Over the years, there have been many attempts to build something above South Kensington tube station, from modest to grandiose. How different would South Kensington look today if previous plans for hotels and shopping centres had gone ahead?

There have been plans for hotels, huge office blocks, shopping centres, total demolition, partial reuse, all sorts of plans. And some of them even secured planning permission to be built, only to fail to get started because of financial problems.

But, as you will learn, part of one of the schemes did get built, and to this day, thousands of people walk past it, not knowing that they are looking at part of an unbuilt hotel, right in the middle of the tube station.

The site of the tube station should have a lot of potential, as it’s a sub-surface station in a cutting that looks like it could easily be built over again, and that large amount of airspace is as much a lure to London Underground who wants to develop it, as it turns out to be a problem to actually build over.

So many plans have been proposed, some approved, many not.

Here’s an abridged countdown of the biggest baddest plans for South Kensington station.

1950s – Ivor Shaw

This is the earliest substantive scheme I can find, dating to February 1956 when the architect, Ivor Shaw sent an outline proposal for an 8-storey office development above the station, said that they had at least one potential tenant seeking 200,000 st ft office space away from the West End to avoid worsening road congestion.

However, a report for the council a month later recommended rejection as “not in accordance with the County Development Plans” as regards usage zoning of the area. South Kensington is residential, and putting offices in the area went against a government policy at the time, which was to actively reduce the number of new offices in London. This was to support the prevailing opinion at the time that London was to shrink as a city and people would move to the suburbs and new towns instead.

The scheme was refused permission on 19th Nov 1959.

1960s – Carl Fisher & Associates

A proposal by Carl Fisher & Associates in Dec 1959 was for two tower blocks for nearly 100 flats, shops and garages, all set further back from the front of the tube station. This was still the age of the motorist, so 30 garages were included as you couldn’t really expect “the man of the house” to go without a car.

The council was supportive, in principle, if daylight concerns to neighbouring properties could be addressed, and planning approval was granted on 10th June 1960, for a concrete raft to be built above the station, and the oversite development to go ahead.

The development never took place though, and the planning permission lapsed.

In June 1966, proposals for a complete rebuild of the tube station were put forward, which would have seen everything above ground flattened and replaced with a huge hotel.

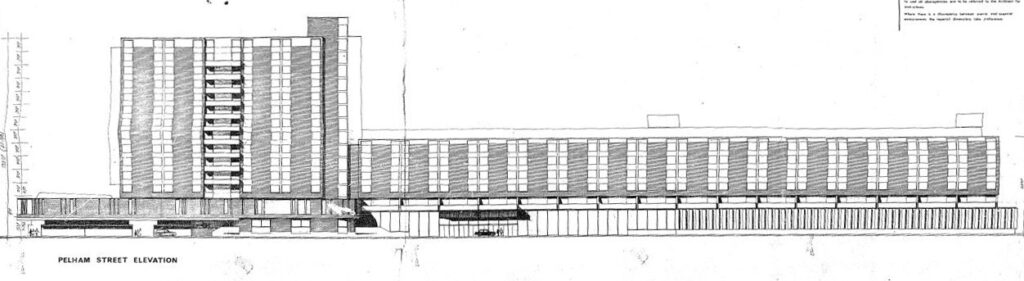

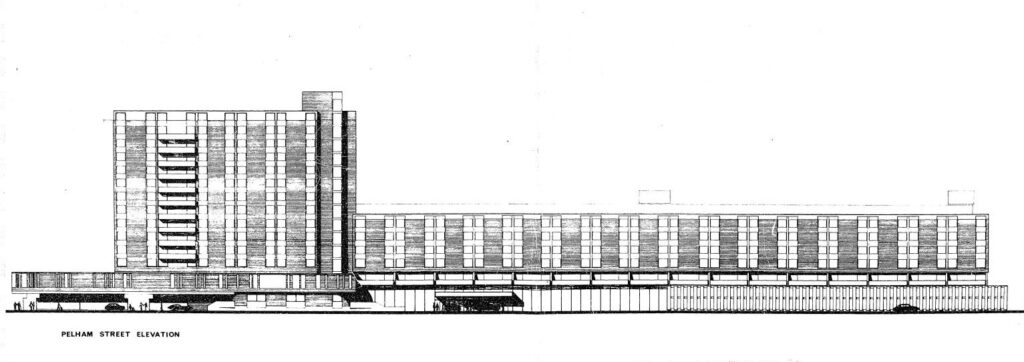

A hexagonal tower would sit where the bullnose is today, with a long low-rise block running above the station, and a second tower at the far end.

