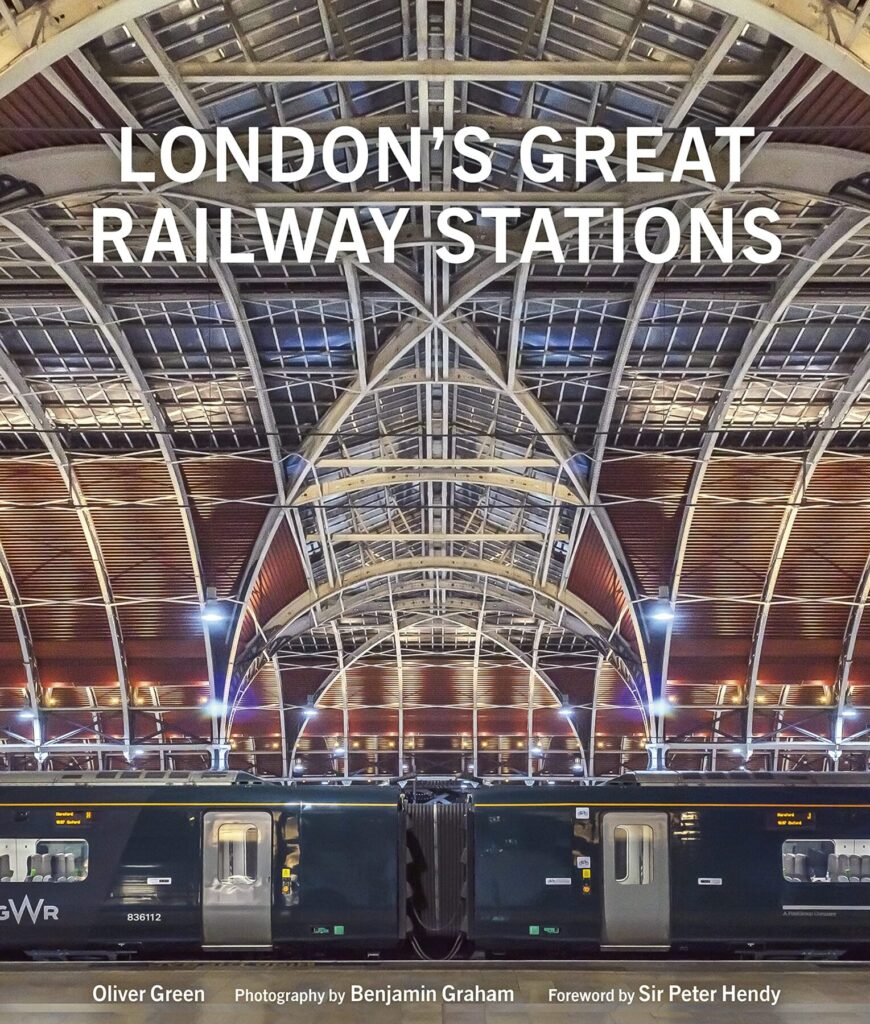

A new book rich in glorious photographs shows off London’s main railway stations, the big 13 termini that welcome people to the Capital and give a grand farewell to people heading to far-flung places.

London’s great railway termini all opened during the lifetime of Queen Victoria — from London Bridge which arrived just before she became Queen, opening in December 1836 to Marylebone which opened in March 1899, just a couple of years before Queen Victoria died — the heart of London’s railways owes their origins to the Victorians.

It’s that explosion of both brand new technology and artistry that often looked back at the past that, for the most part, still dominates the railways today — giving them a unique character.

In 1875, The Building News wrote that “railway termini and hotels are to the nineteenth century what monasteries and cathedrals were to the thirteenth century. They are truly the only representative buildings we possess”

Today, railway stations are for many of us, the largest buildings that we will ever visit, they often handle more passengers than large airports, in a fraction of the space, and with a fraction of the pollution at that. We can though become so comfortable with them, that it’s easy to become almost complacent, overly familiar, forgetting to stand back a bit and go, just wow.

