Today marks the 75th anniversary of the great fire that destroyed the Crystal Palace, an ill fated “shopping center” that had long since fallen on hard times and finally met its knackers yard in a blazing inferno.

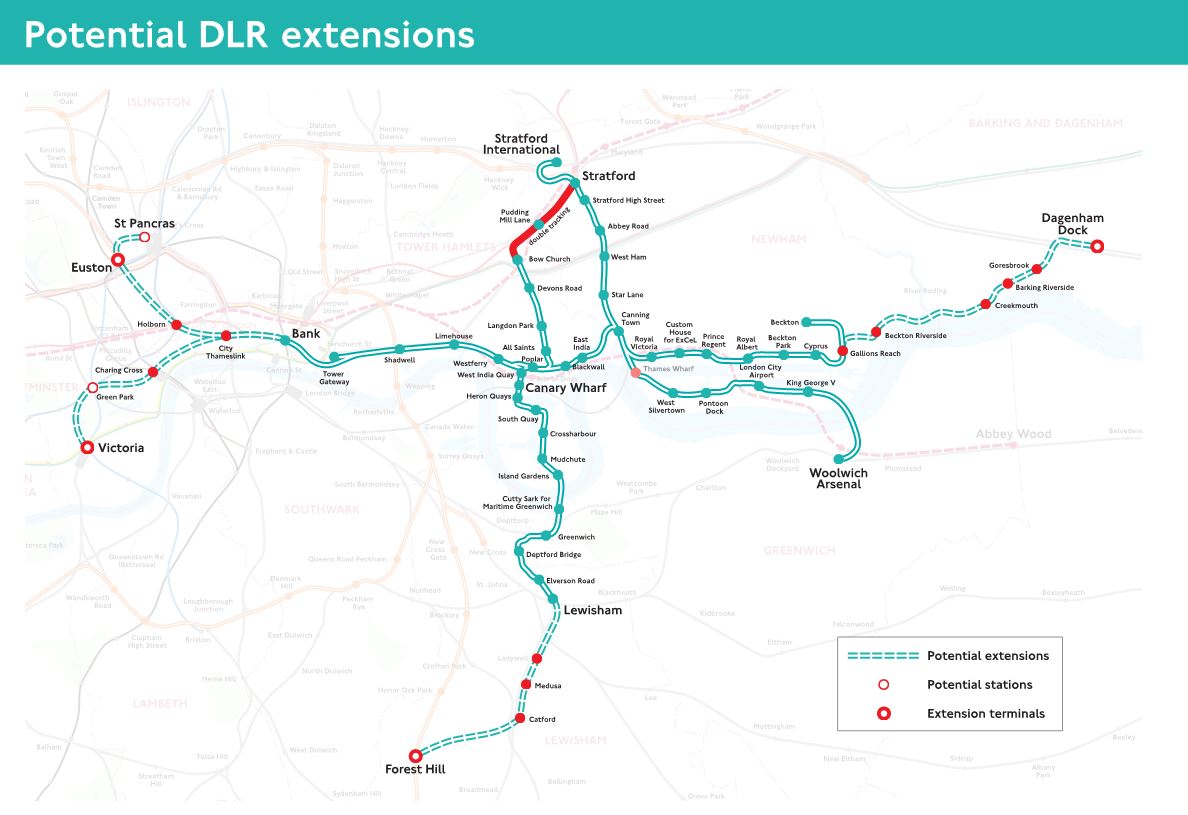

Although set up in Hyde Park as an exhibition, when moved to Sydenham it was as to be set up as their version of today’s Westfield – a giant shopping centre that aims to act as an attraction in its own right. Indeed, just like Westfield Stratford, when the Crystal Palace was rebuilt, it came with its own railway stations.

The company that moved the building to Sydenham was burdened by a massive debt, and was initially unable to open on Sundays, so revenues were never enough to cover the debt costs. The company finally declared bankruptcy one hundred years ago – in 1911.

Repurchased for the nation by public donations, it was used during WW1 by the army, and was under restoration when on 30 November 1936, the whole building was destroyed in a fire that was reportedly visible across most of London.

The site is still derelict.

