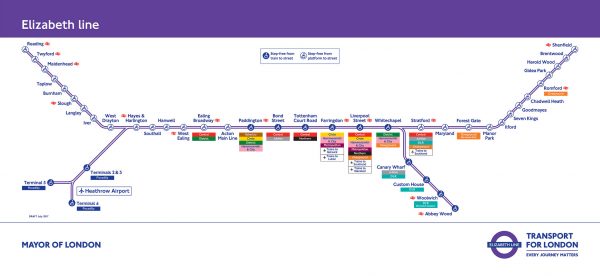

2018 will be the year that Crossrail is completed (Edit: well, that worked out well), and the Elizabeth line is born, yet it could have looked ever so different had previous plans been built.

It’s been a long time arriving, much longer than most realise…

When it launches on 9th December 2018, the Elizabeth line (nee Crossrail) will increase central London’s underground rail capacity by around 10 per cent. To put that into context, it’s equivalent to lengthening every tube train passing through central London by an additional carriage.

But the process of getting to 2018 has not been an easy one. The path was long, strewn with politics, spies, and debates about whether railways were even needed at all.

But first, we start with a predecessor of Crossrail.

Liverpool Street railway station

For a very short period of time, it was possible to catch a Metropolitan line train from the mainline platforms at Liverpool Street station and travel to Paddington via the Underground.

Built in 1874/5, a tunnel creates a link from the underground railway to platforms 1 and 2 on the mainline — to create a temporary terminus for the Metropolitan line while their underground platforms were still being constructed. Intended to allow the Met line to run out to Walthamstow, it ceased use just six months later, and fully closed in 1904.

The tunnel’s name is interesting. It used to be simply the Great Eastern Railway (GER) Connection Tunnel, until a Queen used it, as it is said that the Queen Victoria Tunnel was used for special after-hours services carrying the Royal Train from near Buckingham Palace to interchange with services to Sandringham.

The tunnel still exists and was used for a staff canteen and storage, and for a while by the City of London police. The remainder of the tunnel will eventually accommodate a passageway from the existing London Underground station to the Elizabeth line station.

But to build a proper mainline railway crossing central London, we first turn to the canals.

The Regent’s Canal Railway Company

The Regent’s Canal built in 1812-1820 was, perhaps surprisingly, not a huge success, and within a couple of decades, it was being looked at as a possible route for a cross London railway, linking London’s docks to Paddington, via the City.

In 1845 plans were approved to sell the canal to investors who set up the Regent’s Canal Railway Company to convert the canal into a railway. That failed to raise the money, so died off.

Later schemes tried to build a railway next to the canal, but that required buying up more land and were doomed to go nowhere. An 1860 scheme came closest, but the arrival of the world’s first underground railway in 1863 pretty much killed off this first attempt at a cross London rail link.

