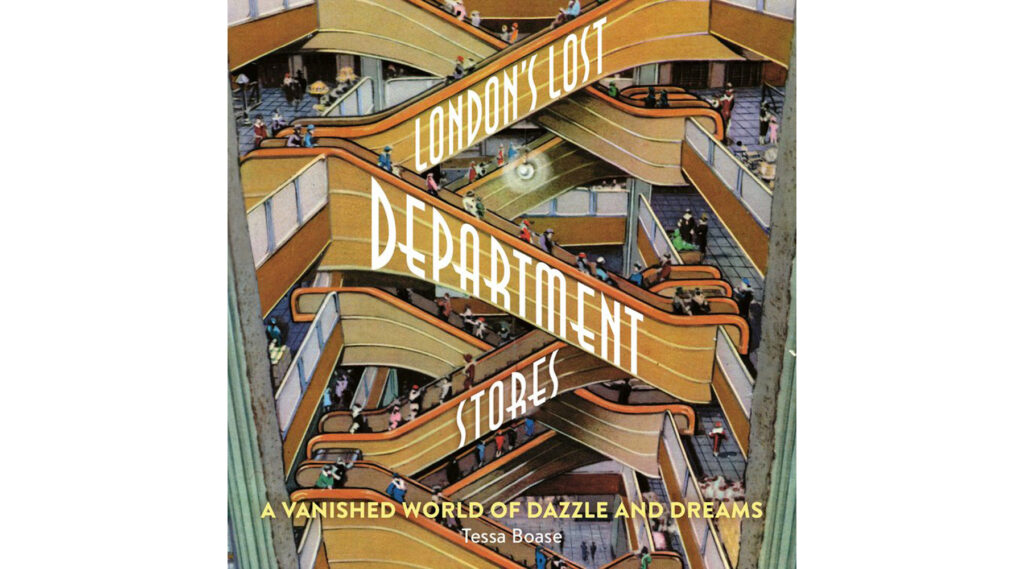

A nostalgic book has come out that takes a look at the faded memories of when shopping was glamourous and exciting, at London’s lost department stores.

There was once hardly any part of London that didn’t boast its very own department store, as a glamourous landmark on the high street offering everything from mundane household goods to clothing for a night out. Now mostly a fond memory told by the older generation, a compact but richly illustrated book tells the story of the heyday of London’s department stores.

Department stores are a form of theatre — putting on a grand appearance for the shoppers, but hidden behind the displays lay the warehouses, the narrow dirty corridors and stairs, the staff rooms and even accommodation for staff. The grand days of the department store came with both remarkable opportunities for ladies to move up the career ladder, when few other options existed, but also very Edwardian attitudes to behaviour, even down to demanding staff live in crowded shared rooms above the shops.

Of course, most department stores were also social and communal centres for the staff, and each one could, and sometimes has, filled an entire book on their own.

What the book, by Tessa Boase, does is take a brief look at 50 of the lost department stores giving a brief insight into their history and more often their quirks and innovations.

And it’s eye opening to realise not just that many areas we wouldn’t expect to have a department store certainly did, but sometimes several of them in close proximity. For example, there’s Peckham Rye with Holdrons, now finally being restored by the owner of Khan’s Bargains who has fallen in love with the building’s faded glamour, but only a few hundred yards away was Jones and Higgins with its huge clock tower that still dominates the area long after the department store closed down.