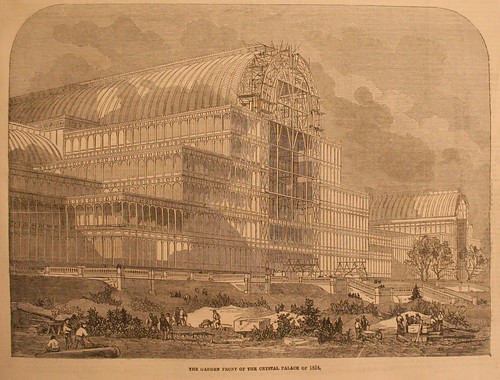

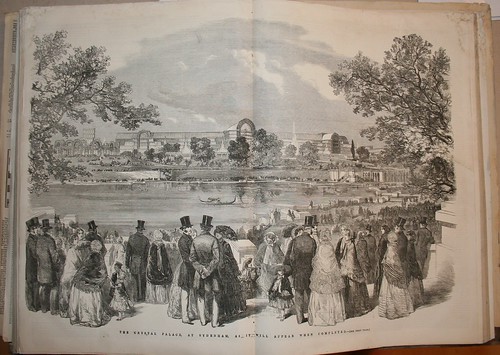

Lets jump back though, to Saturday April 22nd, 1854 – as the Crystal Palace is nearing the final stages of its move to Sydenham, and the Illustrated London News sent a journalist along to report on the rebuilding works.

The following is from my collection of the Illustrated London News

PROGRESS OF THE CRYSTAL PALACE.

Let us imagine a journey by the separate line of rails which now extends complete, and will in a month be open to the public, from London-bridge to the Crystal Palace — a line exclusively devoted to what, to coin a word, we must call Crystal Traffic.

Arrived at the foot of the South Wing which forms a sort of supplementary station to a brick and slate station, almost concealed by banks of earth and trees — we pause upon the steps, and, looking up, see before and above the far-extended towering mass, which rises before us in form and proportion quite unlike anything we have seen before.

Our readers — making allowance for the conquests of working days, and warm spring time, between the hour when Mr. Philip Delamotte set his sun picture-manufacturing machine to work and from that sun painting our Illustration was drawn and engraved — must imagine the scaffolding removed; the broad terrace smooth and clear — green turf in the place of the tram-way; the trees budding; and the distant balustrade crowned here and there with marble statues.

We must leave to be told by our pictures the vast difference which exits between the hasty, hurried sketch by which Paxton saved the first Exhibition from suffocation beneath brick and mortar, and this, the matured result of time experience, and the just confidence his genius has earned.

As to the series of Courts, as long as the art department of the interior is incomplete, it is premature to criticise details; for details cannot be fairly judged until seen with the accessories of colour and adornment for which they were planned. We will, therefore, after entering the building by the basement, ascend to the Central Transept, and turn our steps to the southern arm of the Palace. It will be difficult for upholsterer’s ornamentative taste — as seen in the last George’s reign, in Long Wellesley’s solid gold cornices, and Lord Harborough’s Green-park paling, with its gilt nails — to survive the lesson of the series of Courts.

Pleased with the general plan; seeing in the details an admirable lesson in taste, in form and colour, in what to imitate and what to avoid, for the rising generation of workers and of patrons; with all our admiration, we cannot help fearing that the directors of these departments in their anxiety to provide copies of the best works of sculpturea in all ages, have run the chance of crowding up the space with plaster casts, which, however valuable to art students, will soon became wearying to the multitude.

The fine vista., the rich colouring, the beautiful details, the historical, theological, and poetical associations of the two series of Courts will unite the suffrages of all classes of visitors; but the plaster images from the work of known and unknown artists, and the long lines of busts of worthies, illustrious and obscure — from Alexander the Great to the Texian patriot, Colonel Ringtail Roarer, from Homer to the celebrated Senator Squabbs, of Little Pedlington — will be found not very attractive out of a small circle of enthusiasts, which does not increase.

People of all orders, educated and uneducated. never tire of trees and flowers, green turf, flowing water, of the gambols of parti-coloured carp. The changes of light and shade always afford some new picturesque effects in a ran harmonious building like the Crystal Palace; but a few statues in marble are enough for one day — a long regiment of plaster becomes wearyingly monotonous and harsh.

The Court of the Byzantine age i almost clear of the modeler;: and the decorators have done enough of their work of flower and grotesque tracery, on golden ground, with coloured marbles, or undiscoverable imitations of coloured marble, to give a fair idea of what were the best works of the age extant when the Turks took Constantinople, and turned St. Sophia into a mosque. The next Court, the Mediaeval, is still suffering severely from the strike of the plasterers: rich fragments of church architecture, unfinished, and bare laths, that are to grow into gained and fretted roods, bid us pass on to the Renaissance Court, where the decoration of the walls is proceeding with satisfactory zeal. We pause before the gates of Ghiberti, and rejoice that the copyist’s art has given us all the pleasure of the originals, without robbing Florence and Florence robbed Pisa.