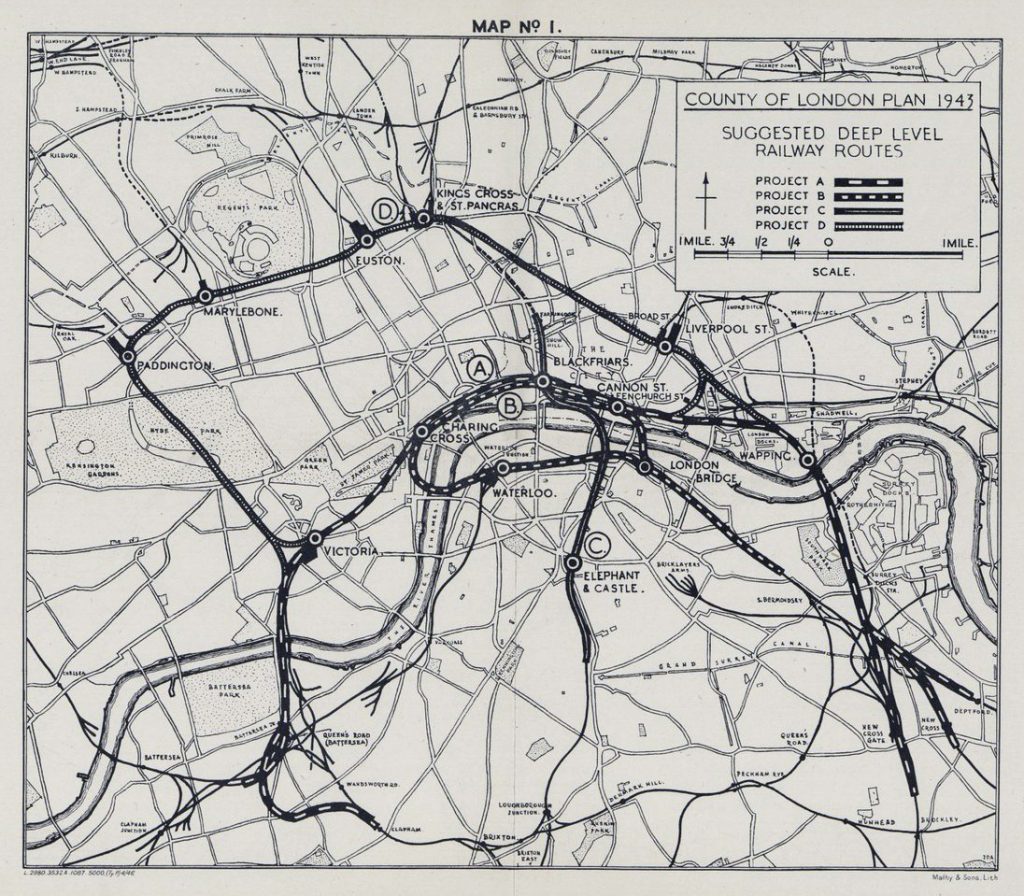

The Abercrombie Plan

Serious plans for an east-west railway formally came into publication in 1943/44 when what are known as the Abercrombie plans for London rebuilding after WW2 were released.

The report concedes that before the war, the mainline railway companies had already been working on plans for a mainline gauge railway to run under London, although the war and later nationalisation killed them off.

So the report is more confirming what others had already been planning, so the plan put forward is far less than its reputation would suggest.

What was proposed was just a series of loops aimed more at offering an opportunity to rebuild the mainline stations, and in the case of Charing Cross, hopefully bury it underground.

Although it was the first serious report to publicly call for a cross-London railway and its fame considerable, its practical impact is just a footnote in Crossrail’s long path to being built.

The 1968 London Transportation Study

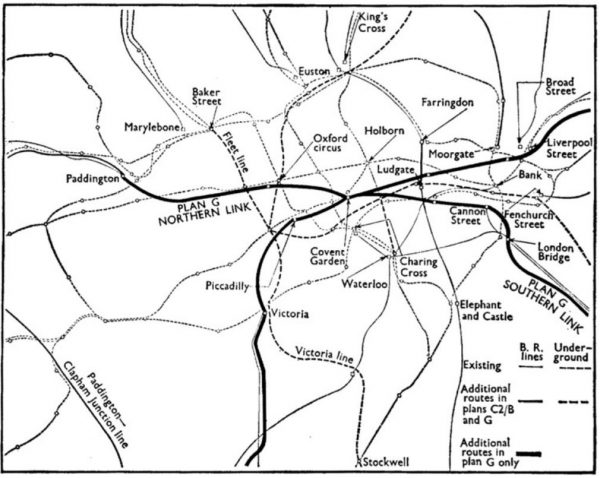

This was a rather interesting plan, in that it would have created quite literally a cross under London.

The proposal was for two lines, one running from Victoria to London Bridge, via Covent Garden, and a second running from Paddington to Liverpool Street, also via Covent Garden.

Covent Garden would have been a major underground railway hub. If this sounds fanciful, it’s worth remembering that at the time, Covent Garden was being closed as a market, and had been earmarked to be demolished for a new development.

However, this was also still the era of the motorcar, and the report itself noted that returns on investment were projected to be higher for new roads than new railways.

The 1974 London Rail Study Report

This is often seen as the father of Crossrail, as it was the first time that the term Crossrail was used to describe a mainline railway running under central London.

It however was largely a reprint of the previous 1968 plans, with two Crossrail lines, meeting at a hub near Covent Garden. The timing was however poor, as the report would have been written while Covent Garden was still likely to be flattened, but just as it came out, the market buildings were listed and preserved to become the tourist hub they are today.

