For nearly 1,700 years, London’s only bridge across the Thames was the famous London Bridge, until Putney Bridge was constructed in 1726. Yet London very nearly had another bridge crossing the Thames, which may have been in fact constructed, at least in part before being abandoned.

This bridge appears on one map and in some documents, and would appear to have been built during the time of Queen Elizabeth I, at around 1599.

And it wouldn’t have been in London proper as we know it today, but out in the countryside crossing the Thames, linking Blackwall with North Greenwich.

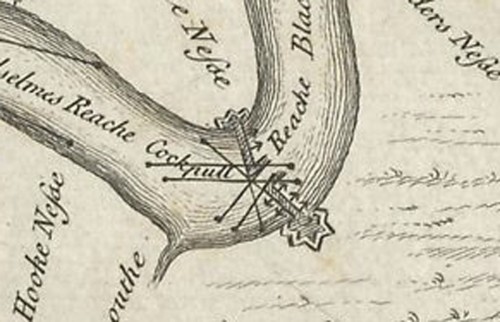

This bridge from empty fields to empty fields was not for commerce, but for military purposes, and was not originally intended to be a bridge at all. In fact, it was two mighty piers extending into the Thames with cannon mounted at the ends in the middle of the river.

A short gap lay between the piers through which friendly ships could sail, and enemies blasted to pieces.

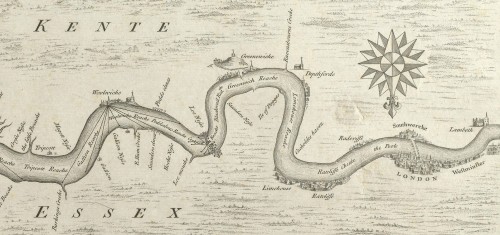

The map that reveals this lost marvel was drawn up by Robert Adams, surveyor of buildings to Queen Elizabeth I, and was designed to show “lines across the river to mark how far and from whence cannon-balls may obstruct the passage of any ship on an invasion from Tilbury to London.

An extract of the map is below:

The plan also shows the barrier at Blackwall, but while an 1881 report casts down on whether it was ever built, the report cites an unnamed document as claiming that the large piles were discovered running across the river during the laying of a new dock at Blackwall [1].

Some documentary evidence does exist elsewhere though.

For example, a letter send on the 4th August 1599 from Rowland Whyte to Sir Robert Sydney noted that “Lord Cumberland is gone to make a bridge over the the Thames, and the 6,000 men from London appointed to guard it.” [2] And again, ten days later, a second letter between the two confirmed that “A bridge is to be made over the Thames at Blackwall,” [3]

That seems to be the sole surviving record of the bridge [4], unless some reference to the alleged piles is ever uncovered in the archives.

So, letting us presume that the structure existed, as can be seen below, it would have had two forts on either side of the river, leading to two giant piers almost meeting in the middle of the river. Tantalizingly close to forming a bridge across the Thames. Incidentally, the use of the term “bridge” in the letters cited above almost certainly refer to piers, as the two words were interchangeable up until around the middle of the 18th century. So an Elizabethan bridge would have been two piers reaching to the Thames and not intended to form a link between two sides as a bridge would be expected to behave today.

But, that begs a diversion into speculation — could they have ever been linked?

Realistically, at the time of their construction, the knowledge to build a large bridge that could also be opened to allow ships to pass through simply did not exist, or at least not in a manner to make such a bridge viable. As an impediment to cargo arriving in London it would have been too great a barrier.

But, let us speculate a little, and presume that it had survived as two large piers. Come the era of the docks, it might have been seen as a convenient way of linking the two sides of the river at a time when cross-river traffic was exceptionally difficult, and with presumably existing roads leading to the two piers, much of the infrastructure would have existed on either side of the river.

The history of London’s docks could have been a very different one, thanks to defenses built to protect London from a Papist invasion.

Today though, that is still a vital river crossing, but carried out by tunnels instead of a bridge. The Elizabethans were just 300 years too early.

Notes

[1] Chronicles of Blackwall Yard, 1881 p.6:

[2] Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on the Manuscripts of Lord De L’Isle & Dudley, vol.II, 1934, p.380

[3] Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on the Manuscripts of Lord De L’Isle & Dudley, vol.II, 1934, p.383.

[4] Survey of London, vol 43-44, page 548

It seems to be a pretty eccentric design building out into the river just to support cannon. It looks rather more like a harbour mouth I wonder if it was designed to be closed with chains?

Is the image the original Elizabethan one, or a more modern interpretation of it? The lines on the map seem odd if they are meant to be trajectories from cannonballs fired from the piers; and I wonder why some have dots and some arrows?

Given the apparent capabilities of the battery at Woolwiche, the piers seem almost unnecessary.

I would never read too much into such things, but if we were to, then its notable that the arrow lines are shorter than the dot lines and could be indicative of smaller armaments.

Pity there is absolutely no evidence whatsoever for it – or indeed for the defence structures near it. I think the consensus on this drawing is that it is a speculation rather than reality.

The minute books for management of the Peninsula don’t start until the 1620s – and there is absolutely no mention of this in them, or indeed in any of the various records of riverside organisations – rate books, minutes etc. There is a record of a single roomed watch house near the tip of the Peninsula in the 17th century, and, of course, the government gunpowder testing works, at today’s Enderby Wharf, involved a number of defensive structures.

We know that some work was carried out on the Peninsula in the sixteenth century and we probably can guess the names of the drainage engineers involved. Some sluices – very recently destroyed – probably date from that period.

It is also likely that there was some sort of structure on the riverside near the Pilot Inn – but the date could be anyone’s guess – and there are new flats on the site now.

It is very likely that no archaeological evidence exists now – that site will have been used for the Blackwall Point Dry Dock in the 1870s and subsequently for gas works structures. More recently vast blocks of flats have required deep piles – and any archaeological investigation seems to be carried out very superficially and by people only interested in looking for anything pre-Roman.

(I could go on -bitterly – about the archaeologists for hours)