The Houses of Parliament, that impressive confection of gothic architecture should look a lot plainer — in fact it should be Georgian in style — had plans to erect a new building in the 1730s been carried out.

Newly enthroned monarch, George II and the UK’s first Prime Minister, Robert Walpole wanted to sweep away the tired old medieval cluster of buildings next to the Thames and usher in a new age fit for the Georgian monarchs and a stronger more assertive Parliament.

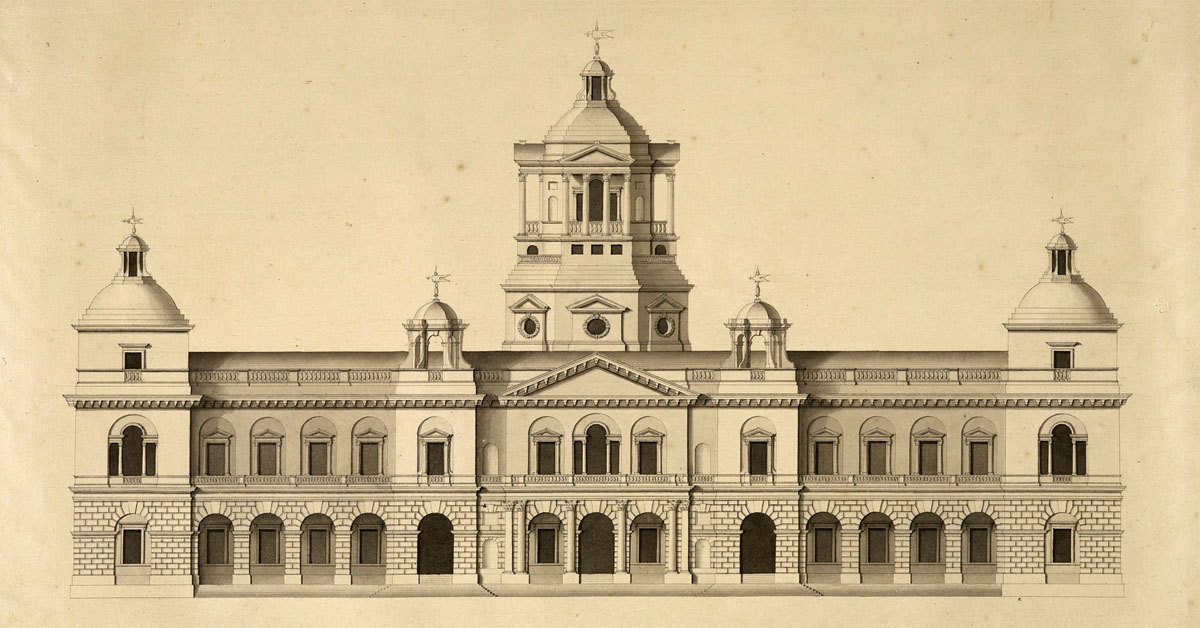

Thus, in 1733 the architect, William Kent was commissioned to design an “edifice that may be made use of for the Reception of the Parliament”, and what an edifice it would have been.

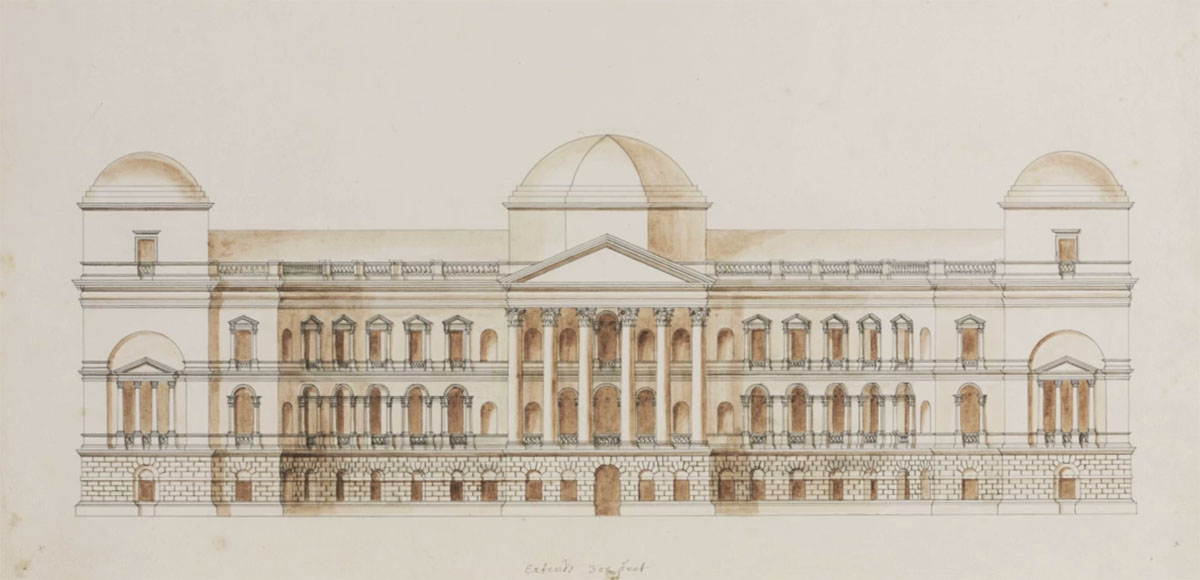

A massive building some 444 foot long facing onto the river with a largely face-on design that would have created a mighty wall of white marble pocketed with windows.