While that was in itself hardly enough to stop a major railway project, it did hurt badly, and when the numbers were looked at, the railway was still not seen as economically viable. This was mainly a constraint of how such judgments were made at the time which were far less sophisticated than today, and also the railway was looked at in isolation, and its wider impacts were not included.

The financial crisis in 1973-5 and a still declining population in London put the £300 million plan on hold.

Its main legacy though is for our future – as it strongly recommended the Chelsea-Hackney route, which is now likely to become Crossrail 2 in a few years time.

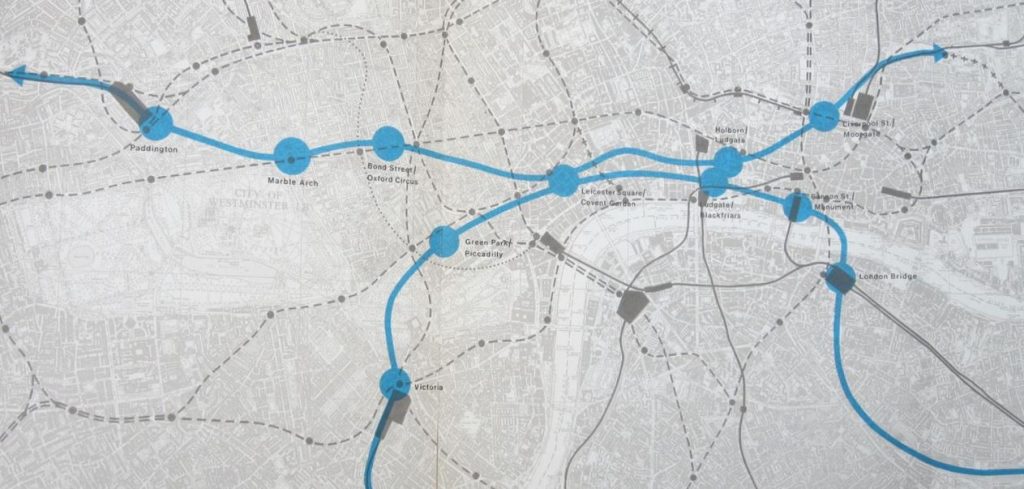

The 1980 British Rail Proposal

Published in November 1980 was a plan by British Rail for a Cross-London Rail Link. The name Crossrail does not appear in the document.

Published in November 1980 was a plan by British Rail for a Cross-London Rail Link. The name Crossrail does not appear in the document.

It’s also notable that the plan was more interested in improving north-south travel than east-west, which British Rail felt was already adequately catered for.

What was being suggested was less of a dedicated line than a joining up of several mainline termini. For example, there’s be a link between Paddington to Victoria, and another from Victoria to Euston, and another weaving around linking Waterloo, Farringdon and Kings Cross.

It was costed at £330 million in 1979 prices.

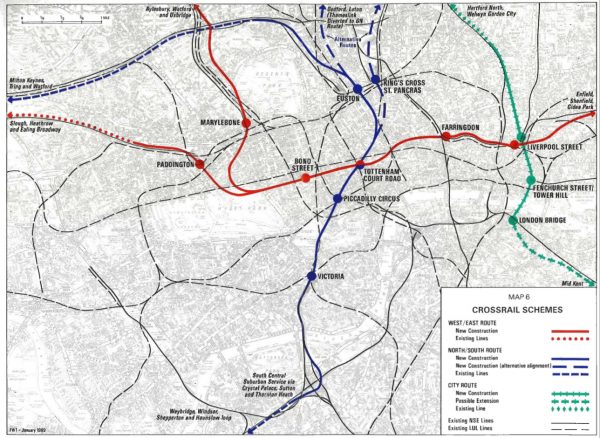

The 1989 Central London Rail Study

This was a wide-ranging report into public transport in general and proposed £3.5 billion of upgrades for the railways, but there were doubts about who would be picking up the bill.

This was not just a Crossrail though, but THREE Crossrails.

The front-runner in the plans was the Crossrail we have today, running east-west across central London.

But there were to be two more lines built, a mainline gauge Crossrail service between King’s Cross and Victoria costing £840 million, plus a new £1 billion tube sized line along the long-planned but never built Chelsea-Hackney route. If approved, it had been expected to open in 1996.

Today what is Crossrail 2 is a merger of both those schemes, and is unlikely to open before the mid-2030s, and cost around £31 billion.