A revised scheme was submitted in February 1968 reducing the height of the tower blocks, and converting the planned flats into hotel accommodation for 521 bedrooms and 200 car parking spaces.

The motivation was to cater for ‘potential “jumbo jet” passengers who will be in London for a relatively short period of time’. This was the beginning of mass tourism which we take for granted today, but didn’t exist at the time, and hotels served the rich who could afford to travel for months at a time. With cheaper flights, the week-long holiday was born, and so was the need for large qualities of cheaper hotel rooms.

The plans for the hotel would see it have an entrance on Pelham Street, with the car park entrance on Thurloe Street.

The plans were not well received, and the following year, in March 1969, the developers were back with an amended scheme, with an 18-storey tower, later reduced to 12-storeys and a 6-storey block behind, for hotel, shops and car parking.

That would have still given them 515 rooms though, a substantial number for the time, and the size of the development continued to provoke protests. The London Correspondent of the Washington Post wrote in opposition to this “astonishing” scheme and said that it would render South Kensington no different from New York.

At a council meeting in May 1968, concerns were raised about road traffic congestion, especially coach arrivals and volumes of people arriving for ballroom events. A later review by the council concluded that traffic volumes would be acceptable within the existing one-way road layout.

A pre-application meeting in Nov 1968 proposed to change the height of the main tower from 12 to 13 storeys, and discussed an option to raise it to 18 storeys, with a reduction in height of an adjacent block. Following this, the council granted outline planning approval for the hotel to be built in October 1969, and that sparked a huge number of letters of objection from people claiming to have not known about the development.

The formal application with the final details for the design was filed in September 1970, and this triggered another wave of objections.

One rather bombastic opposition letter said that “artistic considerations do not weigh heavily with your council”, which was hardly likely to warm the council officer to the objector. Most of the objections were less to do with the design though, and a mix of concern about the size of the building and the increased road traffic it would encourage.

The Fine Arts Commission also weighed in, noting that a hotel in principle was not a bad idea, but that this particular design was not suitable for the area stating that it fell “far below that required for so important a site”.

The scheme was withdrawn by the developer in November 1970 for reconsideration of the objections.

A revised scheme submitted a couple of months later was generally welcomed in terms of the change in design, but did not overcome the objections relating to the building size and increased road traffic. However, the council granted planning approval for the hotel on 9th February 1971, and for the hotel to receive a funding grant from the government that was available at the time for new hotels, it needed to be built by the end of 1973.

However, in February 1972, work hadn’t started, and there was talk of converting part of it into luxury flats for company executives, with a large amount of office space for their use. Following a lot of meetings though, the plan was shelved after the council expressed its objection.

While all this was going on, South Kensington station itself was getting a major rebuild as the lifts to the Piccadilly line were replaced with escalators, and the subsurface platforms were rebuilt to allow space for the staircase to the Piccadilly line and, less well known but you’ll hear about it later, other works in expectation of a hotel being built above the station.

Meanwhile, the hotel developers seemed to go very quiet, and there are a number of letters flying between people noting the absence of any work going on, or even communications from the architects.

In August 1973 a development, as the ownership of the company planning the hotel changed, and Atlific (Chelsea) Ltd was bought by Galliford Estates Ltd., who were interested in converting the development into residential homes and offices instead of a hotel.

They also said that construction work on the concrete raft above the tube station was to start shortly.

However, as nothing had been done by 22nd February 1974, the planning permission expired.