As was the type of the Palladian style of architecture of the era, it would have looked more like a grand house than a Parliament, albeit on a considerably larger scale.

A number of towers on top would have provided ventilation to the centre, and imposed Parliament onto the skyline of London.

However, it was within that the greatest development would have occurred. At the time, the notion of political parties as we understand them today was still in its infancy, so the House of Commons would have been in the round, more like an amphitheatre, as opposed to the current design of two sides facing each other.

The amphitheatre design is one which is more popular with modern Parliaments, and the UK only got its more confrontational design by accident — it’s how St Stephen’s Chapel was laid out when the Commons sat there.

How different would our political system be if the circular layout had delayed the emergence of party politics?

Kent submitted a number of plans over the next decade, each progressively plainer to reflect changing tastes, but by the 1740s, the government was short of cash, and short of political authority. With the downfall of the Prime Minister, the plans were quietly shelved.

The old cluster of buildings carried on being used, until they in turn finally burned down in 1834.

Thanks to a quirk of history, the Thames is lined not with Portland stone, but brown sandstone. A gothic design that later came to symbolise everything that is British about the British to foreigners.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of the failure to build Kent’s commission, as images of Parliaments dominate the definition of politics in every country. The UK would see the world of politics dominated by sombre stone and serious facades.

As it is, every image we see of political intrigue now, is gothic.

And would the opening credits of House of Cards with its flyover of Big Ben have been as dramatic?

You might well think that, but I of course, couldn’t possibly comment.

Sources:

William Kent – Designing Georgian Britain

V&A Museum – William Kent: Designing Georgian Britain

Find more “unbuilt London” articles here

1940s???

What about the 1940s?

“Kent submitted a number of plans over the next decade, each progressively plainer to reflect changing tastes, but by the 1940s, the government was short of cash,”

Ahh,

Thanks.

What would Budaapest’s riverside look like if they hadn’t had London’s parliament buildings to imitate? (With added dome.)

The Palace of Westminster was truly a product of its time: the shifting tastes of the 19th century would have made it impossible to build something like it at any other period. The construction of the new Palace took so long, in fact, that its style was considered outdated before the thing was even finished; had the Houses of Parliament burnt down twenty years later, it is conceivable that their replacement would be Gothic of a more complex and decorated style. It wouldn’t be out of place to imagine, perhaps, the plain (and partly for this reason, iconic) lines of Big Ben replaced by the more elaborate profile of the clock tower of St Pancras Station.

On the other hand, had the fire occurred just ten or twenty years earlier, the continued dominance of Classicism would have ensured that the new structure would conform to that style, and the final result would resemble, to some extent, what we see above. (Though it cannot be taken for granted that its location would remain the same; the Westminster site was considered cramped and unhygienic, and alternatives were actually considered in 1835.)

The matter of size is also important. One can see that Kent’s planned building would be considerably smaller than what was eventually built. This makes sense, because any new seat of the legislature would reflect the needs of that institution as perceived at the time of its construction, and Parliament before the Great Reform Act was one of part-time legislators meeting for a few months and then returning to their estates in the country. I am not saying this changed overnight, being the gradual process that it was. But the role and workload of the House of Commons increased considerably in the course of the 19th century (just think of all the committees needed to examine bills during the Railway Mania of the 1840s) and MPs began to take their duties more seriously. The facilities offered by a Georgian building would definitely prove inadequate far more quickly than its builders would have imagined.

Its Victorian counterpart also presented the same problem, again sooner than expected, because no provision for MPs’ offices had been made. In this case, however, they had a very large building to adapt, and by infilling courtyards and converting officials’ residences they made do until the 1970s, when they finally spilled out of the Palace into the vacated headquarters of Scotland Yard. But such a large Senate House (as they might have liked to call the seat of Parliament then) wouldn’t—and indeed, probably couldn’t—have been constructed in the 18th century, and one can only wonder about what would happen once the two Houses found themselves in need of much more space than was available. Would this building also be demolished and replaced by something larger, and possibly quite different? Or merely extended, perhaps to the detriment of its architectural quality? Would a 19th-century version of the Parliamentary Estate be the result, a cluster of office buildings springing up around Kent’s edifice? Or maybe the two Houses would move to another location altogether, leaving the classical design above for some other use, to share the fate of Dublin’s earlier purpose-built parliament building?

We can never know, of course, but it is an interesting question. The fate of this unbuilt monument would be far from secure under these circumstances.