Padderloopool line

Yes, it was actually called that in the report — a line running from Paddington to Waterloo to Liverpool Street. It was however far outside the funding options available so remained just a funny name.

The rest of the plans were warmly received, and while some modest upgrades were carried out, the main thrust, for a large scale capacity increase on the train lines were not.

It wasn’t a dead document though, as later that same year when the Jubilee line was given the go-ahead, Crossrail was simply delayed by a year, not cancelled.

Government Approval

In October 1990, at the Conservative Party Conference, the Transport Secretary, Cecil Parkinson announced plans for a £1.4 billion Crossrail line. This was to be a joint scheme between British Rail and London Underground with work starting in 1993.

Crossrail would have been due to open in 1999.

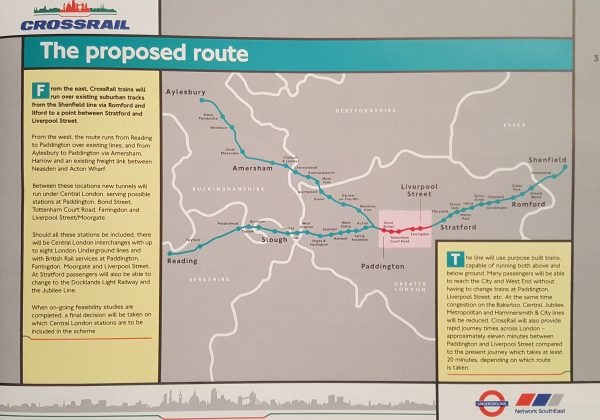

In July 1991, the new joint venture showed off their plans, known then as CrossRail, which now were costing £1.5 billion, and later that year, the Crossrail bill was presented to Parliament.

The plans didn’t include the current Canary Wharf/Abbey Wood line, but did include a line on the west side from Paddington to Aylesbury, via Wembley Stadium.

By 1993, costs had reached £2 billion, and with concerns about cost overruns on the Jubilee line, Crossrail was ordered to seek cost savings to prevent the bill from being killed off by government cost cuts.

In May, the Prime Minister, John Major signalled his support for the railway in a speech, saying that while costs were still a concern, the railway would be getting Parliamentary approval the following month. In the UK’s parliamentary system, just because a Prime Minister says something, it doesn’t always mean the MPs will agree, as was to be the case once more.

American Spies

Before that though, a very curious development, as the US government attempted to block Crossrail.

The reasons are to this day still unclear, but the proposed route went close to a building not far from the US Embassy which was suspected to hold sensitive communications equipment — and if so, that would have been affected by the tunnelling and later the trains.

The US government did accept that the US Navy “might” own a building near the route, but refused to elaborate on why the US Embassy was seeking to block the construction of the railway. With fighting between the Department of Transport and the Treasury rumbling on over the next few months, the American spies probably didn’t need to intervene anyway.

The Prime Minister again made a personal intervention in January 1994 to support the railway, which was still lumbering slowing through Parliamentary approvals, but it looked likely to be a success at last.

Killed by just three MPs

Then the dreaded day — 11th May 1994 — the plan was killed off, by just three MPs.

A House of Commons committee made up of four MPs had been overseeing the private bill, and those four MPs held absolute power over whether the railway would be built. Three of them ruled that the project would not be approved.

Tony Marlow (Con), Ken Purchase (Lab) and Dr John Marek (Lab) all voted to veto the private bill. Matthe Banks (Con) voted to support it.

Steven Norris, the London transport minister was said to be so furious as to be barely on talking terms with Tony Marlow after the vote.

The idea that just four MPs could derail such a massive scheme was already known to be a risk and their powers were already being constrained. Sadly, the Crossrail bill was one of the last to go through the old approvals process and hit the buffers.

Desperate attempts followed in the following weeks to get the bill back into Parliament, including digging out a 158-year old procedure to force the Committee to explain its decision. However, even a petition by 280 MPs was unable to force the committee to look again at the issue, nor even to explain why they took the decision to block the bill.

A couple of months later, the government moved to push the bill forward through a new procedure to get around the stubborn Committee. The cost had now risen to £2.6 billion.

However, the scheme was shelved the following year, and any attempt to revive it would lay with Railtrack, which was rather busy with being privatised at the time.

