn’t hear the phone ringing from the other side. So now they had their own flashing alarm.

Since then it’s been serving as a police observation box right up to the 1970s when radio communications rendered it superfluous to demand.

But it’s still something that’s worth pointing out when passing, and now you can give the correct history of the “smallest police station” in London.

Sources:

National Archives references, MEPO 2/2604 and WORK 20/180.

So who owns it now?

The Queen – although the Mayor of London’s office does the day to day work in the Square.

Excellent research. Many thanks!

It’s actually used by the BBC and other journalists, if you look in there you will see that there are plug in points for broadcast journalists and ISDN points that can be used for quality audio.

It’s currently being used by builders, as it’s full of builders kit and bags of materials.

It was called the smallest police box in London back in the late fifties early sixties,when it appeared as somewhere to ‘spot’ in the I Spy-London book. I got points for that!!

Anybody else out there in Ianvisits land,old enough to remember I Spy books- they got you out and about.

I had one. They were revived, so you can get out and about filling one in again – I-spy London, current version here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/i-SPY-London-Collins-Michelin-Guides/dp/0008182892/

No more Big Chief I-Spy though.

I Was a young police officer there in the early 80’s came in handy for not only watching the square but keeping warm on freezing nights and having a crafty smoke. My own definition of a Police station would be a premises with a charging facility ie a desk and cells. At Wellington Arch just up the Road you could charge people but I cannot remember cells being there not in the 70;s or 80’s anyway.

I am doing a bit of research on this structure and would love to get in touch about your use of it in the 80s!

Interesting that such a small building had such a lengthy gestation. I wish I were around to have seen the flashing light on top; not just the other famous blue version then.

But what to tell my 6yr old Batman fan who’s convinced it’s a secret entrance to the Bat Cave?

I remember that when a child in the ’50s Wellington Arch was always pointed out to me as the ‘smallest police-station’.

Gather it is now a museum?

Yes, it’s been open to the public and run by English Heritage since 2001. Ian has covered many of the previous exhibitions there in the past

I am delighted that my namesake Sir William Horwood has finally got the recognition he deserves for this landmark! Fascinating! Ian (as always) you’ve done us proud!!… and before you ask, no he’s not a direct blood relation unfortunately. It’s complicated…

A round cubicle is also impossible! 😉

I have passed this loads of times without noticing it! Thanks for the insight. Really interesting. Keep them coming.

Thanks for that – a very comprehensive explanation to point people to in future. There is a smattering of other handy pages online debunking this long-running myth, but yours has set a standard that would be hard to beat.

On a related matter, some say it’s a myth that you are allowed to give any tour guide you hear spouting the police station thing a custard pie in the face – but it’s not, that one is on the statute books – a bloke in the pub said so. You can also do it for the lanterns in Trafalgar Sq coming from the Victory, Nancy’s steps, Nelson’s nose, the private forecourt that isn’t a drive-on-the-right public road, and a few others… 🙂

As well as Wellington Arch, Marble Arch also had a small area police officers could access, opened by the key issued to all constables with their whistle.

I have read somewhere that the special lamp shade on top was called a ‘Panopticon’ that gave out more light than if the shade was not present, thus defeating the laws of physics. There is a huge amount of ‘legend’ (i.e. total rubbish) surrounding this little London Delight. Thanks Ian for some real information, very handy for my next chat about peculiar bits of London.

A fantastic piece of investigative journalism! Keep up the good work.

But just a minor point if you’ll indulge me. A knight of the realm is normally referred to as Sir [full name] or Sir [first name], so Sir Lionel Earle or Sir Lionel but never Sir Earle (not this side of the Atlantic anyway).