Plumstead Common is open land high up the hills overlooking the Thames, and has a very odd and very deep valley running through one side of it. How has a short, deep, valley ended up here on top of a hill?

It’s a lovely valley, exceptionally deep, with a small lake at the very bottom and glute-enhancing steps back to the top, it makes for a delightful break from the otherwise slightly bland parkland above.

Local signs and a few online reports probably copied from the signs say that it’s an ice-age relic, carved out of the ground by melting glaciers. No academic geology studies that I can find in my online searches discuss this valley, and as an explanation, it just didn’t feel right.

The last major ice sheet did indeed cover much of modern London, but just like a Black Cab, never went south of the Thames. It’s possible that there was some ice build up here, as the location would have been icy cold, but as the ice melted, why did it carve a valley only in this one location, near the top of the hills overlooking the Thames.

Just what is this deep ravine doing here?

The area is however also known for sand pits – people dug them out for construction and there are many of them in the area, indeed, much of Charlton and Blackheath is famous for them. The sands and gravels were lain down some 60 million years ago when England was under water — but now the sands are on top of the hill.

Is this valley the result of a very large sand excavation?

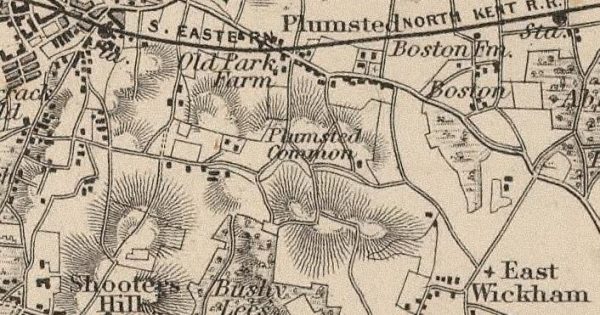

While it’s dangerous to trust old maps too much, it seemed hard to find signs of the ravine on any dating before the 1850s. This one for example shows rough indications of elevations and cuttings in the area, but nothing on the site of the ravine itself.

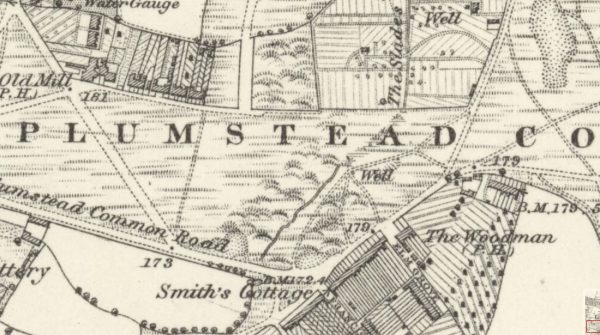

However, indications of something there started to appear by the 1870s.

Was it a new feature, or had it always been there, but not shown on maps?

Much of what is today Plumstead Common had been gifted to Queen’s College, Oxford in 1736 but was treated as common land for anyone to use for grazing, but as the area slowly built up in Victorian times, there were attempts to fence off the land.

The protests started in 1876, which at times turned violent, to protect the open land from being sold off for development were famous at the time, and lead to Plumstead Common being protected from development in an 1878 Act of Parliament that saw the government buying the land from its owners for the very generous amount of £11,000.

However, while much has been written about the workers protest to protect the Common, little is written about one particular sand mining operation.

A plot of land had been sealed off and leased to a Mr Jacobs by Queen’s College for the extracting of sand, and this was to prove highly controversial, which is not surprising considering the ongoing protests on the Common next door.

A huge protest in July 1876 against the fencing off of the Common also saw the fences around the sand pit town down.

The owner Mr Jacobs complained to the Magistrate afterwards that the fences being removed meant there was a danger of people falling some 50 feet into the pit — which gives us some indication of how substantial the mining operation was.

The protests against the sand pit operations continued through the year.

In January 1877, locals gathered in large numbers on several occasions to stop his mining works, and actually started back filling the sand pit with the material Jacob’s workers had previously dug out of the ground.

Later the same month, Mr Jacobs effectively gave up his operations saying that he needed a court order to prevent the locals from backfilling his pits. The commoners for their part said they would dispute his right to extract the gravels and sands.

The pit was later bought from Mr Jacobs under the provisions of the 1878 Act that secured the Common as open land.

The protests against the sand-pit operations suggest it must have been very large and disruptive to the local people — is the valley the result of the sand pit mines?

I was about to write that it seemed likely – until one final search of the archives just to see if there was anything else I had missed, especially as I had struggled to find any leases or papers showing the location of Mr Jacob’s excavation.

Then I found it – and oh.

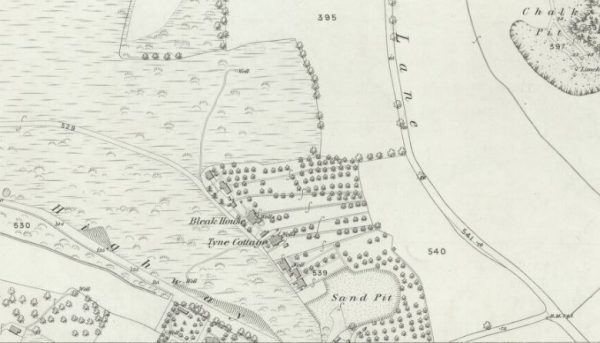

It turns out that Mr Jacob’s sandpit wasn’t that large after all, and being opposite Woolwich Cemetery, is arguably, closer to the village of East Wickham than to Plumstead. It’s likely that the ferocity of the attacks on Mr Jacobs were less to do with the size of the sand pit than the ethics of fencing off the land so no one else could excavate the site.

