Today marks the 50th anniversary of an agreement between the French and British governments to build a tunnel under the English Channel to link the two countries.

No, it hasn’t been 50 years since Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister, this was one of several aborted attempts to dig a tunnel under the sea, although it got somewhat further than most previous attempts.

Announced by Mr Marples, the Minister of Transport on the 6th February 1964 following meetings with his counterpart in France, the tunnel was estimated to cost around £160-£170 million on then estimates.

“There are many problems to be solved, but in principle, we have decided it is a good thing,” the Minister told Parliament.

However, the date of starting construction, and indeed who would pay for it were still undecided. While generally presumed to be a state operation, there was a stock market listed company, the Channel Tunnel Company, which jumped on the news. That company had been formed in 1881 to built the first attempt under the sea and was still technically solvent. Somehow.

Also, the governments were still deciding between boring a tunnel, or dredging a trench and laying the tunnel in segments within. A geological survey was called for, and over the next couple of years, hundreds of boreholes were drilled into the sea bed to see what was down there.

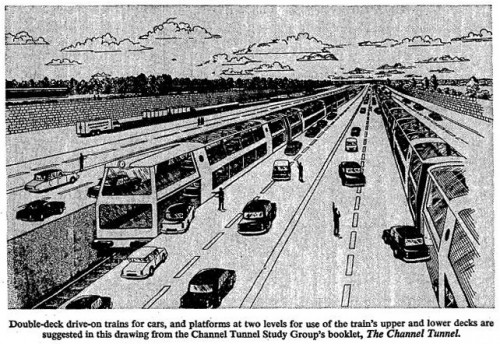

Within days though, different interest groups were vying for attention. British Rail said they were very supportive of a rail-based tunnel, while the Times motoring correspondent noted how a car-carrying rail tunnel could spur motorway construction in the UK — which was still seen as a good thing then.

Another person to spot the commercial implications — with the ink barely dry on the agreement between the two governments, an advert appeared in The Times.

As usual, the French press was rather more enthusiastic about the tunnel than their British counterparts.

Less keen on government funding also was a private consortium who said they could raise the money and build the tunnel by 1970 if permitted. We should recall that this was still a time of considerable government ownership of industry, and the idea of a private company building such a thing was seen as a bit too American. A view which wasn’t helped by the fact that the Channel Tunnel Study Group was backed by Americans!

Undeterred the governments pressed on, and surveys were agreed to start in the summer of 1964.

That autumn, our Mr Marples and his French counterpart, M. Marc Jacquet met in the English Channel and watched the drilling underway. They suggested that the tunnel could be completed within a decade — opening therefore around 1974.

Work continued, and the following April, a written reply to a question in Parliament showed that the drilling work was progressing well, but it would be at least the end of the year before it was completed.

In fact, the governments on both sides started to come under pressure soon after to start preparatory work immediately as they had enough to make a start on the broad outline of the tunnel.

And it was to be a tunnel, not a dredged trench.

Then as today, great construction projects can sometimes be derailed by economic headwinds, and there was starting to be concern about whether the government could afford to build the tunnel at all.

Towards the end of 1965, MPs were increasingly seeking and receiving assurances that the tunnel was not subject to the same curbs on government spending that other departments were facing.

They still expected that construction would start within a year, and be completed within 5 years. The budget was still expected to be in the region of £160 million.

But doubts were starting to emerge

An otherwise seemingly favourable joint statement by both governments in July 1966 seemed hedged with a lot of caveats and uncertainties. The Times even published an editorial asking if the tunnel is still wanted.

However, progress marched on, and at the end of October 1966, the redoubtable Mrs Barbara Castle and her French counterpart, M Pisani decided to bring in private finance to fund the tunnel.

“I cannot say definitely that the Channel tunnel will be built,” Mrs Castle said, ” But it is the aim of both governments that it should be,”

But, the future of the tunnel now hung upon whether private investors were willing to pay for it.

Now that the government seemed to be trying to extract itself from the project, the government-owned British Railways, once so supportive of the project also got cold feet about it.

They felt cargo ships would offer cheaper alternatives to the tunnel, and started warning investors that they might not want to use it come 1975 when the tunnel was still expected to be opened. British Rail pushed ahead with its own sea cargo facilities at Harwich.

Nonetheless, banking groups started to line up to raise £200 million to fund the tunnel, with three groups announced by the following April.

