Running under the road between South Kensington station and the Museums is a Victorian subway, and depending on how you look at it, it’s either longer than it was, or shorter than it should be. Today it provides a swift and weatherproof way of getting to and from the museums, but its early history is unexpectedly complicated, as the current tunnel is the second attempt to build a tunnel here.

The first attempt was in 1883, when the Metropolitan Railway announced various plans to expand its network, and included in there was plans for a “subway, tunnel or covered way (hereafter called ‘the Albert Hall subway’) extended from the South Kensington Station to Albert Hall”. More details were published in the Pall Mall Gazette[1], with a map, showing the subway running from the rear of the tube station, under the houses fronting onto Exhibition Road, and up through the Horticultural Society’s Gardens (today Imperial College) to the Royal Albert Hall.

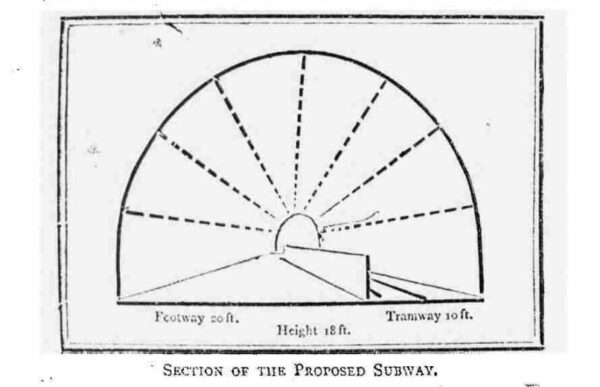

This wasn’t to be a foot tunnel though – it would have been about a third wider than the current tunnel as it would have included a rope-hauled tram as well. In addition to the tram, it would have included the new idea of the electric lightbulb to illuminate the underground world.

This was later approved in the Metropolitan Railway (Various Powers) act of 1884.

Now things get a bit complicated.

South Kensington station was owned by two railways. Using modern terminology for clarity, the Metropolitan line owned the north side (counter-clockwise trains), and the District line owned the south side (clockwise trains).

The Metropolitan line was promoting the idea of the subway as it would be able to charge a toll for using it, so this was a profit-making venture, and not wanting to miss out, the District line now proposed its own rival subway.

Yes, there were now two plans competing to build a subway.

The District line proposal was more modest though, being about half the length and lacking the tram, about a third narrower than its grander opposition’s plans. In the end, it was the District line that won the battle, with Parliament approving their scheme in June 1884[2], but granted their rival, the Metropolitan line an option to buy half the subway later if they wanted to.

The chief engineer appointed to the task of building the subway was Sir John Wolfe-Barry, who was later to go on to work on Tower Bridge, but in 1885, he was in charge of the Kensington subway project, along with the resident engineer J.S. McCleary.

Construction started on 6th January 1885[3], and the actual construction work was carried out by Messrs. Lucas and Aird.

The subway soon ran into problems though. The original plans showed the subway running under the pavement as it does today, with windows on the side facing the Natural History Museum. However, the government refused permission for the windows, which would mean they needed the same large street-level glass boxes that exist on the stretch of subway next to the tube station.

The local vestry then objected to large intrusions on the pavement and demanded that the subway run under the middle of the road. However, opposition to those plans was led by Lord Bury who worried that they would affect horses, and his campaigning saw the subway diverted back to run underneath the pavement alongside the museums, with simple glass bricks in the pavement for light.

That’s why the tunnel has the kink in it that you may have never paid any attention to – because a peer of the realm didn’t want to affect his horses.

Something else you might have overlooked as you walked over it is the flooring. Although patched and covered in places, this is still the original Wilke’s Metallic Flooring. Despite its name, it’s not actually metal — as in the sense that we think of today, but is in fact a patented concrete mix, from Portland cement mixed with blast furnace slag, potash, soda and carbonate of ammonia, and was noted for its low-slip properties when used as flooring.

The company didn’t last as long as the floors it made though – founded in 1885 it went out of business in 1891.

Back to the construction site in 1885 though, in trying to placate objectors, the District line’s solicitor, Baxters and Co, wrote to The Times on 28th January 1885 “Its construction has been urged on the company for some years, and with increased weight since the Fisheries and Health Exhibitions were opened. It has been pointed out that the crowds of people passing to and from the railway (numbering last year some four millions) ought to be considered … it has also been urged that the throng of people in Exhibition-road has caused considerable nuisance to the inhabitants and that it would be a great relief to everybody if the stream of passengers to and from the railways could be diverted underground instead of blocking the pavement”

Also, he noted that the road above would no longer be blocked by “cab-callers, hawkers, and other objectionable characters giving rise to the whistling [for cabs] and other nuisances complained of”

Construction was soon swiftly progressing, and the subway was officially opened by the Prince of Wales on 2nd May 1885[4], who gave a speech applauding the scheme, and suggesting that it should be extended up to the Albert Hall.

