In the early 1970s, plans were announced to demolish a cluster of old buildings opposite Big Ben* and replace them with a vast monolith covered in bronzed glass.

The need for the building then was the same as for the current building which was eventually built, to offer more space for MPs in Parliament.

An architectural competition, organised by RIBA was held in 1972, and of the 246 entries submitted, one by Robin Spence and Robin Webster was the winning design, earning the two architects a handsome £8,000. The design would have cost £7 million to build (in 1972 prices) and was described as a squat construction clad in bronze and glass and a — radical for its time – computer designed roof lattice.

The building would have been suspended from the roof structure, and supported by four concealed service towers which would have straddled the District and Circle lines, while the main office floors were raised up above a covered square in the centre of the building.

Plans to open up the ground floor area to the public were swiftly dropped and a bomb-proof glass wall was added to the design. However, the top would have been a “secret room”, with a roof garden and views across London.

When shown off to the public, nearly 14,000 people visited an exhibition of the designs, although it was noted at the time, that fewer than half of the MPs visited the exhibition — which was after all about a new office for their convenience.

The GLC started expressing doubts about the design and various amendments were made to assuage their rising concerns. However, by the following May, even MPs were starting to get cold feet about the design. Later it was alleged that the government misrepresented the design to MPs in an effort to get more on side for a plan to quietly ditch it. Despite that, in June 1973, MPs approved plans to build the new bronzed slab next to the river.

However, although the architects carried on developing the scheme, construction never started, and an economic downturn made starting it even harder.

Eventually, in July 1975, the plans were dropped as costs soared from the original £7 million to £30 million (excluding the cost of the land), and MPs were told to look elsewhere for cheaper offices.

With its cladding of bronzed glass, it would have looked exceptionally dated within the decade. Today, with bronzed glass utterly decried as rightly awful, and the building unfit for modern use, it would have probably been demolished when the Jubilee Line came burrowing through the area.

And rather than a squat tired looking 1970s office block, we’d probably still have the current Portcullis House.

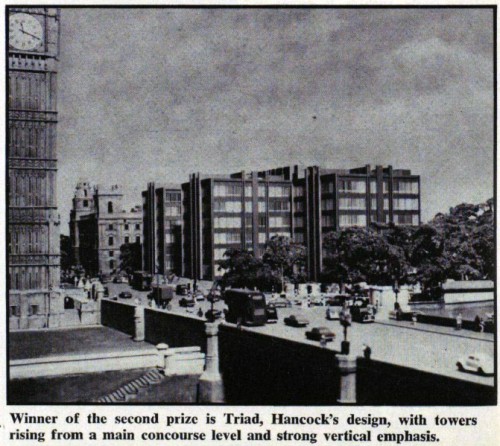

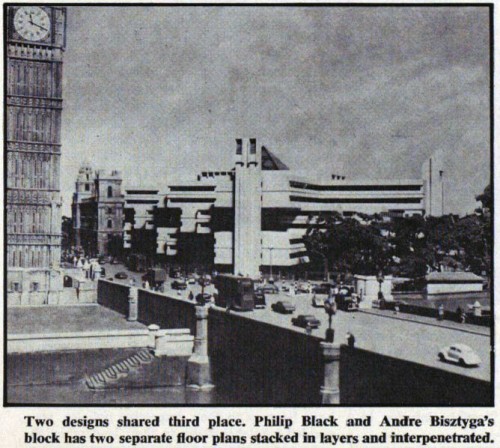

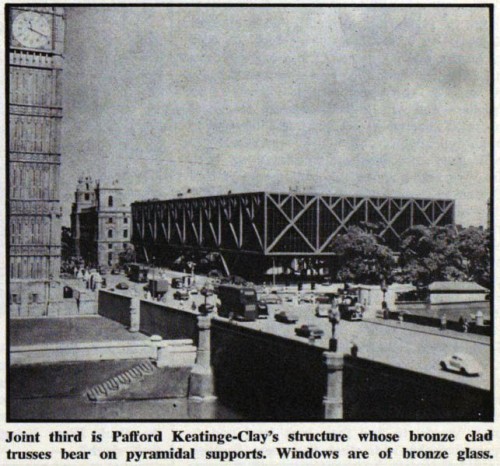

Or maybe one of the runners up:

Sources:

Illustrated London News, April 29, 1972 & November 25, 1972

Demolishing Whitehall, Leslie Martin, Harold Wilson and the Architecture of White Heat

Architects Journal, December 1972

The Times, 2nd March 1973, 17th July 1975

Building, April 1973

*yeah, yeah, whatever

“Interpenetrated”. F’narr.

I knew there was an abortive competition for a building on Bridge Street, but I had no idea it would have resulted in this… abortion. It would have looked so horribly out of place between its Victorian neighbours* that its unpopularity seems assured, with a probable fate much like that of the Palast der Republik in Berlin. On the other hand, Portcullis House may have shocked me a little at first, but I have warmed to it and this post certainly makes me like it even more. It is a building sensitive to its location, with an interesting profile and detailing that will stand the test of time far better than the strident sterility of ’70s modernism. The long delay in its construction looks like a blessing now, much as it must have grated MPs and the Commons authorities at the time (though it is really their long-suffering staff that I’m thinking about, working in rather bad conditions all those years in the Palace). And although the loss of the buildings that previously occupied the site—some of them listed—is regrettable (as indeed is the loss of the sense of scale that they provided to the much larger Palace compared with what stands now), I don’t think those could have been saved either way.

* From what I can see in the photographs above, Norman Shaw South (the Scotland Yard extension) would have been demolished, a recurring theme in plans from that time. There were many proposals for solving the accommodation crisis in the Palace, making this small area a particularly rich one for Unbuilt London. These proposals mostly concerned the erection of new buildings and often the destruction of others, such as the proposed continuation of the Palace of Westminster northwards, which would have entailed closing off Bridge Street. There was also the less unrealistic idea of enclosing New Palace Yard with offices, which was actually part of the original plans for the building; it ought to make for a popular and surprising post, as with any proposal to alter a very familiar landmark (or a very familiar view, which is partly what doomed the design).

In this context of ambitious but ultimately discarded plans, it is curious how the Parliamentary Estate seems to be taking shape: as a collection of pre-existing buildings mostly of the late 19th and early 20th century, and none of them custom-built for Parliament except Portcullis House (and the Palace itself). Things are still in flux, especially on the Lords end, yet one can plainly see that renovation is the order of the day. Unless I am mistaken, no new construction is expected to take place around the Palace for many years (minor additions like the visitors’ centre notwithstanding). Portcullis House was a necessary evil in a way, but otherwise the entire Estate is an example of preservation and adaptation at its finest.

The only way that proposed building would have worked is if they’d rebuilt the whole complex. Portcullis House, whatever else may be said about it is a much better ‘fit’ visually to the buildings around it.

In fact I have heard that the designers of a suppliment for the Call of Cthulhu roleplaying game had to replace an image of the Houses of Parliament they were using as a chapter header because they mistook Portcullis House for a 1920s building.