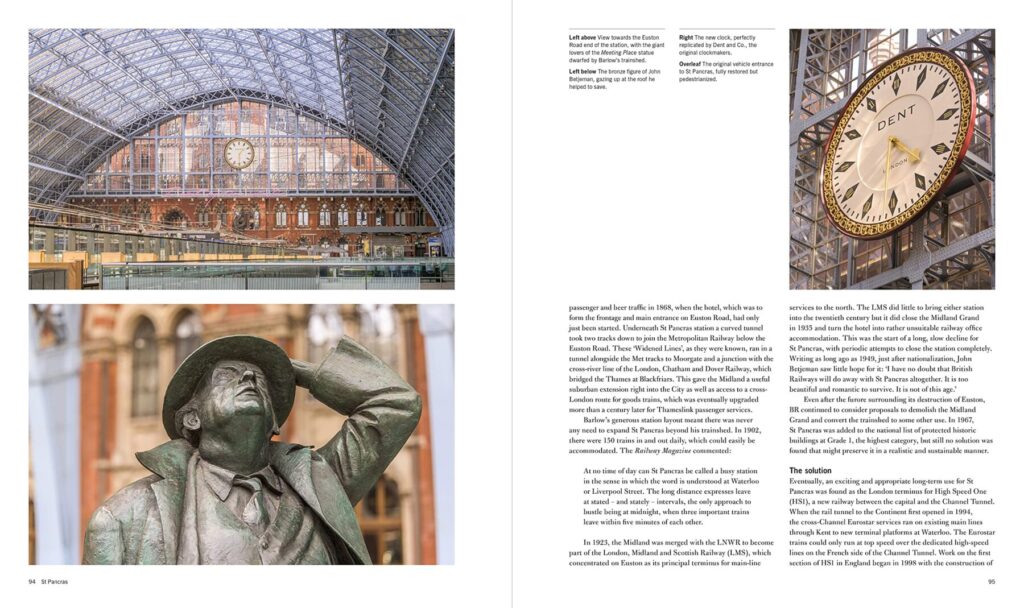

That’s what this book, with word by Oliver Green and pictures by Benjamin Graham does – it encourages us to look up and go wow.

The book takes in the great 13 stations that dominate London’s termini – yes there are technically more — but if you asked people to write a list of London’s main National Rail stations, these are the ones you’d get.

Sweeping from the grand vistas of Paddington and St Pancras to the almost villagey Marylebone and oft-overlooked Fenchurch Street, the book is mainly about the buildings, the station design and architecture, but includes notes about how the changing railways from steam to diesel to electric also left their mark on the stations.

Sometimes for the better, such as undeniably the magnificent transformation of St Pancras from a grimy sleepy backwater of a central London station into the huge hub and terminus that it is today. I recall reading a comment many years ago that when the Channel Tunnel was being planned, who would have expected the UK to have the better end of the railway.

Sometimes the changes are arguable. The author clearly does not like Euston, and in that he is in the majority opinion, even if I disagree. The grand booking hall, which today is thought of fondly and much missed, as the book notes, was at the time thought to be badly designed and totally impractical. Even if it hadn’t been in the middle of the extended railway tracks, and facing the wrong direction, had it survived, today it’d just be a branch of Wetherspoons.

London Bridge, which today looks like a radically modernised Victorian original has almost nothing of the original left — it’s all later rebuilds that has once again been rebuilt. That’s the genius of the railways, constant evolution to adapt to changing times and passenger needs.

The split personality of Victoria station is dealt with, in its many changes over the decades from being two separate stations sitting next to each other to the awkward 1980s refurbishment. John Betjeman memorably called Victoria station, “London’s most conspicuous monument to commercial rivalry”

Little old Fenchurch Street, today mainly a modern building with a Victorian facade turns out to be the first station in the country to have a bookstall in it.

Charing Cross, long a station under threat of closure, which today would seem unthinkable, was mainly derided for the railway bridge that ran across the Thames and spoiled the view.

Oliver Green says that the addition of the footbridges at the turn of the millennium improved the riverscape by hiding the railway bridge. I would argue that it accentuates it, turning an overlooked piece of background infrastructure into a landmark. Of course, the real benefit of the footbridges was to quadruple the width of space for pedestrians from an old very narrow footbridge into a boulevard, and has undoubtedly the ease of getting across the river has been a significant factor in the Southbank’s renaissance.

It’s estimated that around 8.5 million people a year now walk along a railway bridge. In a way, it echos when the Greenwich railway opened, and people would pay a penny each just to be able to walk along a footpath at the base of the wonder of the age, the railway viaducts.

Equally, the great wonder of the book is how it opens your eyes to overlook details. I find I can often judge a building not just by how it looks from afar, but how it looks up close. Is there a joy in the detailing? And thankfully, many of our grand railway stations were built at a time when the detail was King, leaving us with a rich decorative legacy to look at when catching the train.

Undeniably, the railways suffered in recent decades with cost-cutting in design and cheapness in architecture, but times are changing. Over the past couple of decades, in response to a huge surge in passengers on the railways, the stations have reawakened. Shaken of their 1970s grim appearance many have become destinations in their own right. The launch of a new Rail Alphabet 2 and regular design competitions shows there’s a pride in design again, and it shows.

Who now objects to waiting at King’s Cross or St Pancras for a train to far-flung places, or sees London Bridge as an unpleasant shabby punctuation mark in their daily commute, and just something to be dealt with as quickly as possible. Can anyone arrive at Blackfriars and not feel a twinge of excitement?

Great architecture is uplifting, and this sizeable photo rich book encourages you to look up and wonder at the railway stations. As the Building News noted that the railway stations are modern-day Cathedrals, then this book is a hymn to their design.

With a foreword by Network Rail’s Chairman, Sir Peter Hendy, London’s Great Railway Stations is available from Amazon, Foyles, Waterstones, the LT Museum, and good bookshops.

Holborn & Broad Street, gone but not forgotten.

Interesting to reread your 2013 article about Euston. Looks like Network Rail did; they have cleaned up the concourse, removed the retail huts and moved the outlets to the mezzanine floor.

Still think there is some work to be done – the pedestrian approaches in particular always feel a bit like you are working your way around the back of a building rather than arriving off Euston Road, but it’s definitely improved from what is was like a few years ago.

“We can though become so comfortable with them, that it’s easy to become almost complacent, overly familiar, forgetting to stand back a bit and go, just wow.” – So true. I need to not let this happen to me with Paddington, my London terminus. I think it is fabulous.