In fact, now I knew where it was, Jacob’s unnamed sand pit shows up clearly on this map of 1869.

A whole afternoon thinking I had solved the oddity about how a glacier carved out a valley where no glacier should have been, and I was totally wrong about my theory.

But I did learn a lot about the Plumstead riots in the process, so actually quite a fruitful afternoon, if not in the way intended.

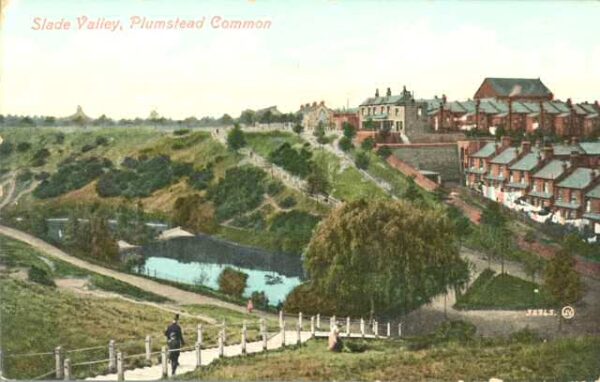

As for the valley — it looked rather nice in Victorian times, having being cleared at some point, and could have gone on to become one of those exceptionally fashionable public gardens, with terraces and a bandstand that the Victorians loved so much.

That never happened, and it was slowly returned to nature. The site actually became badly polluted over time due to run offs from the roads above, but in 1991, local campaigners were able to clear out the pollution, improve the drainage for the lake, and now it’s a wildlife haven in the midst of suburban London.

The deep sides are grassy and dry in summer, but get down deep into the valley and it’s a riot of greenery and wonderfully narrow paths that weave maze-like through the woodland to the lake hidden within.

I’m still not convinced by the glacier story.

Sources:

Luton Times and Advertiser – Saturday 08 July 1876

Woolwich Gazette – Saturday 06 January 1877

Sussex Advertiser – Wednesday 24 January 1877

Kentish Independent – Saturday 21 July 1877

Kentish Independent – Saturday 03 November 1877

Kentish Independent – Saturday 24 November 1877

The Municipal Parks, Gardens, and Open Spaces of London: Their History And Associations by John James Sexby

Excursion to Plumstead and Bostal Heath, July 1887, HM Geological Survey

Could it be a peri glacial feature caused by snow melt in a tundra environment in front of the ice sheet (which stopped at the Watford gap)? Which way does it face as I have not seen the feature but after lock down will try and visit? Note that there are several deep periglacial channels in Kent with one near Coxheath if my memory serves me well.

The high end, at Plumstead Common Road, is south west, the low end, at Roydene Road, is north east.

A straight line between those two points is 240 meters and the elevations given in Google Earth suggest the drop between them is 25 meters, although I have no means of telling if this is accurate it doesn’t seem an unreasonable figure.

I agree it could be a periglacial feature, where frozen ground is rapidly eroded by meltwater (perhaps from a lake that’s now gone). The water would presumably have been cutting down into the Thames valley. Mining is obviously possible but it’s an odd shape for that.

Water from high up on Shooters Hill has to find a natural way down to the lowest level – the river. This is one of them. It used to flood the street below so the holding pond (lake you call it) was dug to control the flow. It now takes run off from Plumstead Common Road and is next to a domestic sewer so gets mixed with sewage in high rainfall. Hence the weird we built.

The sandpits were near present Rockmount. Seriousl chalk mining around bottom of Kings Highway – hence recent sink hole

The name Slade means valley or glade in both Middle English and Old English, implying that the ravine has been a landscape feature for centuries. Given that it also faces north-east and has a watercourse, it’s more likely to be a periglacial valley instead of a sand quarry.

When I moved to Plumstead in 1990, I remember looking at a map I had bought of the area and there were caves shown on it at the top of plumstead Common. I went there eager to explore but it was all fenced off, overgrown and inaccessible. As you say, over the next few years it was tidied up and opened to the public, but the cave symbol was also removed from the maps.

Even at its greatest extent, the limit of glaciation in the last Ice Age was north of the Thames. The south side of the river was peri-glacial – defined as close to or adjacent to the edges of glacial – zone, where significant volumes of snow and ice would have been generated in winter, melting in the spring and scouring out steep V- (not U-) shaped valleys such as this one.

I grew up in Plumstead and this area was my playground. I believe that the Ravine is the dry valley of a stream. The stream in late Victorian times becoming a sewer. Look at the geology. Shooters Hill to the south has bands of differing clays and sands. It is a watershed with springs on all sides. This is not unusual in Plumstead. Travelling from East to west from the junction of Wickham Lane and Kings Highway Wickham Lane itself is a valley the small stream itself is visible behind houses to the east. Indeed it could be this stream that caused problems for the construction of Crossrail in the Abbey Wood station area Travel to the west along Plumstead Common Road and you come to Birds Nest Hollow at the junction of Adamstown Road and Blendon Terrace in the dip of the road. At the north side of the Common there is a deep valley or ravine behind the houses in Brambleberry Road and Vicarage Park. Travel further West along Plumstead Common Road which becomes Nightingale Vale a steep sided valley with Brookhill road at the bottom