Turning from schools of art and architecture, botany, geography, and ethnology, to be hereafter described in detail, we enter the Southern Division, and Commercial Department, which, whether considered, as a source of amusement and revenue, or as living epitome of the trade of the world, will certainly, if judiciously managed, become one of the most important, because of the most original, and universally interesting parts of the undertaking.

The Southern Wing or nave is flanked on either hand by a series of square courts, destined for the special display of particular manufactures.

The first on the right hand, looking south, is meant for Stationery goods of all kinds — books, prints, and ornamental work in paper and card. Built from plans and designs by Mr. Craze, it will show what can be done with wood and plaster no disguised to imitate stone or brick, but in their genuine forms: the plaster coloured, with various shades of ochre, and other earth colours; and the beams and panels of wood, representing the ornamental use of wood imitated in grain and texture with perfect fidelity. Of the results, it is impossible to say anything at present; but at any rate it will be quite new. In this, as in several other of the coart, medallions and frieze will represent the progress of’ the arts connected with the goods to be there exhibited. As, for instance, paper manufacture from the papyrus leaves joined with the mud of Old Nile, to the instantaneous bleaching, tearing, washing, drying process, which converts old rags and cotton waste into the new material for printers’ presses, authors’ pens and artists’ brushes. Caxton, whose English labours it was found impossible to commemorate by a gas lamp and a fountain in Westminseter will, doubtless, have a bust, if not a bas relief. Lithography will net be forgotten. The stone quarry will afford its pictures, and the flax field its emblems.

The Birmingham and Sheffield Courts, whose names bespeak their contents, follow on the same side; while, in the corridor behind, hardware, not manufactured in either of those towns, will be arranged on the floor or counter, and on the walls. The two Courts of the Hardware towns will be much more ornamental in their contents than might be imagined by the uninitiated from their names. On their walls the miscellaneous articles going under the general name of steel toys and gilt toys will be displayed in picturesque shapes.

Scissors are a tolerably commonplace article, according to common notions; but the variety of scissors made in Sheffield, both for home use and export, afford room for devices not less attractive than the ornaments of the antechamber of a military Prince, or the cabin of the fashionable Captain of a crack frigate. For instance, the scissors manufactured for the use of Turkish ladies, used by them chiefly in cutting long rolls of Turkish paper into convenient strips, are, when closed magnificant daggers, with gilt handles richly moulded. The Exhibition of 1851 showed us how ornamental stoves in steel, or-mculu, and tessellate tiles, arranged from the designs of artists, could be made. The Sheffield Court, designed by Mr. G. H Stokes, will bring to its adornment the works of the best manufacturers in a town where the art of design has made decided progress. We ought to see, not only the celebrated enduring Sheffield plate and electrotype, but some specimens of real silver and silver-gilt plate, which, after Wing made in Sheffield, appears very often under the character of Landon West-end manufacture.

The Birmingham Court, entered by ornamental Iron Gates, opening to the Nave, will have materials for display not inferior to Sheffield, in all the papier mache, in iron, in steel, in brass, in gilt, in all that makes an English house comfortable, or cultivates an Indian plantation, or cooks a Spanish dinner. Birmingham, besides those articles in which a fair rivalry is carried on with Sheffield, makes a greater variety of useful and ornamental articles in steel, brass, and iron, than other town — from lamps to spades, from swords to machetes; or Indian hoes;; rings for lassos and the noses of negro Princesses; guns of all vaues, from the costly rifle or smooth bore, with which a Pallitser or a Gordon Cumming extirpates the lion of Africa or the grizzly bear of the Western Prairies, to the seven shilling musket, which keen lemon-coloured African Captain barters with coal-black King Qussshie for palm-oil and ivory — slave prisoners being no longer a merchantable commodity.

Fire-arms, we understand, will not occupy any of the space in the Birmingham Court, but a special section will be set apart for them; and there, side by side with his American and Belgian rivals, the Birmingham gun-maker will be able to set up specimens of the quality, and statements of the price at which he is prepared to supply the fire-arms for a European War; probably, this section of the Exhibition will do more to settle the question of Government manufacture or private enterprise for the arming of our regiments than any number of Parliamentary Committees. We can only say that if a Government manufactory can turn out rifles mid muskets cheaper and better than private individuals, it will be an exception to Government transactions in Public Works of any kind, front the Docks of Pembroke to the Kennington-park; which last has taken more time to plan than the Park of the Crystal Palace, and in still flat, dreary, unplanted, and unfinished. One interesting feature of these Birmingham and Sheffield Courts is the opportunity afforded to ingenious workmen of exhibiting small inventions patented under the new law, or original designs, or specimens of superior workmanship, by hiring a single square foot or so, from a kind of margin reserved round the cases that ornament the counters, at a small annual rent. This will be a great boon to the inventors and designers among the hard-handed, who form so numerous a class in the hardware towns.