By the following January, in 1968, things were looking gloomy. The cost had reportedly risen to £250 million, at least — and while denied by the government, there was speculation that the project was to be axed.

Even the French didn’t seem that keen anymore.

A surprise amendment to the Transport Bill in May 1968 saw the government set up an independent committee to oversee the tunnel project. By July they still hadn’t decided which of the three private groups would get the contract to build the tunnel.

And delayed again in October until at least Spring 1969 as the cost rose again to £350 million. The following July, still no decision, and talk of the project costing £500-£600 million, although the government still stuck to the £350 million figure.

We’re into early 1970 now, and the three banking groups are talking about a merger so as to try and force the issue and get the government contract signed at last. Come May 1970, and the Minister of Transport, Mr Mully finally admitted that a decision won’t be taken until 1972, or later, and construction won’t even start until 1977, or later.

Ominously, he made the announcement when opening an expansion of the Dover car ferry terminal.

In Jan 1971, the government commissioned yet another study into the tunnel project, and while openly supportive, in government, commissioning studies is a useful way of slowly finding an excuse to kill off a project.

A decision was pencilled in for some time in 1972. When it arrived, unsurprisingly, it was generally unfavourable. The tunnel was now expected to cost at least £500 million, and traffic would be lower than earlier predicted.

Both governments met in August, not to decide on the tunnel, but to discuss a final survey of the project. They agreed to allocate more funding for more studies. More kicking into the ever-lengthening grass.

As an aside, while all this was going on, the GLC in London was wondering where the London terminus would go. They looked at a number of options, including Victoria, although either Surrey Docks or White City were favoured due to the job creations they could offer those areas.

In March 1973, the report was finally published, but a final decision was now pushed back to the end of 1975, at the earliest. They would still be deciding if they would go ahead in the year the tunnel was supposed to have opened to its first passengers.

Oh, and the cost had risen to at least £800 million.

A signing ceremony between the two governments for the final project in June 1973 was delayed.

Oh, and the cost was now being put at £1.1 billion.

Come September, and the government was still publicly supportive of the project, which they expected to be completed by 1980. An interim bill was proposed to keep the project ticking over while MPs “considered at more leisure” the final hybrid bill that would bring the Channel Tunnel into being.

At last a treaty!

In November 1973, British Prime Minister Heath and French President Pompidou signed an agreement to push ahead with the tunnel. Work actually started within days — as the pilot “chunnel” was started at the end of November — almost exactly 100 years after the last tunnel between the two countries had been started.

But the project was now dogged by ever more vocal concerns about the rising cost in an age of austerity. A suspiciously large number of news articles were appearing scaremongering about traffic jams, fires and the like, all caused by the tunnel.

Political problems also rose, as MPs debated the bill before them throughout late 1974. As part of the cost savings, the high-speed rail link from Folkestone to White City in London was dropped as too expensive.

On Dec 10th 1974, the French government proposed that the project be “paused” at midnight on the 31st December.

The project was effectively dead.

The government set aside £15.6 million to cover the costs of what had been built so far. Some very 1970s era photos of that tunnel construction work can be found here.

It was formally killed on Jan 20th 1975, when the Secretary of State for Environment, Mr Crossland made a statement to the House of Commons, citing rising inflation, rising costs and shrinking traffic forecasts.

Although the French had asked for another delay to keep the project limping on a little longer, the British were simply not interested.

And so the situation was to remain, with a constant trickle of ideas and calls for the tunnel to be resumed until finally the current Chunnel was agreed in 1987, and opened in 1994

The cost having since risen to £4.65 billion (equivalent to £12 billion today).

Oh, and that little bit of tunnel dug in 1974 — that was reused as the starting and access point for tunnelling operations from the British side for today’s tunnel.

So it wasn’t a total waste after all.

Fascinating. It gives hope to us in Australia who would like to see a high speed train travel between from Brisbane through Sydney and Canberra to Melbourne.

See my first thought on all this ended up being “So how did the Channel Tunnel Company survive so long, and what eventually happened to it?”

I am not entirely sure about that company, but it is on my research list.

We have the Channel Tunnel Association archive here in Special Collections at Brunel University, which includes the Channel Tunnel Company archive.

The link to the 1970s construction photos is now broken, but they can still be seen at https://web.archive.org/web/20160113125041/http://www.du.kent-history.co.uk/1/tales/74.htm