A hundred years ago, an unseemly spat broke out between a number of London’s museums, as the fate of one of the most significant finds of 16th and 17th-century jewellery was argued over.

What is known as the Cheapside Hoard had been discovered in 1912 by workmen demolishing an old building on, you guessed it, Cheapside, and most of the finds had found their way to an antiques dealer known as Stoney Jack.

What is known as the Cheapside Hoard had been discovered in 1912 by workmen demolishing an old building on, you guessed it, Cheapside, and most of the finds had found their way to an antiques dealer known as Stoney Jack.

Shortly after their discovery, the significance of the find became known, and the British Museum puffed up about its right to acquire the whole lot. Then the V&A piped up about how this is jewellery, and that’s their area of expertise.

Some items did end up in the British Museum, when a City of London solicitor saw them, and noted that they had been dug up in the City, and so it belonged to them — and he put in a successful claim for them to be handed to the newish Guildhall Museum, now the Museum of London.

The V&A were able to buy a few pieces, and the British Museum kept what they already grabbed.

In all this fuss, no one seemed to have given any consideration to the owners of the building the hoard was found in — the Goldsmiths Company, whose ancestors had probably made the jewels in the first place.

The squabble over who got to keep the hoard over, it was put on display in 1914 in a special exhibition However, that was the last time the hoard was seen in its entirety. Bits have been shown off occasionally, but never the entire lot.

That is about to change, as later this year, the Museum of London will put not just their collection of roughly 500 objects on display, but will also bring in the 25 items held by the other two museums.

That is about to change, as later this year, the Museum of London will put not just their collection of roughly 500 objects on display, but will also bring in the 25 items held by the other two museums.

Remembering that this was a treasure that was dug up by navvies, and then sold to an antiques dealer on the sly, it is highly likely that there are still bits of the hoard lurking in people’s attics, left over from the navvies who turned down Stoney Jack’s offers to buy them.

Thanks largely to how the hoard was dug up and dispersed, but also to the sheer uniqueness of the objects themselves, there are more questions than answers about the hoard and its origins.

A collection of jewellery that would have been worth a king’s ransom appears to have been buried in the ground in an area occupied by jewellery makers somewhere between 1640-66 and then forgotten about. It is utterly baffling as to why this would have taken place, or how the owners family could have been so utterly wiped out that no record of the hoard was passed on.

The top theory is that it was buried during the English Civil War at a time when a lot of gold was being melted down and sold to fund the war effort. But no one really knows.

It is also the uniqueness of the collection that causes problems, as there are a lot of objects there that have never been seen before. Objects of such high quality that they must have some sort of lesser predecessor, but nothing like them has been found to corroborate what the jewels were based on.

It is also the uniqueness of the collection that causes problems, as there are a lot of objects there that have never been seen before. Objects of such high quality that they must have some sort of lesser predecessor, but nothing like them has been found to corroborate what the jewels were based on.

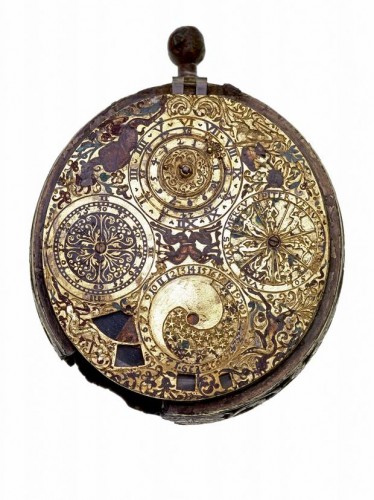

That rarity is part of what makes this probably the most significant collection of 16th-17th century jewellery in the world. Dating it is based on known fashions in jewellery design at the time, but fortunately, two objects are datable. One is a watch that was signed by the maker, and the other is probably a signet ring seal, bearing the crest of the 1st Viscount Stafford. There being just one of him, that narrowed down the date considerably.

But this isn’t just a display of English jewels, as it includes a cameo that may be of Queen Cleopatra (no, not THAT one, but her predecessor). This suggests that Tudor and Stewart merchants were collectors of antiquities.

The gems themselves, come from all over the world — from Asia and the New World. In fact, Asian gemstones were more highly prized by collectors at the time, so some stones from America may have been sent to Asia and then rebranded for sale in Europe.

And it is the gemstones that also make the hoard so special – it is an explosion of colour.

Modern eyes are more used to diamonds encrusting jewels, but that is a recent development, and in the past gemstones carried great meanings, of love or health, and were worn part as tokens between lovers, and as magical pendants to ward off illnesses.

At a time when the poor couldn’t really afford coloured dyes, a rich merchant with brightly coloured jewels would have stood out far more strikingly than we really consider today. Today with all the cheap dyes around, we seem to have fallen in love with plain white diamonds. We have reversed what the medieval person might have expected.

At a time when the poor couldn’t really afford coloured dyes, a rich merchant with brightly coloured jewels would have stood out far more strikingly than we really consider today. Today with all the cheap dyes around, we seem to have fallen in love with plain white diamonds. We have reversed what the medieval person might have expected.

Probably one of the most striking objects in the collection though is a Colombian emerald that had been carved out and an exceptionally small watch inserted within. Nothing of its sort has ever been seen before.

Sadly, over the years in the mud, the watch has fused with the emerald, and apart from x-rays, they can’t really study the watch itself.

A number of other objects are damaged, but that in turn offers a chance to see behind the gemstones at how the fittings were designed and manufactured. In fact, from a historical perspective, damaged jewels are more interesting than perfect ones.

A book is being written about the hoard by the curator, Hazel Forsyth, who has been digging through archives trying to identify who and what were involved in making the jewels, and why.

You can judge for yourself when the whole lot goes on display in October.

—

Photos from the Museum of London, who also took a few of us down into their basement this morning to have a closer look at some of the hoard being prepared by conservators for display.

Surely the stated dates include the time of the great fire; could the fire be the cause of the original loss ?

All they can say with some certainty is that it was before the fire — but almost certainly not due to the fire.

If it was buried as protection from the fire, which took 3-days to reach cheapside, then they would have gone back to recover it.

What is needed is a scenario where a vast fortune in wealth is buried, and the probably several people involved were somehow unable to return later.

That rules out the fire, but does implicate possibly the civil war.

Or – and this sounds like a great plot for a novel – A master thief who worked at the Goldsmiths stole them then hid them to retrieve later but never did? Got caught but never revealed their location?