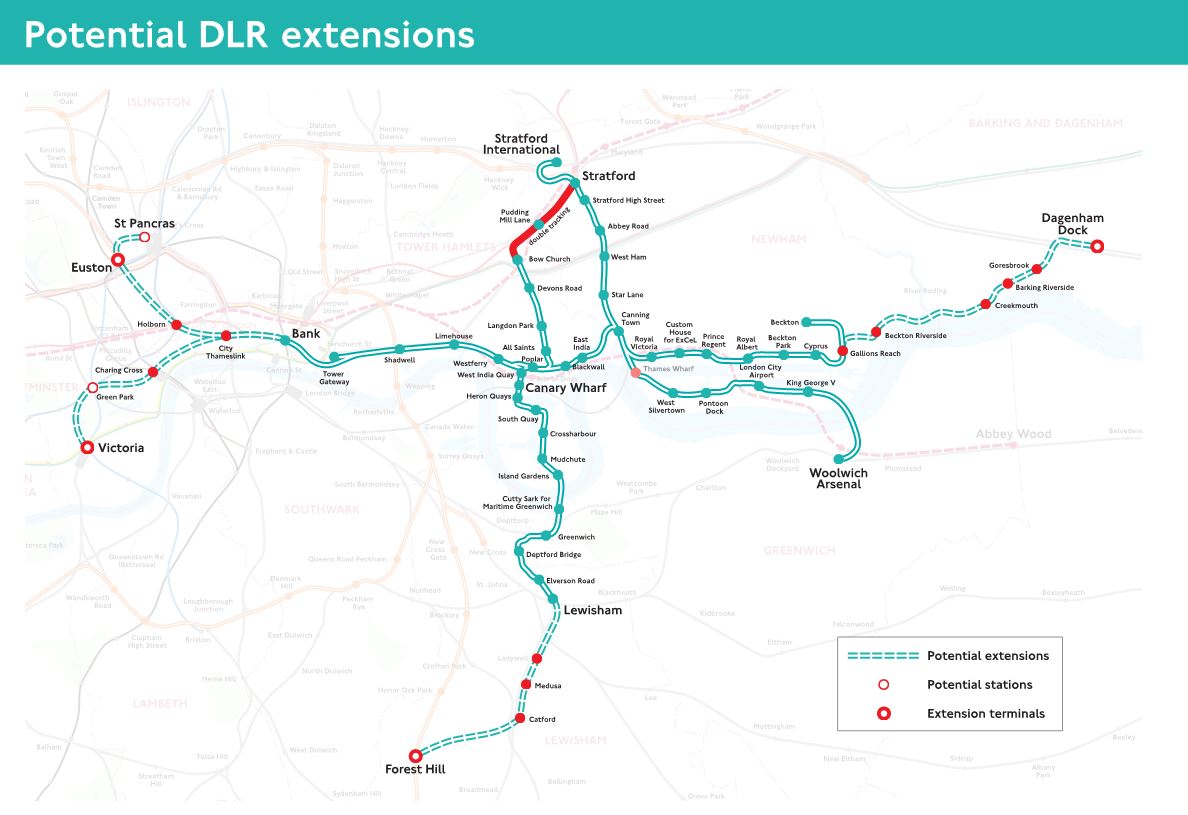

A map at the front of the book shows that there were curiously few department stores in west London, but lots in east London. Presumably going to the west end to go shopping was something the richer west London residents could afford, while local shopping dominated the east end. So while people bemoan the loss of west-end shopping, for the east Londoners, the closures of their local department stores were often closer to a family bereavement as a much loved venue finally succumbed to changing times.

And it was the east London stores that were often the most innovative in putting on a bit of a show for the customers. It was Stratford’s J R Roberts that invented the Santa’s grotto, and so popular was it that the very next year, most department stores had one, and Santa’s grotto has been a mainstay of shops and shopping centres ever since. J R Roberts closed in 1954, but the building still exists, as a giant Wilko and Poundstretcher. They don’t have a grotto.

Where the book really excels though are the interruptions to its long gazetteer of stores by looking at aspects shared by all of them – such as attitudes to staff welfare. Sometimes benevolent, but often pretty harsh, until the ladies went on strike to demand better working conditions, wages and shorter hours. In 1886, shop staff worked an average of 72 hours a week, and it was to take decades of protests to bring that down to a mere 60 hours a week. Imagine that today!

Today John Lewis is often held up as a model of good employment, but the actual John Lewis himself was a bit of a tyrant, once sacking 400 staff for going on strike for better pay. It was his son, John Spedan Lewis who set up the partnership. It’s these looks behind the customer facing theatrical glamour that really adds depth to a book that could otherwise have risked being a bit too saccharine in tone.

Many of the west-end department stores catered to the upper-class customer, with social attitudes to match, and while in a way it’s a real shame that sort of Downtown Abbey type of lifestyle has gone, it’s also a very good thing that such massive disparities in wealth and social class are a relic of the past.

Many faded over the years and closed down, but in recent years the survivors have come close to extinction as well.

It becomes very clear from reading the book that the early days of the grand department store were dominated by spectacle and shows. The grander the better. The department stores were a circus of big bold publicity stunts to lure people in.

In a way, retail is responding to the growth of online shopping by providing more experiences. Less the pile it high and sell it cheap, as online has eaten that for breakfast, and more focused on making people feel pampered and looked after in person.

The department store is returning to its roots, and only just in time.

As a book, it’s a glouriously nostalgic look at the grand old days of the grand department stores, but is in no way a hagiography of them, being very clear about the darker side of working in the department stores.

For anyone interested in history, it’s a good mix of the social and architectural history of a lost part of London. However, I suspect that if given as a Christmas present to your parents and grandparents, they will quickly look up a familiar name and sigh in delight at childhood memories of the glamour of their local department store. And spend the entire Christmas lunch talking about it.

The book, London’s Lost Department Stores is by Tessa Boase and is available from Amazon, Foyles, Waterstones, book stores or direct from the publisher, Safe Haven.

Department store trivia – all in the book

- In 1937, Bentalls of Kingston lured crowds to its glass atrium with a female stunt diver.

- In 1900, some 250,000 women worked in shops. By 1965, the number was over a million: a fifth of Britain’s female workforce.

- Shoplifting, or ‘kleptomania’, was thought to be triggered by female hormones.

- A pair of Jones Bros pyjamas, bought on the Holloway Road in 1909, were used as critical evidence in the sensational Dr Crippen murder trial.

- In 1952 John Barnes of Finchley Road opened London’s first self-service food hall.

- In 1930, Chiesmans of Lewisham thrilled shoppers with ‘Vixen the Untamed Lioness.’

- When Simpson Piccadilly opened in 1936, it featured a floor of tailors, cutters and pressers working away in full view of customers.

- The first elevator was installed at the Army & Navy in 1880. Barber’s of Fulham didn’t get around to installing one until 1988 – six years before it closed.

- Harrison Gibson of Ilford burned down to the ground not once, but twice: 1924 and 1959. Bromley’s Harrison Gibson also burned down in 1968.

- In 1864 Lady Florence Paget gave her fiancé the slip at Marshall & Snelgrove, entering by the Oxford Street entrance, and exiting by Vere Street.

- Joanna Lumley worked as a ‘house model’ for Debenham & Freebody in 1966 on £8 a week

- When the Galeries Lafayette opened on Regent Street in 1920, its Pierre Imans wax models looked so real it was thought to be haunted.

- Peter Robinson was the last department store to have staff ‘living in’ until 1912.

” it’s also a very good thing that such massive disparities in wealth and social class are a relic of the past.”

Social class perhaps, wealth not so. London is full of wealth inequality.

Not on the scale it was in Edwardian times that was the heyday of the department stores – check out how the Gini Coefficient has changed over the past century or so, and you see that inequality was far worse in the 1930s than it is today.

West London had several department stores. Tudor Williams in New Malden only closed in 2019 but Ely’s in Wimbledon is still going strong.

I’d argue Wimbledon and New Malden both are more affiliated with ‘South’ than ‘West’