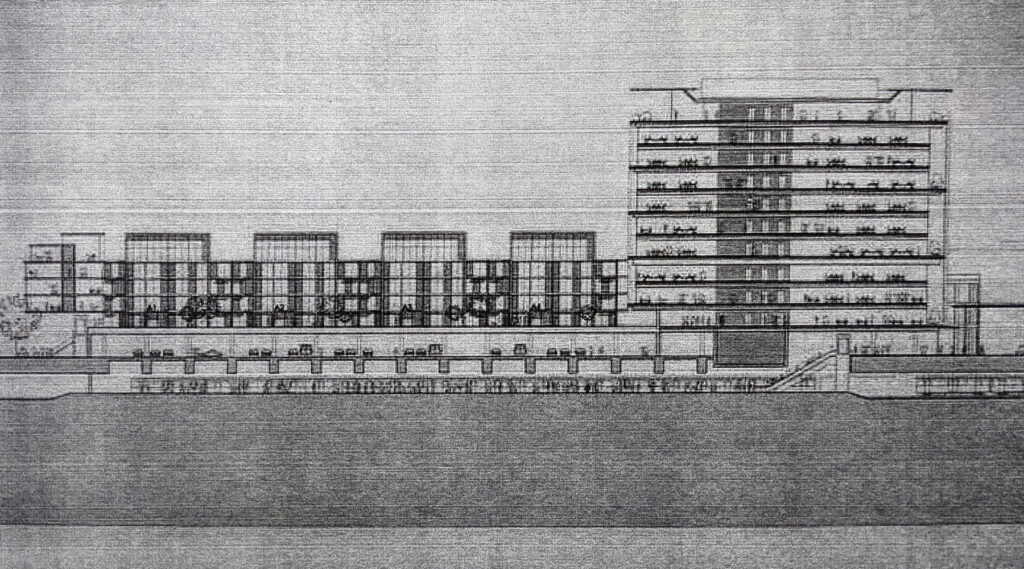

1980s – Scott Brownrigg & Turner

London Transport was back in January 1983 looking at the redevelopment of the tube station, and more detailed plans were announced in February 1984, with a call put out for public ideas for what could be built.

Proposals started being put to the council in September 1986, and the long process of finding a design that would be likely to get planning permission started.

In 1988, the firm, Scott Brownrigg & Turner was appointed to lead the design of the oversite development for a consortium of Tarmac, Rosehaugh, ATEC and London Underground. Their proposal was split into two sections, the bullnose development for commercial and office use, with the eastern end covered over to create residential flats.

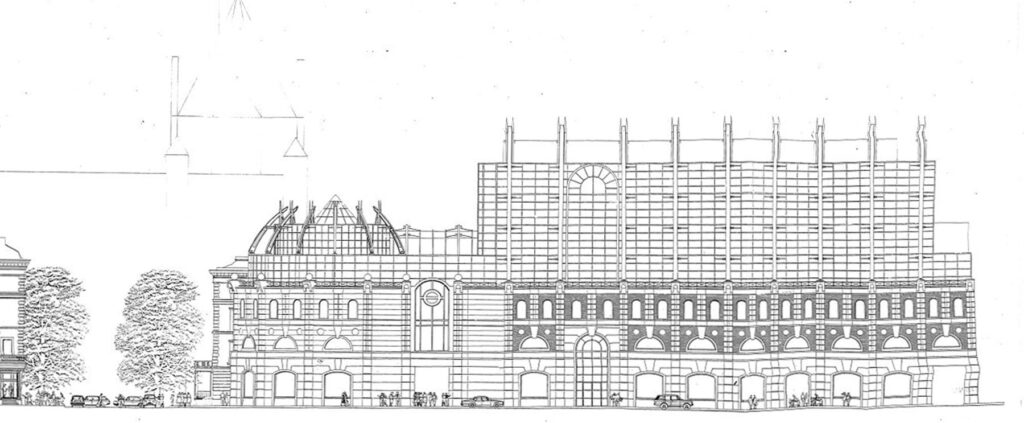

The commercial section would have created two floors for the tube station, 3 floors for shopping – representing a 10-fold increase over what’s currently there, and 4 floors for offices. Essentially, it was a giant 1980s style shopping centre and was to be called the “South Kensington Arcade”

Again, it provoked howls of protest from local organisations, again the development was seen as too large and likely to cause road traffic congestion. One choice letter of objection said that she didn’t object to the shopping aspect of the development, but objected to the “monstrous glass dinosaur” on top. Another choice response described the plans as “the half finished skeleton of some science fiction monster that simply collapsed under the weight of its own ugliness”

The plans were withdrawn in January 1990.

