Exactly 200 years ago, the architect of the Crystal Palace proposed a grand scheme that would have seen the centre of London roofed over with a huge glass dome.

The years running up to 1816 had been noted for their unusually high rainfall, and at a time when many roads were still unpaved, and even in the city, drainage was poor, this had caused considerable problems.

The number of horses being put-down after breaking legs during falls had reached an all time high, and demands were equally high for something to be done to improve the situation.

Thus, on April 1st 1816, a Royal Commission on the Improvements of the Wayfares of the Metropolis was set up with a remit to investigate what could be done to improve the roads.

While a number of suggestions were made to improve drainage, or hire large numbers of children to clean the streets, it was an audacious plan by recently ennobled Sir Joseph Paxton which was to fire the public imagination.

Fresh from the success of the Great Exhibition, having proven the principle of mass production of huge sheets of glass and prefabricated ironwork — a mighty scheme was conjured up.

Rather than trying to make the roads suitable for use during the bad weather — why not divert the weather itself?

A series of massive towers would be constructed, and then iron spans constructed between them, and eventually, infilled with glass panels. A huge dome covering London to protect it from the incessant rainfall.

The scheme would only have covered the main part of the City of London, as that was the limit of the Royal Commission’s review, but also as to extend it further would have been proportionately vastly more expensive. But the proposal did leave open the option to expand later if funding could be secured.

To keep costs down, and the structure up, Paxton’s scheme called for the centre of the glass roof to be supported, not by tall pylons, but by tall buildings which would also then cover the costs of the construction of the dome in the centre of the City.

It was anticipated that 20 such tall office blocks would have been needed around the City — which apart from the dome itself, would have radically transformed the appearance of London’s skyline.

Imagine a 1960s vision of tall towers laid out in regular grids, and this is what London was planning in 1816 — just made from brick and iron instead of concrete.

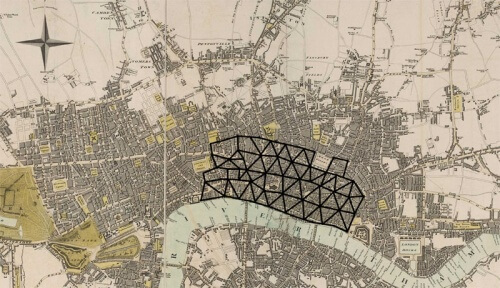

A contemporary map showing of the layout of the office blocks and edge towers.

Due to its height, one old dome would have punctured the modern glass dome — that of St Paul’s Cathedral. It was also expected that the public walkway around the outside of St Paul’s dome would offer views across the top of the glass surrounding it.

In fact, a number of viewing platforms and access to the top of the glass dome were proposed for the office blocks, and some discussion about whether the iron work could be made strong enough to act as skyline footbridges linking the new offices.

It was however felt that such additions would so encumber the ironwork that there would be less glass than iron to the point that the streets below would be in permanent shadow.

Further to the edges, tall standalone ironwork towers were planned, and a competition was held to design them.

It was a good 80 years before Paris was to get its iconic tower, but London was on the verge of having a dozen of its own — albeit nowhere near as tall. It was expected that at its highest, the dome would have been no more than 8 stories above the street.

It was however these pylons which were to prove the downfall of Paxton’s mighty imagination.

In order to test the construction potential for the iron towers, a sample was constructed on the edge of the City, in Temple Gardens next to the Thames.

Construction started a year after the Royal Commission was set up, on 1st April 1817.

While the base of the tower was itself viable, the construction alarmed the city authorities due to the unexpected size of the tower, which they had been led to understand would have a much smaller footprint.

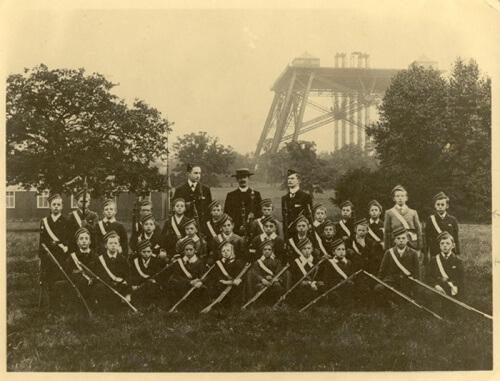

The unfinished stump as seen from Blackfriars bridge, circa 1872.

The disruption of the construction works also caused concern with voices being raised now to ask if simpler schemes might be less of an incumbrance to the city.

A petition was raised and presented to Parliament just a few months after the initial construction started, calling for a halt to “this monstrous folly on the Thames”.

And Parliament listened. The project was halted pending a review, which later decided that the dome was just too outrageous a scheme, and put an end to the limited funding that had already been agreed.

And Parliament listened. The project was halted pending a review, which later decided that the dome was just too outrageous a scheme, and put an end to the limited funding that had already been agreed.

However, as is often the case with political decisions taken in haste, while funding was swiftly withdrawn, the politicians forgot to leave enough money to cover the cost of removing what had already been built.

Therefore, for several decades, the grounds of Temple in the City were noted for the iron platform that loomed over the learned buildings of the legal profession.

It was not until the construction of the new Embankment by Joseph Bazalgette for London’s new sewer network that the remains of the tower were torn down, as they now intruded on the construction site.

It’s claimed that the iron work was reused for the construction of the later Metropolitan railway, which was at the time chaired by Sir Edward William Watkin.

Never built, it wasn’t long afterwards that an idea for personal domes of protection gained prominence, as Jonas Hanway popularised the common umbrella. Now people would carry their own domes around with them.

However, what if the glass dome had been been built?

Sadly, it’s highly unlikely that much of it would survive today. The dome would almost certainly have been torn down during WW1, when aerial bombing of cities became possible.

The office blocks having lost their secondary functions would have been redeveloped, and the iron towers likewise, torn down and the land used afresh.

Maybe one or two towers would remain, as relics of this most curious of plans.

The stump became a bit of a tourist attraction for a few years – here in Temple Gardens.

April Fool!

Yes, it’s that time of year again.

Sir Joseph Paxton would have been a mere 13 years old. Precocious he might have been, but that’s pushing it a bit.

The inspiration for the tower is the infamous Watkins Folly — an attempt to build London’s own Eifel Tower at Wembley, which never got above a single stage. The photo of the stump and the Thames, is actually of Paris.

Paxton did propose to build a massive glass roof over parts of London, but as a loop railway around the city – the Great Victorian Way

The surname of the MP in the letter might also sound familiar to long term readers sufferers of my April fools.

And all this time I thought the Great Exhibition was in 1851. The things you learn on the Internet!

There I was about to criticise the article for factual inaccuracy when I realised the date.

April fool to you too!

Like the second picture which is Watkin’s tower, isn’t it?

I think the first is Paris, though …

I would love to know more about the second picture; the boys look very young to be trusted with rifles, even by Victorian standards.

Found it; turns out to be Wembley Park Boys’ Brigade 1902-4. So Edwardian.