In the centre of St Albans is a Cathedral, called an Abbey that’s also a church, was built by the Normans but is mostly Victorian.

With me so far?

The Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Albans sits on the presumed site of the martyrdom of a Roman soldier turned Christian convert who was executed for hiding a priest, and while at times a very important Abbey, it’s had a troubled history and at one point was nearly demolished due to neglect.

So a visit is to a building that’s a curious mix of obviously ancient, and obviously Victorian, some very modern, and yet all laid out in a Norman Abbey structure so it still retains a slightly delightfully ramshackle layout.

The original Abbey church and the monastery were laid out in the 11th-century, and although much enlarged over the years, it may have been poorly built as it suffered from a lot of structural problems, not helped by an earthquake, but by the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Abbey was in debt, the buildings decaying, and then they had their buildings looted. Being an ex-Abbey, it was transferred to the diocese of London in 1550, and although money was spent on maintenance and repairs, by the 1700s the main church building was in a very poor state, and in the 1770s, a plan to demolish it entirely and build a smaller church was nearly approved.

As is often the case, a threat to something is a spur to save it, and the next century or so saw much of what we see to do being created, or restored. Sadly, as was often the case with Victorians, what started off under George Gilbert Scott as sensitive restoration and structural repair became a conversion job under his successor Edmund Beckett, a man with as much enthusiasm for botched repairs as he had for rebuilding bits he didn’t like. A lot of his work has had to be redone in the decades since.

Something else that’s modern, and better, is a new entrance, which is how you get into the Cathedral – which is totally free to visit.

As a building, it’s big, impressive, and awesome to just amble around. There are formal tours if you want to learn loads, but sometimes its nicer to just wander around soaking up the atmosphere. A number of signs are dotted around to explain what is what, and a map turned out to be useful to realise a door leading to a chapel that seemed closed but wasn’t.

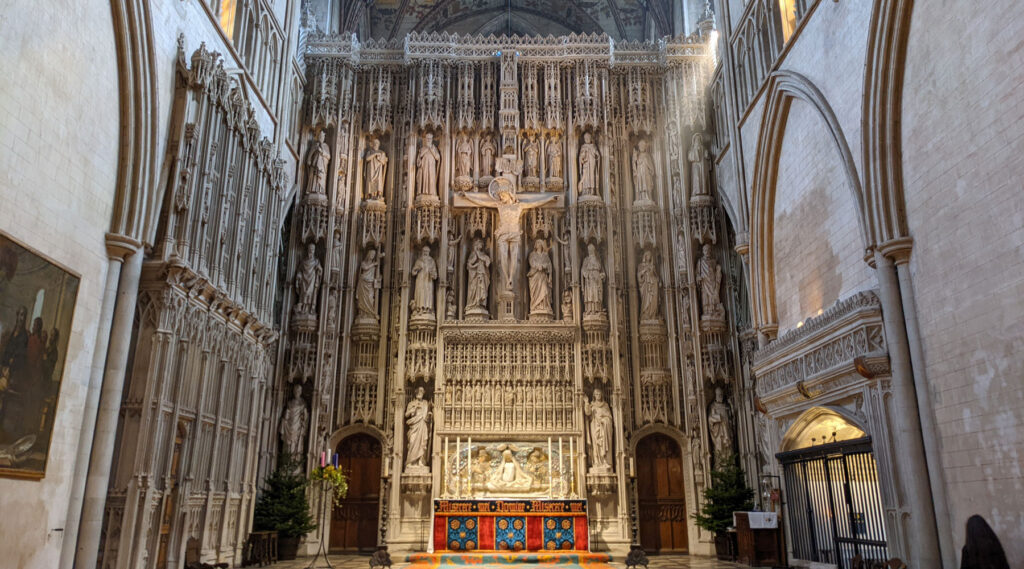

There’s a lot of shrines, including, obviously the main one to the main man, St Albans, which is hidden around the back of the main altar. The shrine dates from 1872 and includes bits from a pre Dissolution shrine that stood here, but do look at the floor, as you can just about make out the memorial chapel of Duke Humphrey of Gloucester in the basement, the only royal to be buried at St Albans Cathedral.

Recently restored, and looking it is the Shrine of St Amphibalus, which had its restoration delayed by the lockdown, and if you look very carefully, one of the carved faces is now wearing a facemask.

One of the glories of any Cathedral are their long tall naves, and his one is the longest in England. Significantly, one side has medieval wall paintings that survived puritan whitewashing. But also look at each side of the nave, the columns on one side are clearly norman arches and the other side gothic. One side of the nave fell down and had to be rebuilt, hence the change in style.

Something else to look for is the “watching loft”, the only such survivor from medieval times in England — essentially a room for Cathedral people to keep an eye on pilgrims visiting the Shrine. In essence, it’s an early CCTV room.

Do look at the tiles in the main altar area, they’re textured, which I personally haven’t seen before in a church.

It’s however, like great big old buildings, too much to take in on one visit if you want to study the history, but absolutely perfect if you want to just enjoy wandering around one of Englands oldest – if heavily modified – buildings. It’s so big, and so old, and so modified, that it’s almost like visiting half-a-dozen churches all in one place.

That’s its free to visit is remarkable. Covid restrictions notwithstanding, the Cathedral is normally open daily to just wander in and visit.

When you leave though, take a walk around the outside, if only to see the huge western entrance, which is in fact another annoyingly Victorian intervention and its dominating stone facade sits uncomfortably on the side of a mainly flint building.

There’s Norman flatpack too… the ironwork grille along the side of Alban’s shrine – just by where Duke Humfrey is buried – has little Roman numerals carved into it if you look closely. At the time, ironwork like this was beyond the British craftsmen, so it was made in France, numbered, taken to bits, shipped over and then put together again by numbers – predating IKEA by many centuries!

That would have required supervision by someone who was numerate (and probably French!). Numeracy was not a skill the average English labourer would have in Norman times.

It’s also an example of recycling, with much material, inc. Roman brick, robbed from the old city of Verulamium at the bottom of the hill.