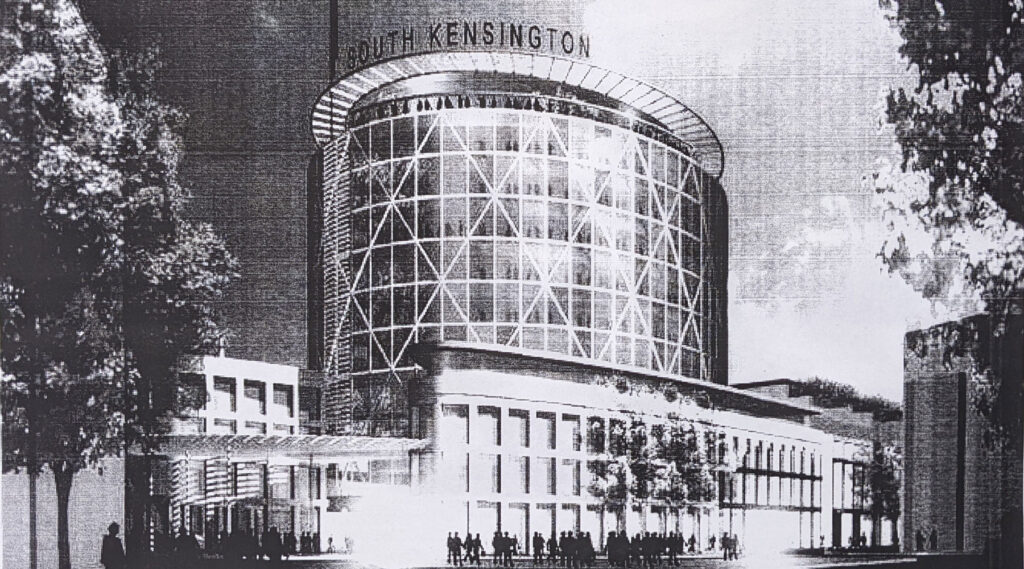

1990s – Terry Farrell Associates

In January 1991, it was announced by London Regional Transport that Terry Farrell Associates had been selected as the lead architect for the over site development.

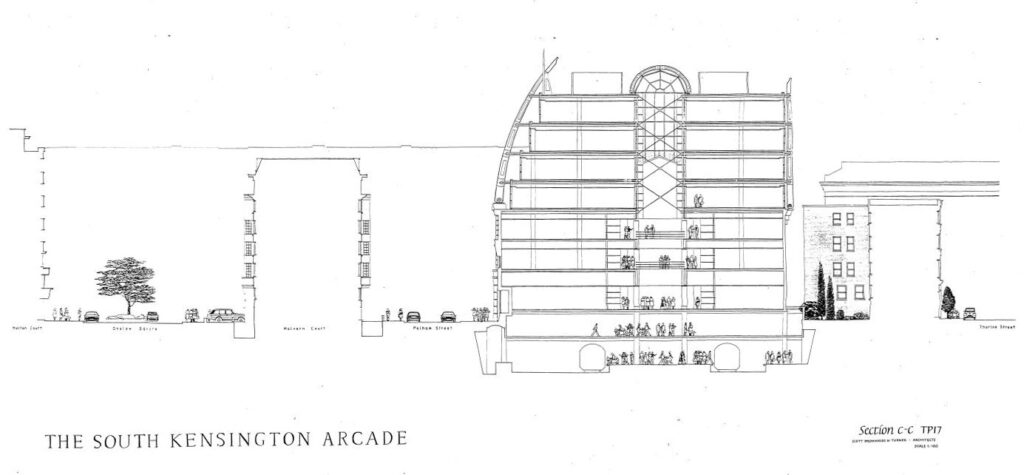

Initial thoughts were for shopping at the ground floor and lower or upper levels, and while the architects considered the relationship with Exhibition Road to be important, the bullnose was a negative corner with restricted access. Their proposal was dramatic as they completely rethought the entire station.

The bullnose would be retained in size, if not appearance. A long line of houses and offices would run down the currently vacant southern side of the building, but more significantly, they rebuilt the entire ticket hall. At the moment, the ticket hall is one floor below ground, but Farrell’s planned to move it up to the ground floor with a new round room leading off to new shopping arcades, and install new escalators to the platforms.

This would considerably improve accessibility and passenger flows through the station.

One of the more interesting changes that shifting the ticket hall to the street level is that it cut off access to the pedestrian tunnel leading to the museums, and there were a lot of letters discussing if it was possible to retain access, but the gist is that it would have considerably increased the cost of the development. So we nearly ended up with a disused tunnel.

Their proposal was to be seen as a collection of separate building elements, but required the demolition of the Victorian shopping arcade. That wasn’t as controversial at the time as it would be today as it wasn’t seen as a significant heritage asset. It was only granted historic listing protection in 2004, and today a developer wouldn’t dare to touch it.

But most dramatic was the tall round tower that would sit in the centre of the station above the new ticket hall.

With mainly commercial space at the western end, and a row of houses with a mews-style road running through the middle at the rear, in total, it would have offered 87 flats, a 5 storey office block, shops, restaurants and a new tube station entrance.

This proposal could, politely, be said to be less than popular with the locals.

In March 1993, a revised smaller scheme was put forward, which shrank the tall round tower so it was much lower in height, but compensated for the loss of floorspace by rebuilding the bullnose as a taller bullnose.

They also moved the revamped ticket hall deeper into the station under the smaller round tower and that also allowed them to reconnect with the subway link to the museums.

