Do tube strikes cost the economy millions of pounds in lost productivity, or do they shake up people and change behaviour in a way that offsets the loss?

That’s indirectly, a question that has been asked by a group of researchers who took advantage of the tube strike to test a difficult to test idea, known as the Porter-hypothesis

Porter argued that – when information is imperfect – externally imposed forced experimentation can help people discover unexpected improvements in efficiency.

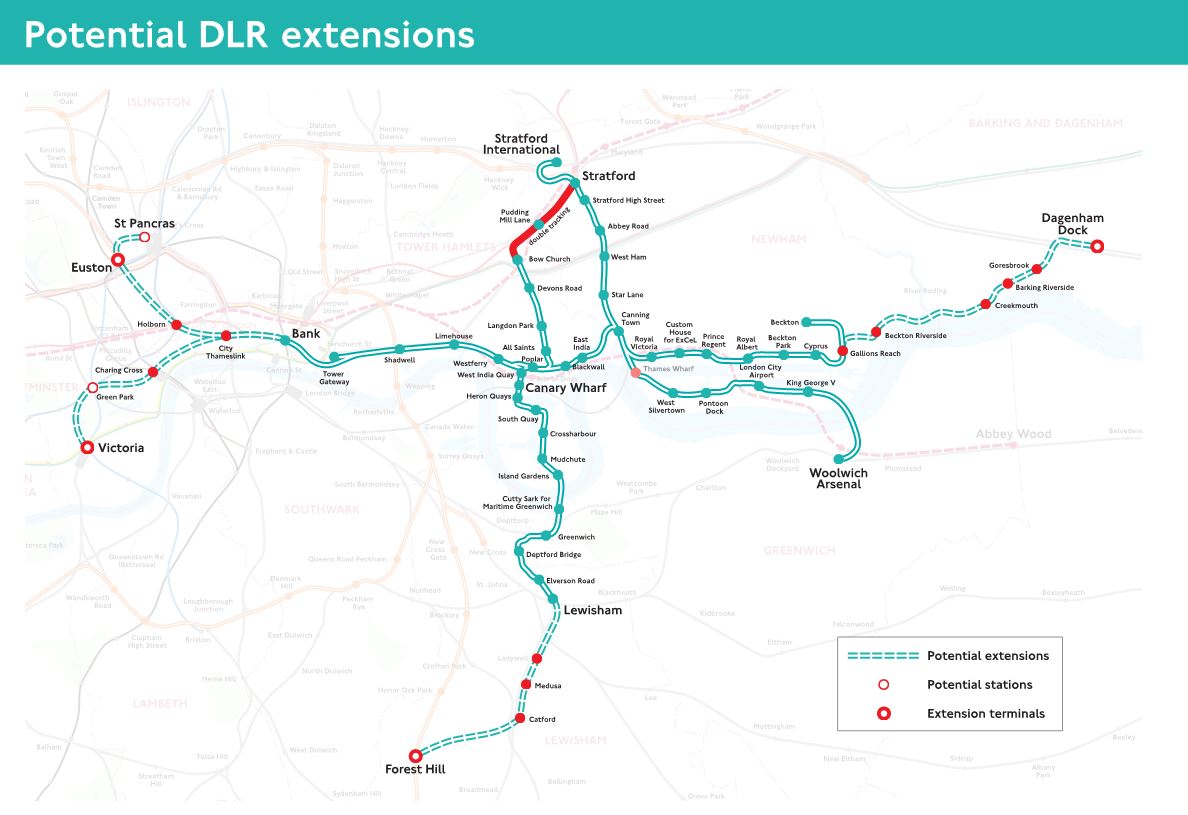

For example, the tube map famously shows some tube stations as being distant from each other, when in reality, they are physically close (Jubilee line/DLR at Canary Wharf), and people blindly follow the tube map, when local knowledge offers faster alternatives on foot.

One of the more interesting side effects of the Oyster card is that TfL knows how people travel around London, and uses that information in its long term planning — and makes some of it available to researchers.

Researchers, from the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford, examined 20 days’ worth of anonymised Oyster card data, containing more than 200 million data points, in order to see how individual tube journeys changed during the strike.