The Pompeian Court, which we described in our notice of the Queen’s visit, completes the series on the West Side of the Nave. The East Side is flanked by the Court of Musical Instruments, in which manufacturers of pianos and substitutes for organs and other large instruments have engaged space. It is to be hoped that an arrangement as harmonious a the architect’s design may be made with the exhibitors; if not, how distracting the concerts of enraged rival musicians, when the grand, the cottage, the piccolo, mingle without combining, with the trombones, cornets-a-pistoas, ophicleldes, and other fearful instruments of wind and string, which are to fill up windows specially planned for their display. Music-books will be found in the Stationery Court. Two Courts — one intended for Printed Fabrics, and the other for Textiles of Wool and Silk — follow next ; the series is completed by a Foreign Court, intended to receive the choicest productions of France and Germany.

The Printed Fabric Court, deigned by Mr. Barry, a son of Sir Charles, and the Mixed Fabric Court, by Professor Semper, the architect of the splendid theatre and the museum at Dresden, may be said to consist of a novel arrangement of plate-glass windows, and cases adorned with emblematic devices. The statue, of Manchester will crowns the Printed Fabric Court, and reign over friezes and medallions representing the rise, the prgress, the triumph of cotton wool from the Indian distaff spinning on the floor to the self-acting mule, and other inventions, by which Cartwright, Hargreaves, Roberts, and a crowd of obscure ingenious men have enabled the humblest labourer to indulge in a weekly clean shirt and clean pair of sheets, luxuries unknown to Norman Barons; which has made cotton stockings a necessary, and rendered it possible to discard the long-worn woollen garments, which, when body linen was unknown and soap dear, were the perpetual source of pesilential disease among the poorer classes. Something very pretty might be designed on the subject of chintz and calico printing. We wonder whether, in less warlike times, the architects would have given a medallion of Richard Cobden, whose Free-trade 1abours were sustained by his successful dyes and colour-printing processes.

We have not learned what symbols and ornaments Professor Semper means to use in his Court ; but the lama ought not to be forgotten, or the Peruvian weavers of ponchos of wool, adorned with coloured designs, which even now form the best patterns for the South American market, and bears a strange resemblance to those of Indian looms. After the wool of the lama, and its kindred tribes, the alpaca and vicuna, had been neglected for centuries, it was reserved for an Englishman, Mr. Titus Salt, to discover its value, and devise processes of manufacture, in which no country can at present compete with us. France, Italy, India and China rival us in silks, Switzerland in cottons, and Belgium and France in merinos and fine cloths; but the beautiful results of a mixture of hair, wool, silk, and cotton, are only to be found in perfection in Yorkshire.

Other animals, besides the lama tribe, have a fitting place in the symbolism of mixed fabrics. For instance, the camel, the Cashmere, the Angora, the Syrian goat ; the sheep, feeding on the fat pastures of Leicestershire, or nibbling the short, sweet herbage of the South Downs, or facing winter on the heather of Highland or Welsh mountains, or the moors where the Exe rises — the diminutive breed found in Shetland and Iceland, or the noble stock which, proceeding from Spanish plains, found its contraband way to the covered sheepyards of Saxony and Russia and were there transplanted to give golden value to the Bush of Australia. Truly, when we summon up all these and many other tribes and varieties of the woolly and hairy race, which are appreciated in Leeds, in Bradford, in Halifax, in Huddersfield, and have created the model town of Saltaria, we feel that the Crystal Palace Directors would have done well to engage some of our animal painters to give assistance to the distinguished architects they have employed.

Ascending from the floor of the Nave to the Gallery by one of the many staircases, we find almost the whole space given up to the display of manufactured goods ; below, architecture, sculpture, trees, flowers, and fountains, and a few choice blocks for special manufactures, rented at a great price ; above, we enter a more serious bazaar, to which some of the best men of all trades I have contributed : at one extremity, tailors, hatters, shirt-makers, bootmakers., and all that goes to clothe the European man ; at the other, china and glass, English, foreign, European, and Indian.

The Galleries of the Great Transept are fitted up to receive precious metals, fine jewellery, and precious stones ; while, in appropriate situations, photography and perfumery, philosophical instruments and Indian rubber, leather and cutlery, will be displayed, priced, and sold to those who choose to combine the pleasure of shopping with the pleasures of art or of idleness.