Concerns were now being expressed that the reduced size of the development meant it might not be commercially viable.

Again though, even in its shrunken state, it was the size of the development that was to prove the main issue for objections by local interest groups, although this time, it was the height of the residential properties along Pelham Street that seemed to generate the most letters of objection. However, at public exhibitions, the reverse happened, and the public tended to be more favourable of the scheme, compared to the objections from residents associations.

Even so, the council was also concerned about the size of the development. More revisions took place, restoring the Victorian frontage and some more modest changes. However, there was strong opposition to the plans with huge numbers of letters sent to complain, and several public meetings held to oppose the scheme.

The difficulty they faced was that in acceding to requests to shrink the size of the development also resulted in it no longer being economically viable. At one point a discussion took place as to whether it was worth continuing the development at a loss, as London Transport would take the long term view of the benefits to the station rebuild.

A review of the economics of the smaller plan was carried out in 1996, but even with optimistic assumptions, the reduced scheme was found to be unviable. A large part of the problem lay, as with most previous schemes, the need to build the large concrete raft over the station, the cost of which was a significant portion of the total cost of the project.

In fact, one document suggests that the cost of building the raft over the station would represent as much as a third of the total site cost. This was because the raft had to be made to far higher strengths than needed to support the buildings, just in case something very large and heavy was dropped during construction and punched through to the active station below. The only way to avoid that would have been to close the station entirely for a year to more while the main construction took place. Obviously not a viable option.

Although eventually approved by the council, the financials of the project were now too poor and it was never built.

(there were a few more ideas discussed between 2000-2015)

2016 – Buckley Gray Yeoman

Although it didn’t get to public consultation, this was much more modest than some previous ideas, avoiding the need to build the expensive raft over the top over the station, and getting away with a smaller amount of development. There would have been a row of modern houses to the south side of the station, a modestly enlarged bullnose, but more controversially, a rebuild of the row of shops and flats on the north side.

2020s – Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

We come to the scheme most recently rejected, which would have seen a row of modestly modern flats built along one side of the station, the Victorian shops and flats on the other built behind the retained facade, and again, the bullnose demolished and rebuilt with three floors instead of one.

Here they again attempted to avoid the problems of previous schemes which had to be large developments to cover the cost of the concrete raft over the station. By avoiding that cost, they could have smaller developments around the edges of the station.

The plans were rejected by the council in November 2021.

And finally, the bit that was built

If you head onto the subsurface platforms, you’ll notice a nice lightweight roof overhead with the classic cast-iron columns holding it up.

Hang on, what are those big square columns for then?

In fact, if you look closely, you’ll see that those big columns are not even touching the roof — they are the columns that would have held up the hotel planned to go above the station back in the 1970s.

During the rebuilding of the station for the escalator works in the 1970s, as London Transport expected something big and heavy to be going on top of the station, they decided it was a good idea to put in the foundation columns at the same time. They spent a fairly sizable £1 million (about £15 million today) on the foundation works and the columns that would be used to support a planned concrete raft above the station.

So every day, thousands of people walk past a row of support columns for a hotel that was never built. They’ve been there for 50 years, unloved and unnoticed waiting for someone to find a use for them.

Worth noting that Richard Rogers (of Rogers Stirk Harbour) died last week.

The scheme does seem to be fairly intractable. costs of building on or near railways are much higher and the locals are organised enough to object to anything big enough to justify it. I predict a re-invention of the Buckley Yeoman Gray-type scheme in 6 months.

Main driver for the hotel boom in the sixties was the government subsidy of £1000 per new hotel room to attract foreign money.

This was “my” station when I first arrived in London 20+ years ago. I remember when Oyster readers appeared on the gates before we knew what they were for. It was (is?) a bit of a pit – cramped entry and multiple levels to navigate, but the platforms are not that far. The surrounding area has had a few remakes, but the traffic pattern is still diabolical and from most directions you will wait for a few crossing lights to access the station. I suppose letting it get on with its role as a Tube station is just not acceptable to the Developer Class?

London Transport, ever since it was founded has always used property development to fund rail services – from the oversite developments above stations to the entire Metroland housing estates — trying to develop the space above South Kensington station is how the tube station upgrades will be paid for.

Visiting London from the States right now and staying close to the South Kinsington station. Last time I was here, 18 years ago, I stayed in the same area. I’ve always wondered why this station was still open top. Thanks for providing the rather sad history of what has taken place.

All the designs look pretty poor. let’s keep South Ken as is is