Over the years there have been many attempts to build a bridge across the Thames near St Paul’s Cathedral, and this is the story of one of them.

In 1906, the noted architect, Mr T Collcutt proposed a new bridge to run from the eastern side (the back) of St Paul’s Cathedral across the Thames, and that it should be in the model of old London Bridge, with shops along it.

This was no mere architects fancy, but a practical solution to a problem — just how do you pay for a bridge? Not just building it, but also maintenance. Bridges cost money, but don’t generate revenues, except that London Bridge had, thanks to rents from the shops along it.

Jump forward a few years, and in 1909, there was stronger pressure to build more bridges across the Thames to relieve increasing road congestion, and Mr Collcutt popped up again.

Plans were already underway for a bridge in the area, some 80 feet wide, and he proposed making it 116 feet wide, with a row of single-story buildings and a colonnade above the pavement to offer shelter to pedestrians.

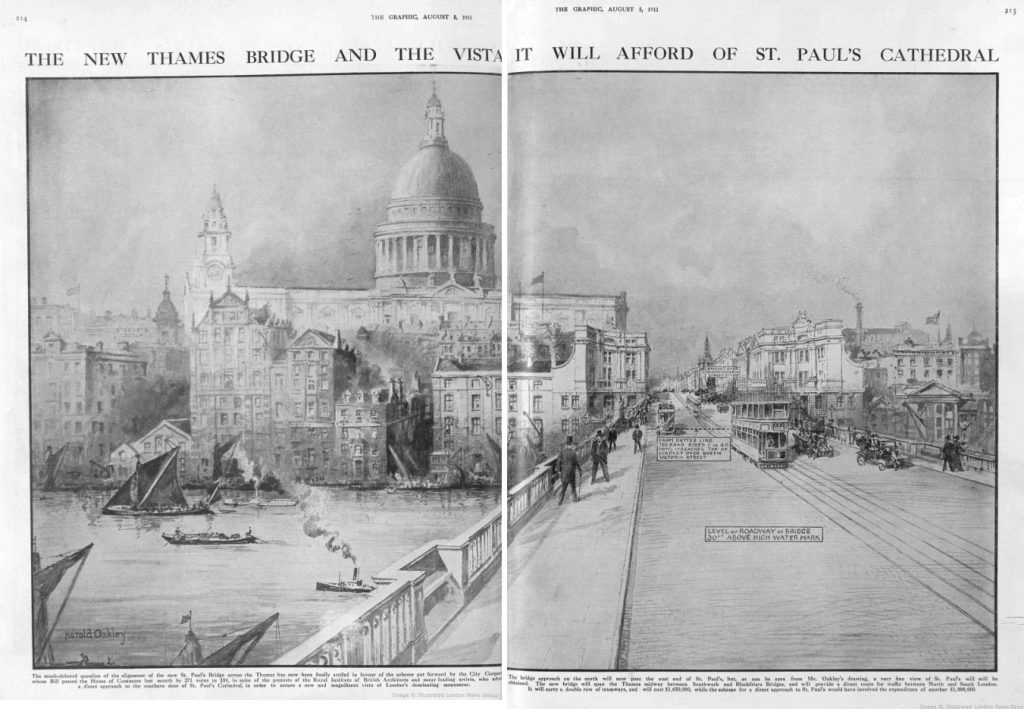

The debate of shops or not aside, there was also the debate about its location. Most favoured a straight line running behind the back of the Cathedral, so but some wanted a bridge to run roughly where the Millennium footbridge exists today.

The argument being that it would offer a more pleasing view to motorists, while ignoring the fact that it would have turned the Cathedral into a giant roundabout.

Mr Collcutt’s concerns seem odd though, as bridges constructed within the remit of the City of London are funded and managed by an ancient trust, the Bridge House Estate, which uses the surplus from its investments to maintain bridges across the Thames. It’s still at work today.

However, although the City’s Bridge House Estate recommended the bridge be built, the Aldermen decided against it, and in July 1909, narrowly voted against the proposal, but kept it open for further consideration.