There is a theory that humans being imperfect beings do not always optimise how we behave. Then having got into a safe familiar routine, it’s very difficult to change.

Various tests of this, and attempts to see how shaking up our comfort zone have either been too artificial in nature, or too small in reality to offer meaningful insights.

Then there is a tube strike, affecting millions of people, and with computer data of how those people are affected — an almost perfect data set to experiment with.

The February tube strike in 2014 being ideal for research as less than half of tube stations closed, so commuters could still commute, but had to change their familiar behaviour for a couple of days.

And what did the researchers find?

Yes, people changed how they commute to work during tube strikes. Obviously.

But maybe nearly 5 percent of people then maintained their new route to work afterwards, having possibly found that their new route is preferable. The biggest effect was closer to central London, and this appears to be a factor of our reliance on the tube map for guidance.

As we should know, it is not geographically accurate, and the distortion effect is greatest as you get closer to the centre. So people who comfortably used one tube line may have found that an alternative station — geographically close, but seemingly distant on the tube map — was actually a better route to work.

This also took into factors such as different speeds on different lines, such as switching to a line with fewer stops, or faster trains.

The report only looked at morning commutes as these tend to be more static in behaviour — unlike commutes home which are often affected by post-work beers, shopping, sports, etc.

What was the net benefit then?

Based on a 4-year time-frame, chosen as half the average time spent using a single route to work, the time saved by those who changed their commute averaged to 40 seconds per day, or £380 over 4 years, based on the average London wage.

If then added up, across those who changed their commute pattern, you generate the headline friendly statement that the net cost of the tube strike is outweighed by the net economic gain from how people change their commute.

More tube strikes!

The caveat is the presumption that humans are too imperfect to find an optimum route to work, but so perfect that any time saved is used productively.

Small savings do indeed add up, for example, a series of 30 second efficiency gains in work processes can add up to minutes per day — time for one more email/phone call. However, I doubt that a small stand-alone saving, such as on the commute can be counted as a whole saving.

It is likely that only a fraction of the saving is realisable in productive gain, so the economic impact lower than suggested, and tube strikes do lead to a net loss for the economy.

Fewer tube strikes!

However, we humans are imperfect, and our productivity can be affected as much by mood as raw hours available to work, and if the tube strike results in people finding slightly more pleasant journeys to work, that emotional benefit is likely to be harder to measure, but probably more valuable to our emotional being.

For example, I could cut about 3 minutes off my commute to work, but I know an alternative route that guarantees me a seat (Aldgate vs Aldgate East) — so I walk a little further to a different tube station so that my commute is more pleasant, and I arrive at work less disgruntled than had I been standing most of the way there.

I have irrationally valued comfort over time saved, but I am likely to be more productive in the office as a result of being in a better mood.

That’s an economic impact that’s harder to measure.

However, there is a side to this which does affect comfort, and that was shown up during the 2012 Olympics, when people were exhorted to avoid commuting if possible. That change in behaviour resulted in a capacity gain across the tube network of around 10%, or an entire Crossrail.

People changing work patterns and commutes made the commute more pleasant for everyone else. So strikes probably don’t lead to a net economic benefit, and on the day annoy a lot of people — but the long term benefit may well be an ever so slightly more pleasant commute, for everyone.

Larcom, Shaun, Ferdinand Rauch and Tim Willems (2015), “The Benefits of Forced Experimentation: Striking Evidence from the London Underground Network”, University of Oxford Working Paper.

The full report (minus some charts) can be found here, via press release.

Canary Wharf is a lot further away from the Jubilee than Heron Quays and, indeed, the announcement on a DLR train as it pulls into Heron Quays says to change here for the Jubilee line.

As we should know, it is not geographically accurate, and the distortion effect is greatest as you get closer to the centre.

Classic example, with a line that, disgracefully is not shown on the “tube” map ….the central section of Thameslink:

W Hampstead – Elephant & Castle.

And, of course, the line that vanished, but is still open:

Finsbury Park – Moorgate

Interesting idea ….

it would also help if the TFL journey planner gave better route plans, when I plan a journey these days I usually check for what time I have to leave home usually but if I’m going somewhere new I do a quick plan but often it gives one choice only bus use and one choice of combined travel and its not always the quickest or easiest.