A few years later, in 1999, the City of London tried to resurrect the Crossrail line, but politics had moved on, and John Prescott MP, who was in charge of transport, said that it was for the new Mayor of London to make the decision. The first Mayor wasn’t due to be elected until the following year, so the government effectively kicked Crossrail back into the long grass.

The 2001 London East-West Study

In February 2001, Sir Alistair Morton, chairman of the Strategic Rail Authority presented a report to John Prescott calling for work to start immediately on the new cross London railway to “prevent the collapse of the tube network”.

The east-west route, now costing £3 billion was needed as the tube network was now so overcrowded that even a small problem could have massive implications for commuters.

This was to be a different Crossrail from the previous plans though.

It would run through central London as normal, but there wouldn’t have been the spur running through Canary Wharf and out to Abbey Wood, nor did it include the link to Heathrow. So just a single line without any junctions. This was hoped to open in 2011/13

The report also however called for Crossrail 2 — the Chelsea-Hackney — line to be built at the same time, opening a few years later in 2015/17, and costing £5.3 billion.

Although that report didn’t get far, it did spur the government into action, committing £150 million to draw up plans for a new Crossrail route. That’s on top of the £100 million spend in the 1990s planning the line. That previous spend wasn’t a total waste, as planning approvals in the subsequent decade had made sure that nothing built in the 1990s could block the proposed Crossrail route.

Construction was expected to start in 2005, and the line open in 2010.

However, this plan still lacked the Docklands spur, and there were concerns that Canary Wharf’s attempt to ensure Crossrail came to its offices would delay the project, and push the costs skywards.

The Mayor of London was backing Canary Wharf at a time when the Jubilee line was already starting to show the strains of the commuter traffic.

The larger proposal, costing £11 billion was finally presented to the government in October 2002.

A rival private scheme was also sent to the government, which claimed to be able to deliver a similar railway quicker and cheaper than Crossrail.

The scheme faced more delays as the cost raced upwards to somewhere between £10 and £15 billion, and the Treasury was sceptical about transport cost projections following massive overspends on both the Jubilee line extension and Channel Tunnel rail link.

Hopes to have Crossrail open in time for the 2012 Olympics were now dead.

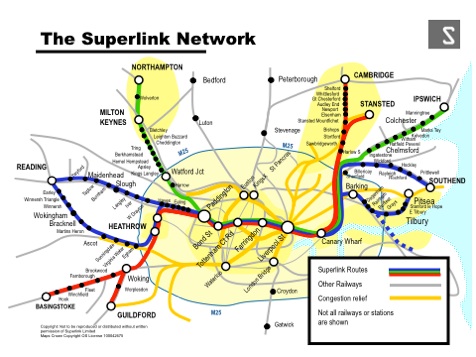

The 2004 Superlink

This was a counter-proposal that would have seen Crossrail extended considerably outside London, reaching out as far as Cambridge, Ipswich, Milton Keynes and Guildford.

The plan came from two railway managers, John Prideaux and Michael Schabas, who felt that the smaller Crossrail offered poor value for money and failed to address wider commuter issues in the South-East of England.

Although the Superlink was around a quarter more expensive than Crossrail, and would have cost around £13 billion in 2004 prices, the report argued that the wider benefits made Crossrail more affordable.

They also said that as the line would reach a wider catchment area, its overall running costs would be lower thanks to higher fare revenues.

Cross London Rail Links (CLRL), a 50/50 joint-venture between TfL and the Department for Transport (DfT) looked at the plans and rejected them outright.

Their main concerns were that the single Crossrail tunnel through central London would never be able to cope with so many divergent lines coming in from so many different directions. They also suggested that the project was optimistic in its costings, which they put at more than 55% higher than Crossrail.

The proposal also angered a lot of other railway people who had been working hard on pushing Crossrail and were worried that a counter-proposal would give politicians an excuse to delay approving Crossrail.

That said, the eventual Crossrail line did adopt a few of Superlink’s more detailed aspects, and there is still a lingering aspiration to expand Crossrail to reach further out of London in the future.

Crossrail gets approval at last

In May 2005, the government announced that it would support the Crossrail project, and would put a bill before Parliament. It also cut the line back a bit, terminating at Maidenhead and Abbey Wood, not Reading and Ebsfleet as originally expected.