And a few months later the London County Council was offering to stump up £350,000 towards the cost of widening roads near to the planned bridge, to accommodate trams. By now, the City was sufficiently confident of the plans, that it sought a bill in Parliament to approve the construction of a £1.36 million bridge, and the approach roads.

As with modern times, bridges across the Thames can be surprisingly contentious, and this was no different, with an army of voices raised up in protest against the plans, which they feared would despoil the view of the Cathedral.

One of the louder voices in support of the bridge though was The Sphere, who took up part of the earlier idea for shops, with a colonnade, and campaigned for bridges to come with covered walkways for pedestrians. But not the shops.

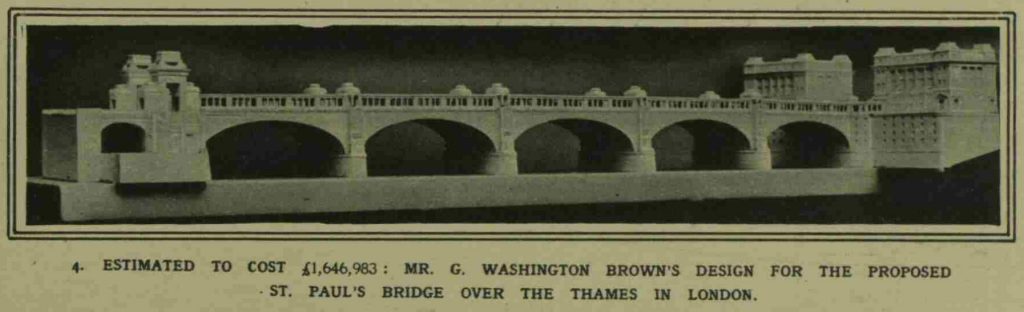

The biggest critics the bridge was facing was that it had been designed and planned by engineers, and not architects. Always a prickly lot, the architects were extremely annoyed that they had not been consulted and that the bridge was in dire need of their attention so that if built, it would at least look nice.

The City was able to secure Parliamentary approval though, and the London Bridges Act 1911 was duly passed.

Although the City remained keen on the bridge, it almost killed it of themselves, by approving works to reduce the steep hump in the middle of nearby Southwark bridge, which made it a pain to get over. In doing so, they speeded up road traffic to the point where a bridge at St Paul’s looked less necessary than originally thought.

However, human and road populations continued to grow, and by the 1920s, the plans were back on the table once more.

By December 1920, the Lord Mayor, Alderman Roll was confidently predicting that work on a St Paul’s Bridge would start shortly, although the cost seems to have risen to “many millions”.

By late 1922, the City reported that it had bought up the lands necessary for the approach roads to the bridge, so that construction could start at last. However, the government asked for a delay, pending a report on road traffic that it had commissioned.

Although the roads report was favourable, a different Royal Commission issued its own report on river crossings, and proposed four new bridges, and the scrapping of the St Paul’s bridge.

In 1929, the government refused permission to extend the bill’s provision for another 2 years to give the City of London time to build the bridge, but by then, even the City was having second thoughts about the suitability of the project. A year earlier, its own Court of Common Council had rejected extending the project deadline, although they had to go through the formalities in Parliament.

Later surveys had found the contradictory view that the bridge would both be underused, so a waste of money, and also to attract so much traffic that vibrations would undermine the Cathedral’s foundations.

A survey of road traffic plans by Lord Lee’s Commission was also noted for omitting the bridge from its suggestions.

By now the country was on the verge of the Great Depression, and further expenditure was not thought possible.

The City Corporation had already spent a considerable amount buying up freeholds along the route of the bridge, but most of this was land that could easily be resold again later.

Eventually, we ended up with a wobbly bridge, for pedestrians, and not in the originally planned location.

A curious legacy though of those earlier plans is that the City didn’t sell all the land it had bought, and still to this day owns a number of plots of land in Southwark where it has council housing. And that is why you can find the City of London sign on buildings south of the river, a legacy of plans to build a river bridge that never happened.

Sources:

The Sphere, 4 Dec 1909

The Shoreditch Observer, 18th Dec 1909

London Daily News, 15 April 1910

London Daily News, 3 Nov 1910

London Daily News, 14 March 1911

The Scotsman, 15 Feb 1929