It opened to the public on the following Monday, with adverts promoting as a free passage in the morning of the opening day. This was a launch offer, as people would be expected to pay a penny each to use the subway afterwards. People who used the railways could have it included in their tickets.

Despite the fee to use the subway, in the first three months after it opened, some 2¼ million people used it to get to the exhibitions.

From its opening in 1885, the subway had generally only been open for major exhibitions, and the railway had charged people a penny to use the subway, with turnstiles at the entrances, although occasionally the toll was absorbed by the exhibitions and the way was opened for free. However, in December 1908, the railway company announced[5] that the subway would be permanently free of charge from later that month. This coincided with a new staircase being built close to Cromwell Road (today the entrance outside the Ismaili Centre), and the short extension of the tunnel to the current entrance next to the Science Museum, which opened in 1915.

Now this subway today includes an entrance to the V&A Museum, and that was built at the same time as the subway was constructed, but it took until 1910 for the entrance to be used, because of red tape[6].

When the subway was planned, an agreement was seemingly made that the subway would lease land from the museum site for a surface entrance building. The problem was that the subway was a private company, and the museum was part of the government’s Office of Works, and they had the opinion that governments shouldn’t lease their land to private companies. The museum was also worried about the cost of operating the additional entrance, with the extra staff needed to man it. Eventually, after years of arguments about costs and leases, a deal was struck that the subway would open its already built entrance[7] into the V&A museum, and would pay a token rent of £1 per year to the museum for the access, and finally, in 1910, the entrance opened.

It closed in 1970 due to security reasons, but was refurbished and opened again in 2004.

Another quirk of the subway is that it had used to have security in the tunnel, and about halfway down was a small hut inside the subway itself for the security guard to sit in. The security guard was described as the “loneliest man in London” as he worked Christmas Day in 1928, but the security guard said that he liked a quiet Christmas anyway, and his wife would prepare[8] a cold Christmas lunch for him.

The tunnel was closed during WWII when it was used as an air-raid shelter for 600 people, although it was only used for a year as it suffered from rats, and fixes to that problem took until after the worst of the blitz was over.

It took until 1948 for the subway to reopen to the public though, and even then the stairs[9] to the Natural History Museum didn’t reopen until 1952.

For a while, in the 1990s the subway tunnel was used to hold fashion shows during London Fashion Week.

A plan in 2005[10], which lead to the revamping of Exhibition Road was also intended to include a step-free travelator just outside the Natural History Museum down to the subway and then to South Kensington station. Depending on your perspective, it’s either regrettable that it wasn’t built, or if you’re one of the shops and cafes that would have lost a lot of passing traffic, a blessing it was never built.

More photos

Sources

1] Pall Mall Gazette – Friday 14 December 1883

2] London Evening Standard – Wednesday 25 June 1884

3] St James’s Gazette – Saturday 24 January 1885

4] West London Observer – Saturday 09 May 1885

5] London Evening Standard – Thursday 17 December 1908

6] Victoria and Albert Museum: The History of Its Building by John Physick

7] South Kensington: pedestrian subway – LCC Photograph Library

8] Dundee Evening Telegraph – Monday 24 December 1928

9] Drawing; Detail near entrance to Natural History Museum in South Kensington station subway

Very interesting. My daily commute for my first two years in London included the subway and I recall the special “metal” floor. This was the “fashion age” so also the infamous “fried eggs or melons” posters of “Trinny and Susannah” BITD – which were huge and repeated at intervals along the passage

https://likesofmeblog.com/2012/11/05/trinny-and-susannah/

We lived close to the Albert Hall and I recall when looking at the A-Z (remember that?) how close the South Ken Tube entrance was. Except that was actually the subway entrance. A drier walk at least

What was the reasoning that it would affect horses? Was it the “hollow” sound as they walked over it they were worried about?

Not specified in the documents I studied – but speculatively to do with the large vent shafts being in the road and affecting horses.

I love the map in the second last photo. Very mid-century or 1960s in style

The map must be (in the form depicted if not in origìn) 1980s as the Ismaili Centre didn’t open until 1985.

I used this tunnel almost daily throughout my student’s years in Imperial College, 1969-1971. It was at the time a rundown thing, with the walls in a pitiful state, dark and a bit dirty. Not a nice place, really, but it was useful anyway to get from the South Ken station to the College during rainy days.

Have been back to London many times since, but never re-visited this subway. Glad to know that it was later fully refurbished!