By the end of the year though, over 350 objections had been sent to the Select Committee overseeing the bill, which worried people supporting the railway project.

A vocal critic of the railway, George Galloway, MP for Tower Hamlets where the line would pass through was criticized for missing debates on the railway — as he was pretending to be a cat in Big Brother. The interim report into the railway was published in May 2006, which with some amendments looked favourably on the plan.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t enough to get approval, and the matter rumbled on, with concerns about the rising costs — now put at £16 billion — and a decision about how much the government would contribute pushed back to Autumn 2007.

Approved!

The Times, 6th Oct 2007

On Friday 5th October 2007, the Crossrail project was approved by the Select Committee, and then moved to the House of Lords.

It was granted Royal Assent on 22nd April 2008.

The cost of the £16 billion railway is being split three-ways, between passenger fares, business and taxpayers. Transport Minister, Lord Adonis later admitted that he expected the railway to cost closer to £20 billion when complete.

In the end, cost-cutting, in part an unexpected consequence of the recession crashing the cost of commodities, saw the price cut to just under £15 billion.

That is made up of £1.9 billion from TfL, £5.2 billion from developers, £4.8 billion from the government, £580 million from the City of London and Heathrow Airport, and £2.3 billion spent by Network Rail on its own upgrades.

Construction Starts

Although the first major construction work was several years away, the first significant move was when Crossrail sent compulsory purchase orders to property owners in the Tottenham Court Road area, including the Astoria nightclub.

Demolition works there, and on other sites started in Spring 2009.

The formal construction start though, in a flurry of publicity, took place on 15th May 2009 as a foundation stone was laid at Canary Wharf.

The construction of London’s new railway was finally underway.

Sources

- County of London Plan 1943

- From Brunel to British Rail: The Railway Heritage of the Crossrail Route

- Central London Rail Study

- The Times, Wednesday, December 15, 2004

- The Times, Friday, January 27, 1989

- The Times, Friday, November 17, 1989

- The Times, Wednesday, July 03, 1991

- The Times, Thursday, June 03, 1993

- The Times, Wednesday, May 11, 1994

- The Times, Wednesday, June 29, 1994

- The Times, Friday, February 09, 2001

- The Times, Friday, May 04, 2001

- The Times, Thursday, May 01, 2003

- The Times, Monday, May 07, 2007

- Work on London’s £16bn Crossrail scheme begins

- What If: Crossrail 1980

- Revisiting the growth coalition concept to analyse the success of the Crossrail London megaproject

- Crossrail: the slow route to London’s regional express railway

- Former Broad Street Ticket Hall and Queen Victoria Tunnel Built Heritage Recording Report XSM10

Fantastic and interesting article to read. Thank you.

The Elizabeth Line in the future (2020-onwards) might extend from Old Oak Common to Tring & Hemel Hempstead, Watford Junction and possibly as far as High Wycombe and Aylesbury.

Or the Elizabeth Line may extend to Didcot Parkway, Newbury & Oxford from Reading.

Extended from Abbey Wood to Dartford, Gravesend, Rochester Strood, Gillingham and Faversham.

Extended from Shenfield to Southend Victoria, Wickford, Southend Airport, Southminster, Chelmsford & Beaulieu Park.

Extended from Stratford to Southend Central, Grays, Tilbury Town, Shoeburyness, Pitsea, Basildon, Leigh-on-Sea, Ockendon and Chafford Hundred via Barking/Upminster/Rainham.

Extended from Slough to Windsor & Eton Central.

And finally extended to Staines from Heathrow Terminal 4 & Terminal 5.

The Elizabeth Line may extend to other towns & cities outside of London.

I know, why not extend it all the way to Dover or Norwich? or how about Penzance or Cardiff? that would be really spiffing.

Crossrail is supposed to provide a new service in London, for London, not take over all the lines around London. Extensions to Tring and maybe Dartford have been discussed, but your, very long, lists are just stupid fantasies. So put your crayons away and stop writing out long lists of stations.

Now, now, no need to be rude, is there?

Besides, services in London, for London, really do include all the commuter routes into London. Crossrail 2 is designed to alleviate pressure on the commuter routes coming in from South West London and Surrey, for example. Extending the Elizabeth Line out to other commuter towns isn’t a stupid fantasy.

