London’s famous three – Piccadilly Circus, Oxford Circus, Regent’s Circus. Hang on, Regent’s Circus? Yes, the huge circle at the top of Regent Street lined with expensive houses. Haven’t you seen it?

No, and neither has anyone else, other than people looking at old maps who occasionally see it proudly appearing when optimistic map makers included a planned development that never happened.

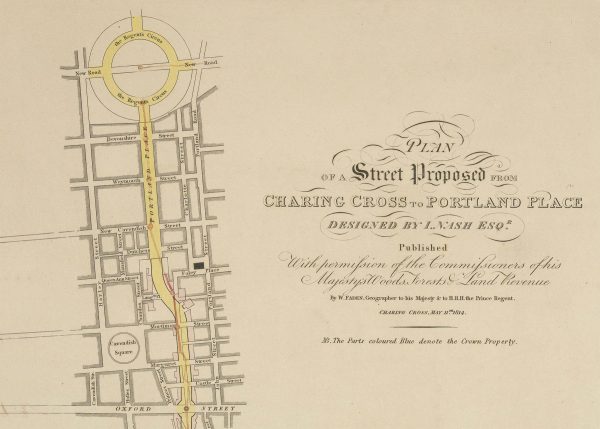

John Nash’s famous scheme to develop a new road linking Marylebone Park down to Whitehall, which was to become the Regent Street we know today, was supposed to include three large junctions, of which Regent Circus was to be the largest and most impressive of them all.

The need for the circus was caused by the north-south Regent Street intersecting with three major east-west roads, and Nash felt a simple crossroads lacked the dignity that a circular space lined with colonnades would create.

However, due to space constraints, what are today Piccadilly Circus and Oxford Circus are smaller than originally planned, and lacked the colonnades he wanted. However, to the north lay more open land and space to create the perfect junction that Nash originally wanted.

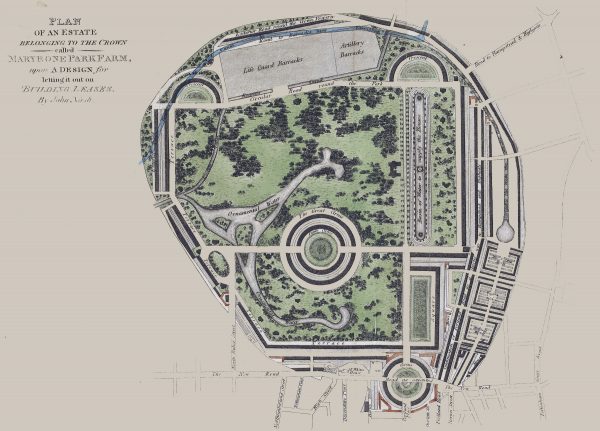

And it would have been huge — at around 700 feet in diameter, if it were at Oxford Circus, it would swallow up many of the shops between the John Lewis and Liberty department stores.

The site of the Regent Circus was just to the south of Regent’s Park on land which was farms leased by the Crown, but the leases expired in 1811 allowing for the long desired redevelopment.

The approach to the grand circus was, thanks to a legal quirk, equally grand. If you’ve walked north along Regent Street past the BBC, you come to Portland Place, a very wide grand street. Its expansive width being thanks to legal judgement of 1767 that the view northwards from the (now demolished) Foley House must remain unobstructed.

The original plan was for Portland Place to run in a straight line down to Oxford Circus, but a dispute between John Nash and Sir James Langham who now owned the land saw the kink added outside the BBC.

But back to Regent Circus, in March 1812, the developer, Charles Mayor won the £300,000 contract to build the circus, which was to be lined with stone-clad buildings and a “collonade of coupled columns surrounded by a balustrade”

Together they widened the inside of the circus, to create houses with frontages of 100 feet wide each, although at the cost of less space at the back of each house, and the plans called for the entire circus to be completed by the end of 1816.

Here it’s important to note that the contract stipulated that the houses on the southern side of the circus were to be completed first — and this will prove to be significant.

By August 1813, leases were being issued to plots of land around the southern side, as construction of the core structure of the houses was now underway. However, it was also the time of the Napoleonic Wars, and as is often the case during war, people stop spending money.

Charles Mayor slowed his construction as the hoped for leases proved slower to get signed as expected, and this caused concerns to John Nash who needed the grand circus to encourage the correct sort of people to live in the area, and in turn support the development of fine houses elsewhere on the development.

By April the following year (1814), work had completely stopped, and the developer was seeking a loan to complete the site. The Crown was otherwise occupied with war, and declined to lend the money to complete the site.

In 1815, Charles Mayor was taken to Fleet Prison as a bankrupt.

Attempts to sell off the half-built houses in the post-war years proved even harder as they slowly decayed in the British weather, but by 1822, the entire southern half of the circus was deemed to have been completed, albeit in a piecemeal fashion by a number of different owners.

Despite that, the scale of the Regent Circus is clear to see in a painting by Rudolph Ackermann made in 1822.

But this was only half of the planned circus, and following the problems with the southern half, even John Nash realised that he would never realise his dream and cancelled the plans to complete the circle.

The completed semi-circle was renamed as Park Crescent, and it remains there today, but the great vista’s that were planned have also been lost as the inner circle was turned into a private garden.

Today, it’s just a posh curved road, and not the mighty open circus that was planned. And basically, it’s all Napoleon’s fault.

More recently:

What we see as the ornate Georgian crescent is in fact, a fake — damaged badly during WW2. When rebuilding works were carried out in the 1950-60s, it was found that the buildings were in such poor condition that renovation was almost impossible. In the end, they were demolished, and similar replicas installed instead.

Sometimes, London’s 1960s architecture does work.

The loss of the Georgian originals in the 1960s is also why today, you can see a vast building site on the crescent, as the 1960s facades are swept away by yet another developer, who aims to return the site to something closer to the original collection of grand houses.

And finally:

As it happens, there were plans for a fourth circus as part of the scheme, and it was laid out, but not built. It’s the Inner Circle of Regent’s Park itself, which was supposed to have two concentric rings of housing within it, but in the end just a few houses were built and it remains purely a decorative ring road within the park.

Sources: