In an age where people were thinking the future of mankind was more leisure and less work, thoughts turned to how such pleasure was to be enjoyed. One of the more daring proposals was palace of fun, to be built in the East End of London.

In the late 1950s to early 1960s, there was much talk about an impending arrival of a society with ever increasing amounts of leisure time.

In 1959, the Labour Party wrote that “in a properly planned society, it is possible to guarantee full employment; and, as automation spreads, it will also become possible, while maintaining full employment, steadily to lessen the number of hours that most people have to work.”

Meanwhile, New Statesman agonised that “Leisure is still confused with idleness – and sin.”

Providing facilities for people to be active in their leisure was seen as an important part of post-war reconstruction.

So along came the Fun Arcade.

Originally an idea by the avant-garde theatre producer Joan Littlewood, who wanted to expand her theatrical work into a new form of architecture where the barriers between audience and actors was broken down.

Writing in New Scientist, Littlewood said that “the essence of the place will be informality – nothing obligatory – anything goes. There will be no permanent structures. Nothing is to last more than ten years, some things not even ten days”

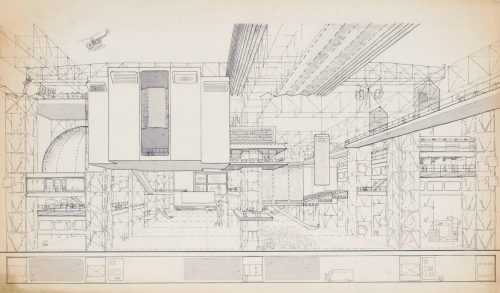

This was the genius of the building, it was to be dynamic and ever changing. A basic shell to provide a scaffold within which rooms and spaces could be created and destroyed as needed.

However, she was not an architect, but was fortunate to meet the young architect Cedric Price who grasped the concept and ran with it.

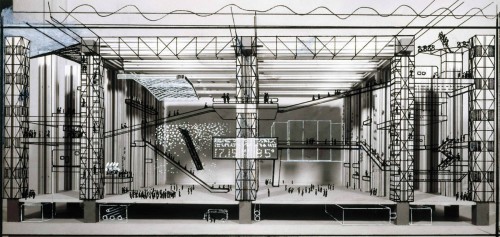

He came up with the notion of an improvisational architecture, which would be in a constant state of construction, dismantling, and reassembly. He thought of the building as a skeletal framework, within which enclosures such as theatres, cinemas, restaurants, workshops, rally areas, can be assembled, moved, re-arranged and scrapped continuously.

Structural engineer Frank Newby assisted on the design, which ended up with fourteen towers, forming two 60 feet wide aisles which flanked a 120-feet wide central bay.

The towers were for services, leaving the central voids empty to be filled with the temporary walls and floors they envisioned.

A couple of massive gantry cranes would run along the roof line to assist in the constant redesign of the interior space, so that shifting walls would be easier and there would be fewer barriers to change.

The concept gained political support from the likes of Tony Benn, and cultural support from cybernetician Gordon Pask and journalist Malcolm Muggeridge.

Pask’s involvement was to see the concept evolve somewhat though, with the introduction of computer control over how the spaces were to be used, with then fanciful notions of monitoring usage and adapting the spaces based on how individuals behave.

Today that vision exists as a standard function of the internet which is often customised to the user, but at the time the notion was seen as otherworldly, and slightly attempting to reduce people to cogs in a giant machine. Less cogs in labour than laboured leisure.

However, well meaning words and drawings do not make for a final product, and despite many attempts to find a building site, with two coming close in the Isle of Dogs and Lee Valley, the Fun Palace remained nothing more than a high ideal.

Eventually, in 1975, Price declared the project dead.

The concept was to influence other architects though, although at a more realistic level — and one of the most famous derivatives was eventually built. The Pompidou Centre in Paris, designed in 1971 and opened in 1977.

And today, we work ever harder and longer. The notion of a leisure filled society never happened, because technology changes made it possible to work fewer hours, but also offered more baubles to buy, which means working longer to afford them.

Sources:

Fun Palace document folio, Cedric Price Archives.

New Scientist, May 1964, A Laboratory of Fun

The City and the Architecture of Change: The Work and Radical Visions of Cedric Price

Labour Party Publications, Leisure for Living, 1959

The concept sounds like an exhibition centre. Your description pretty much matches the function of the Excel Centre. What comes around goes around…

“sounds like an exhibition centre” Indeed! Also made me think of the flexibility of Tate Modern.