Also there used to be a Norwich-Basingstoke service operated by Anglia Railways known as London Crosslink which only lasted for few years and went via the North London Line.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Crosslink

Wouldn’t mind if you can get a train from Southend Victoria and Wickford to Basingstoke without having to change at Stratford or Liverpool Street and to use the Underground to get to Waterloo and use SWR train to Basingstoke from Waterloo. As the route would take you via the North London Line and freight line that would connect onto the Basingstoke line. Even though it would be longer but it will be hassle free journey.

The more I look at Crossrail’s design, the more I’m convinced that we ain’t seen nothing yet!

Consider.

1. Although the line is being built with a capacity of 24 x 9 car trains per hour, various documents talk about 30 x 10 car trains per hour. That is a 39% capacity increase.

2. Extensions to Ebbsfleet, Gravesend, Beaulieu and Southend are possible without major infrastructure, except signalling to increase frequencies on the ~North Kent Line and the Great Eastern Main Line.

3. Some of the possible connections to the Underground and lines like the Northern City Line look to have good possibilities.

4. The line seems to have been designed well with respect to extendability and connectivity.

I think a lot depends on how Londoners and visitors like the line. If it is successful, I suspect various boroughs will clamnour to create links to their areas.

The most important feature is to keep the Crosstalk network as simple as possible. Doubts have already been expressed about the complexity of Thameslink and having more and more arms feeding into the core route of Crosstalk will only lead to unreliability.

The wilder imaginations of some correspondents should be ignored. Having cross-platform interchange with parallel routes is a much better solution eg. Stratford “good”, Abbey Wood “bad”.

Good article. However maybe an exaggeration to say that “the Elizabeth line (nee Crossrail) will increase central London’s underground rail capacity by around 10 percent. To put that into context, it’s equivalent to lengthening every tube train passing through central London by an additional carriage”.

Tube trains have 4-8 carriages and so an additional carriage on each would increase capacity by a fair bit more than 10%?

Regards

Wow Andrew, what a great idea! You could call it SuperLink.

Thanks.

I feel that one day in the future London will collapse into one almighty big hole!!

Having main line gauge lines meeting at the old central market is what Paris did with the RER at Chatelet (apologies for lack of circumflex). Maybe the British planners were looking at Paris even in the 1960s.

The only extension being looked at is up to Tring and that is only at feasibility study level and because it can use the Paddington terminators (although more stock will be needed).

Adding more destinations means the trains are busier and makes regulation/timekeeping more difficult through the core section more difficult. This is a TfL train and it is not in their interests to make the trains too busy or cause delays through their key market. TfL didn’t want to extend the line to Reading for these reasons, but were over-ruled. So my prediction is that there will be no extensions for many years because TfL don’t want them.

Just because it is technically simple to extend the services doesn’t mean it makes sense from service point of view.

A most interesting article, thanks.

Since there have been a number of proposals to reopen the Bishop’s Stortford – Braintree branch line, what is the likelihood of Crossrail eventually taking over the route in order to potentially allow it to reach Stansted airport from Shenfield?

One older Crossrail or Thameslink like scheme not mentioned would be the London Central Railway proposal during the 1870s, which entailed a Snow Hill style tunnel linking Euston to Charing Cross roughly following a similar route to the later Charing Cross branch of the Northern Line (either butterflying away or radially changing the latter).

Regrettable nothing become of the other (IMHO) viable Crossrail proposals so as to connect virtually all the various terminus in London.

I may be getting something fundamentally wrong here but isn’t the idea of Crossrail that it’s a stops-everywhere service that just happens to be faster, more frequent and bigger than the tube? Great for crossing London, getting from Heathrow, going to Canary Wharf and so on. If Crossrail followed the same principles and had a service that started in Brighton it would take an age to reach London. Already, with the Reading service it would probably be faster to take an InterCity to Paddington to change than to take Crossrail which would make lots of intermediate stops so the rational of a fast service is already lost.

Most passengers going from Reading to London will no doubt use faster GWR services especially as Elizabeth Line will only be two train a hour. However, Reading is a destination in its own right and so may encourage reverse commuters or those heading to Reading to change to long distance trains .

Seems this article will need updating to new opening dates !

Let’s not make all the same mistakes in the North. Get cracking with CrossRail North from Merseyside to West Yorkshire via Greater Manchester when the boring machines have be recovered from CrossRail!