In the early 1890s, a Scottish architect published a grand scheme to rebuild central London. Away with tired old narrow streets and hello to Parisian boulevards. Goodbye to St James’ Park and hello to a massive road network and roundabout.

Arthur Cawston was rather better known for his ornate churches than for town planning, but in those days, town planning was more the whim of architects than the specialised science that it is today.

Hence, as the government was considering the creation of a London County Council, the architect saw an opportunity to turn London from a collection of towns and local municipalities into a single city with a single government — and importantly, a single architectural vision.

A vision that was heavily influenced by the great cities of Europe, where autocratic monarchies were able to sweep away the little people in favour of grand vistas. A similar sort of sweeping away was to happen in London, but for the requirements of the railways, not the whims of monarchs.

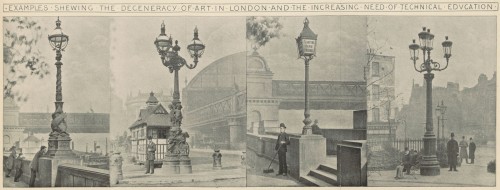

Writing in his proposal, A comprehensive scheme for street improvements in London accompanied by maps and sketches, Cawston bemoans the lack of coordination between local governments which lead to a mishmash of designs — and he seemed rather oddly fixated on the varying designs for gas lighting on the streets.

London has been allowed to grow into a shapeless and disjointed province of houses, with scarcely any cohesion or articulate voice to express its common wants.

He was also somewhat dismissive of the idea of paying compensation to those who might be dispossessed by his plans. While some of his complaints about excessive compensation were justified, he was very much of the view that a many individual losses were a price worth paying for the grand vision to come to pass.

In a more conciliatory vision, albeit with patrician overtones, he proposes the demolition of the Foundling Hospital, Chelsea Pensioners Hospital, Belhem Hospital, amongst other institutions, for the construction of “labourer’s dwellings”.

He estimated that 127,000 people could be housed on these plots of land — if built to a high density.

But it was the roads that were to take up most of his thinking.

London, like all other old cities, is a vast, tangled network of streets that for the most part begin nowhere and end nowhere.

He called for a London plan to be drafted which would set out long term goals for new roads and wider avenues to be constructed. The plan would have legal powers to buy up buildings where necessary for new junctions, or where short-term funds were not available, any existing building would be subject to restrictions on redevelopment in the future — to fit with the grand scheme.

Buildings which project over the new lines of frontage should never be allowed to be structurally renovated, and when at length it becomes necessary to pull them down, so much of their site as is beyond the new building line should be given up to the public

His plans called for the removal of 1,250 homes, which he expected to be possible within a 5-year timeframe, although he admitted that a similar idea for widening Ludgate Hill took fully 30 years to complete.

Can one imagine the enthusiasm and pride that would be roused some few years ahead as the last block of houses in each new thoroughfare gradually came down, and for the first time an uninterrupted view of the new street with its palatial architecture was obtained?

His attention, diverted from demolishing houses turned to the great parks. While, correctly lamenting how some small parks were mean sized affairs and not looked after, he seemed to have a dislike for the great St James’ Park.

A man who wanted wide open spaces and grand European vistas disliked the sort of park which seemed essential to the vision.

St. James’ Park, and indeed all our parks, have stood sadly in the way of street improvements for many years.

What he claimed is that as the parks lacked roads through the middle of them, people tended not to use them to their fullest ability. Seemingly, Victorian’s were scared of wandering off the pavement.

So to alleviate such fears, run roads through the middle of the parks. And put roundabouts in the middle of them to connect these roads. Instead of large open spaces, create clusters of small parks, dissected by busy noisy roads.

Wonderful idea!

But, wandering in the parks is not for the unwise — so the parks would be fenced off with railings, and the pavements made be wide enough for thousands of seats, so that Victorian’s could admire the parks. From a safe refined distance.

He did concede that the roads might disturb the peace of the parks, but as he noted, really the grass is only used for a few weeks per year, and mostly by undesirable sorts. So gentle ladies should not be too put out by the new improvements.

Despite his somewhat dismissive, if at the time fairly normal, attitude to the working classes, he was fully in tune with notions of how lofty ideals can improve the life of the poor, if less for their personal benefit than the elevation of the poor to the refined behaviour of the rich.

A large section of his treatise covered the requirements to improve the quality of air and light in London, although again his main solution was to widen roads. Today those roads would be filled with noxious fumes from motorcars — and even at the time of their proposed construction, they would have stank of horse urine and worse, and been intolerably noisy to live near.

But at least there would have been daylight.

The roads would also have been straight. Very straight. Better for road traffic, and apparently, policing, but lacking any of the curves of Regent Street or corners of the city that often peek out with interesting buildings.

London would have looked more like an American city with their grid layout of streets, and denuded of any redeeming character.

But, with wide roads and buildings modernised, finally London, the capital of a mighty empire would have the great grand roads and buildings that the author wanted.

Thank goodness he stuck to building churches.

Sources:

A Comprehensive Scheme for Street Improvements in London

London’s Teeming Streets, 1830-1914, James Winter

Most of his points are valid though, don’t you think?

“a vast, tangled network of streets that for the most part begin nowhere and end nowhere” – he could have written this today. The lack of thoroughfares is something that should’ve been fixed around his time.

Of course I love narrow streets and would rather live in such. But the fact that the M25 is often the quickest way between two points of London is telling something.