It is the manner in which the Sydenham Exhibition accommodates itself to the many-sided tastes of the multitude that gives the best prospect of the success of so gigantic an undertaking. The power which exhibitors at Sydenham will have of opening a large or a small shop. of being wholesale or retail, of setting up their names and addresses, of fixing the prices of their goods, of attending to make sates and take orders, will secure a living interest, a constant change of the articles displayed, and a degree of publicity greater than that of the Boulevards and arcades of the Continent, or the fashionable streets of London. The advantages in what may be plainly called the advertising point of view, are obvious, as also as a bazaar or display of a collection of samples of the best or the cheapest manufactures of the world. This b the theory of the under-taking; the practical success will depend on whether the plant; of the directors, being based upon the common sense of commerce, are carried out by the officers of the company with due regard to the habits and prejudices of manufacturers and shopkeepers ; above all, with courtesy, and as little as possible of that brusque official manner which seems chronic in the servants of Governments and public companies.

We can imagine, under a judicious arrangement, specimens of never-failing genus, the new-married couple, not only spending hours of honeymoon in the lounging through the Art Courts, or resting in the Gardens, but, in more domestic mood, discusing, criticising, and selecting the whole furniture of a house, from the kitchen to the attics, from the beehive to the garden tools, without leaving the Crystal Palace Company’s premises. Looking into the iron gates of the Birmingham Court for the tea-service, the coal scuttles, and the saucepans ; to Sheffield for the knives, spoons and forks ; to the Printed Goods Department for curtains ; and to the Woollen Department for carpets of Kidderminster, or Halifax, or Aubuson. Then, mounting the Gallery for china and glass, or Bohamian chimney ornaments ; or descending to the Nave for mirrors ; or to the Basement, to see a heavy kitchen-range or a patent mangle. The husband going to the North Wing to selec t agricultural implements for his fancy farm; or the wife making a critical survey of the South Wing, before deciding between a brougham and an open phaeton. Or we may conjure up a South American, or Australian, or a United States merchant making a preliminary survey of the samples at Sydenham of soft goods and hard goods, damasks, velvets, satins, files, scythes, cutlery, rifles, cutlasses, and gilt beads, before travelling to Sheffield, to Birmingham, or to Leeds. All this is possible from the space at the disposal of the Company, from the attentions offered to visitors, and from the character of the manufacturers who have contracted to send their goods there. Whether it will be realised depends not on theory, but on practice. Amongst other aids to the Commercial Department, a Directory will be issued containing the name and full particulars of the calling and goods of each Exhibitor, so that Purchasers will have no difficulty in finding out the where and what they need.

The foundation of success rests on the managers of an undertaking an entirely novel character, adapting it to the spirit of an age of steam locomotion, electric telegraphs, and cheap postage. If they can manam to combine instruction and amusement with the transaction of a large amount of concentrated business, then the gardens and fountains, the statues and galleries, will be easily supported in at least their original freshness and splendour by the profits of a World Fair, an ever-changing school of manufacturing art and skill.

What a fascinating read – particularly the writer’s enthusiasm for scissors and sheep over statuary!

An interesting snippet about the Crystal Palace is that when it was relocated to Sydenham from Hyde Park, one of the cast iron posts apparently somehow ended up at Holme Fen in Cambridgeshire (now a fantastic National Nature Reserve of birch/oak woodland and fenland) and was driven into the ground to its full depth. As the peat soil has shrunk over the years (due to agricultural drainage of the previously waterlogged soil which has allowed aerobic decomposition to begin), the post has been fully exposed, evidence of a drop in ground level of around 4 metres in the intervening 150 years. Look at the OS map of the area and you will see that the elevation/spot height here has a negative value – Holme Fen is the lowest point in England at about 2-3m below sea level. So presumably, if the sea were ever to inundate the Fens, the top of the post would just be visible above the lapping waters.

http://www.naturalengland.org.uk/ourwork/conservation/geodiversity/englands/sites/local_ID7.aspx

There are some other columns/ironwork in Crystal Palace Park, but these are replicas as far as I’m aware. I wonder whether any more of Paxton’s original iron work was salvaged after the fire, hidden away in someone’s shed or garage, as parts of the Skylon are reputed to be?

My father remembers seeing it burn down from many miles away – aged 7.

A poor comparison to Westfield. It was never a “shopping centre” but rather a impressively large glass conservatory housing many exotic plants while displaying many types of architecture from around the world. To say it was a shopping centre is an insult. I advise you to read into the history of Crystal Palace to get a further understatnding of what it truly housed

A strange and fascinating anniversary — have a look at this eyewitness account of the fire on my website.